KATHMANDU: Bhim Udas was born in Taksar Bazaar, Bhojpur—a historic town where Prithvi Narayan Shah unified Nepal in 1872 B.S., and later, King Girban Yuddha Bikram Shah established the Taksar Mint, producing one- and two-paise coins.

With a legacy spanning over two centuries, Taksar is deeply rooted in Nepal’s early statecraft and trade.

Udas completed his secondary education at Bidyodaya Secondary School and pursued higher studies at Mahendra Morang College in Biratnagar.

Initially drawn to teaching, literature, and journalism, he eventually transitioned into international diplomacy, reshaping his professional identity.

After working briefly at Kulekhani Hydropower, Udas joined the United Nations, where he served for three decades, gaining firsthand experience with global humanitarian crises—from famine in Africa to conflict in the Middle East, and geopolitical tensions across Europe and America.

Following his retirement from the UN, Udas was appointed Nepal’s ambassador to Myanmar. His tenure gave him a unique perspective on the deep-rooted presence of Nepalis in Myanmar and the complex socio-political landscape there.

In his own words, Udas shares that Nepalis have played a significant role in bridging civilizations between Nepal and Burma.

Many of those who first migrated from Nepal via India to Myanmar were fleeing feudal oppression and seeking livelihoods. Some traveled to Assam to work in coal mines before moving onward to Myanmar through Manipur.

During the British colonial period, India and Burma were a single administrative entity.

Migrants, including Nepalis, could settle freely. They cleared forests and converted land into farmland, which they could use without ownership documents—only needing to pay taxes on the produce.

Indians enjoyed similar privileges, but Nepalis often sought out hilly regions for settlement.

Udas recounts a town called Myitkyina—now the capital of Kachin State—which once earned the nickname “Little Nepal” due to its large Nepali population.

There, Nepalis engaged in agriculture and livestock farming. Some cultivated hundreds of bighas of land.

During that time, Myanmar also had deposits of gold. Locals could find small nuggets by sifting sand from rivers.

Later, the discovery of ruby mines attracted both Chinese and Nepali interest. Although the Chinese attempted to dominate the sector, Nepalis—particularly the Gorkhas—resisted fiercely, earning the respect of many. Over time, however, these once-thriving mines dwindled in significance.

Some Nepalis had arrived during British rule as part of the military. The Fourth Gurkha Rifles, in particular, had a strong presence in Burma and remained active even after independence.

During the era of Aung San Suu Kyi, six soldiers, including one Nepali, were awarded the Victoria Cross. Their names are inscribed in gold, and statues honor their bravery.

According to Udas, the people of Myanmar view Nepal through three powerful symbols: Lumbini, Gorkhas, and Everest. This trinity symbolizes their deep admiration and respect for the Nepali identity.

However, Udas also highlighted a growing concern—due to lack of opportunities and systemic neglect, many Nepalis in Myanmar have converted to Islam in recent years, simply to access jobs or integrate into the majority population.

Despite these hardships, Nepalis in Myanmar have preserved much of their heritage. Their dialect retains the tone of old Nepali, reflecting the language spoken generations ago.

In this distant land, the legacy of Nepali culture lives on—even as it grapples with modern challenges.

Outside of Nepal and India, Myanmar is perhaps the only country where the Nepali language is still actively spoken and Nepali literature continues to be written.

The Nepali-speaking community there has shown a strong interest in literature and cultural preservation.

During the military regime, however, literary and cultural materials from Nepal were strictly prohibited. Even simple items like Nepali calendars were unavailable.

People would eagerly await the arrival of a calendar from Nepal—it would be circulated throughout the community. These days, around 50 calendars are ordered through the Nepali embassy and distributed across different regions annually.

Despite this cultural resilience, the community has faced challenges. In recent years, a significant number of Nepalis in Myanmar have converted to Christianity.

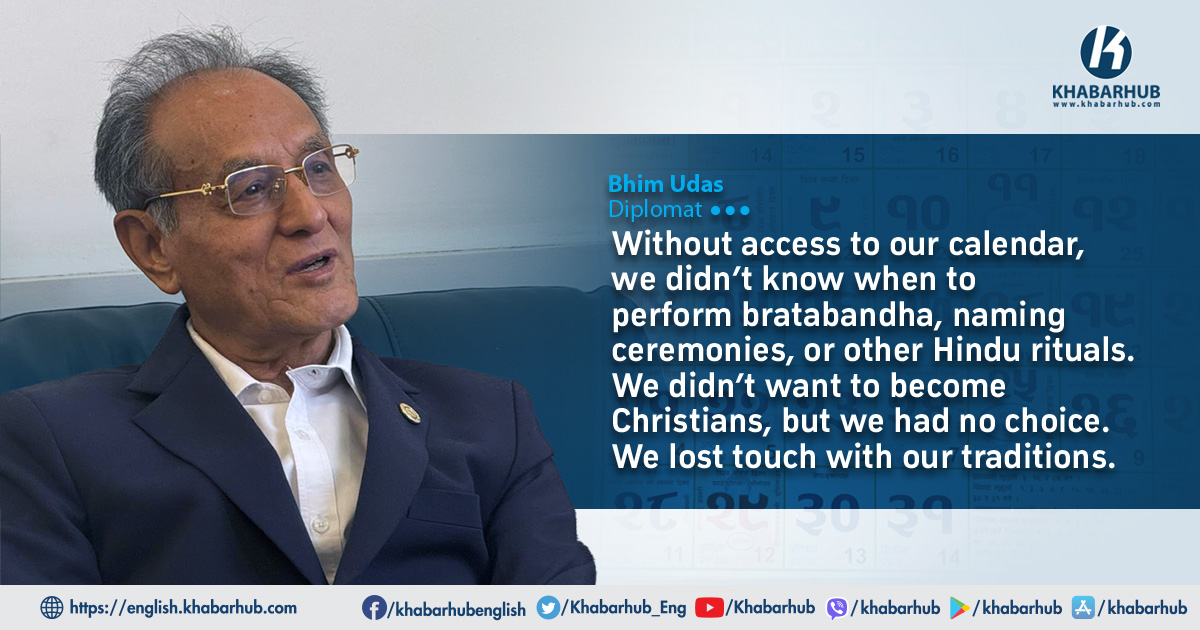

When I visited Nepali-speaking areas and asked why they converted, they explained: “Without access to our calendar, we didn’t know when to perform bratabandha, naming ceremonies, or other Hindu rituals. We didn’t want to become Christians, but we had no choice. We lost touch with our traditions.”

There are many heartening yet curious expressions of “Nepaliness” in Myanmar. For example, when I visited a local market, I saw iskus (chayote), a vegetable common in Nepal. The locals called it “Gorkha Di.”

When I asked why, they said, “Our ancestors brought the seeds from Nepal.” Many agricultural practices, such as producing milk, ghee, and sweets, were introduced to Myanmar by Nepalis.

Some schools in Myanmar even offer Sanskrit education, from primary level up to Shastri.

Around 50 students graduate annually, many of whom go on to become priests—not just in Nepali-built temples but also in Indian temples and even those in Thailand.

There used to be about 500,000 Nepali speakers in Myanmar; that number has now dwindled to roughly 250,000. Nevertheless, the community has built over 320 temples across the country, with names like Ram Mandir and Pashupati Mandir. The latter is designed to resemble Nepal’s own Pashupatinath Temple.

“We may not be able to visit Nepal,” locals told me, “but we’ve built our own Pashupati here. It is our way of staying connected to the land of our ancestors.”

I once visited such a temple during the military regime. As word spread that Nepalis had arrived, people gathered. When they found out we were from Nepal, they held our hands and bowed, saying, “You’ve come from Pashupati, from our ancestral land. By touching your hands, we feel sanctified.” It was a deeply emotional moment—we were moved to tears.

The community still wears traditional attire at weddings: gunyu cholo, daura suruwal, Nepali topi, and even khukuri.

They also celebrate Deusi every year, and in the same way they’ve done for the past 150 years. While Nepal has evolved with modernity, their traditions remain intact.

Though Nepalis in Myanmar face some discrimination compared to the native population, it is less severe than what Indians or Chinese experience.

Nepalis are allowed to join the army, and a few have even reached the rank of colonel, though most aren’t promoted beyond major.

I once met the Home Minister of Myanmar, a Lieutenant General, who told me, “We want more Nepalis in the army, but fewer are joining these days.”

When I subtly raised the issue of discrimination—why qualified Nepalis weren’t being promoted—he said nothing. As I was leaving, his father remarked that I had spoken too bluntly.

Economic ties between Nepal and Myanmar remain weak. Despite Myanmar being rich in natural resources like gold, rubies, and sapphires, bilateral and multilateral relations have stagnated due to the country’s prolonged military rule.

Travel and exchanges remain limited under such governance, hindering closer cooperation.

During my tenure in Myanmar, a direct trade relationship between Nepal and Myanmar had finally begun to take shape.

At the time, the army general also served as the country’s Vice President, and there were active discussions between him and various business organizations about initiating bilateral trade with Nepal.

Interestingly, many of the lentils we now consume in Nepal—labeled as Indian imports—actually originate from Myanmar.

Each year, India imports 1.5 to 2 million tons of pulses from Myanmar. During my time there, efforts were made to import these pulses directly to Nepal.

I repeatedly urged the then-president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI) to engage.

Business organizations in Myanmar, including their chamber counterparts, had even formally requested that Nepal send representatives. Unfortunately, no one from Nepal responded or visited.

Instead, I facilitated a delegation from Myanmar to visit Nepal. A group of ten delegates arrived a few weeks before the president’s visit.

Later, during Nepal’s second investment conference, I brought another delegation of 26 people, including a government minister.

Following the conference, discussions were held between the Myanmar delegation and Nepali business leaders about importing pulses directly from Myanmar.

The plan was to transport the goods from Rangoon to Visakhapatnam in India and then by train to the dry port in Birgunj, bypassing the need for Indian intermediaries.

That very year, Nepal imported approximately 80,000 metric tons of various pulses through this route—marking the beginning of direct Myanmar-Nepal trade in this sector.

There is immense potential for expanding bilateral trade with Myanmar. For example, we import significant quantities of marine products from Thailand—many of which originally come from Myanmar. Myanmar is also rich in teak wood, a resource Nepal barely produces.

During my tenure, some handmade Nepali goods, including pashmina, were introduced to the Myanmar market.

The response was overwhelmingly positive—people appreciated them simply because they were labeled as Nepali products.

There is also strong investment potential from the Nepali diaspora in Myanmar. Many of them are well-established and wealthy.

Some have even expressed interest in investing in Nepal. One group involved in the ruby trade conducted a geological study of a hill in Gulmi, believing it could contain ruby deposits.

They were willing to use their expertise to mine there. However, both local communities and government authorities refused to allow them to operate.

Their sentiment was clear: “We have years of experience working in this field. If Nepal would just invite us and allow us to contribute, we would gladly do it for our homeland. But we’re not allowed.”

Sadly, a few have already lost their investments due to bureaucratic hurdles.

They’ve been told that investing the wealth they earned abroad into Nepal is risky, and in many cases, it has led to financial loss. As a result, potential investors remain hesitant—despite their emotional and cultural ties to Nepal.

Comment