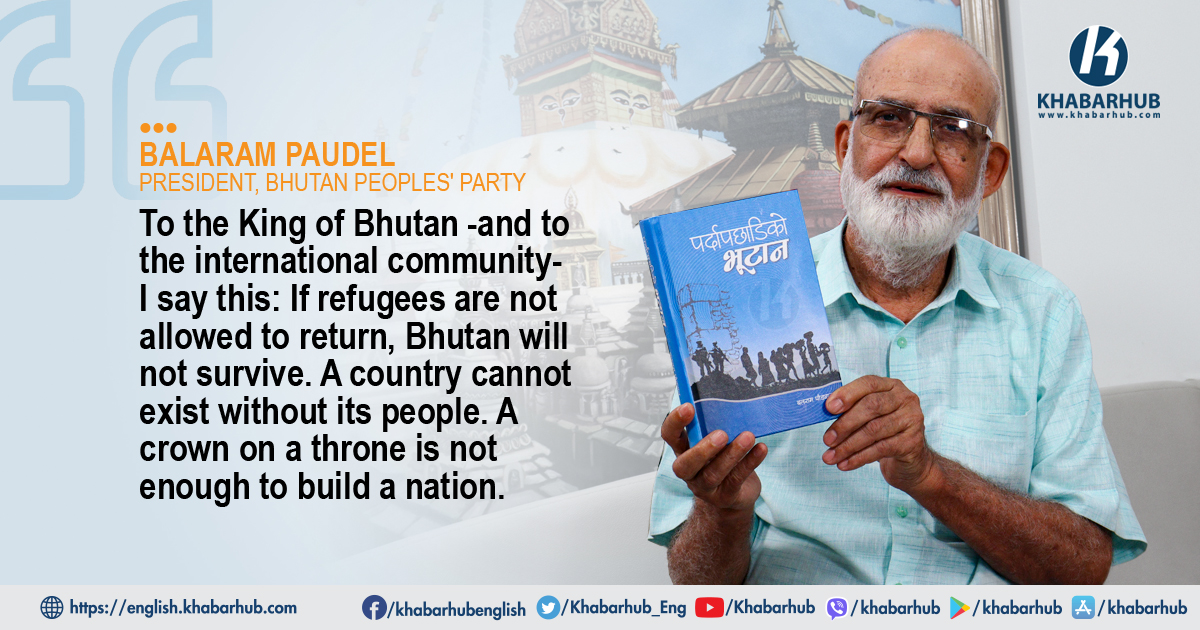

KATHMANDU: Balaram Paudel, President of the Bhutan People’s Party (BPP), first published his book Bhutan: Past and Present in 2001. Now, more than two decades later, he has released a new 394-page book titled ‘Pardaa Pachhaadi Ko Bhutan‘ (Bhutan Behind the Curtain), published simultaneously in both Nepali and English.

After three unsuccessful repatriation movements, Paudel believes this new book could serve as the catalyst for a “fourth movement” to return exiled Bhutanese to their homeland.

Currently living in Nepal as an asylee, Paudel described the situation in Bhutan as increasingly fragile, warning that even the country’s territorial boundaries appear to be shrinking.

He said his final wish is to die on Bhutanese soil—and if that is not possible, he has asked his family to take his ashes back to Bhutan and scatter them there.

He also raised concerns that without concrete action from the King of Bhutan, the country risks losing territory—China could claim the northern half, while India could establish dominance in the south.

Reaffirming his belief that Bhutan cannot survive without the institution of monarchy, Paudel urged the King of Bhutan to adopt a policy of national reconciliation and allow exiled citizens to return. He also called for the withdrawal of Indian military forces stationed in Bhutan.

He says if the Bhutanese refugees are not allowed to return, Bhutan will not survive. A country cannot exist without its people. A crown on a throne is not enough to build a nation.

A detailed conversation with Bhutanese leader Paudel—covering the present realities inside Bhutan, the situation of 7,000 to 8,000 refugees still living in Nepal, the fake refugee scandal, and other pressing issues—is presented here through the joint efforts of journalists Arun Baral, Sanket Koirala, and Ishwar Dev Khanal.

As the President of the Bhutan People’s Party, what is the current status of political parties in Bhutan? How many exist inside and outside the country? And what activities is your party currently involved in?

The first political party in Bhutan was the Bhutan State Congress Party, formed around 1948. The history of that party is long and complex—I’ve written about it in my book. Its founder, Mahasur Chhetri, was a low-level employee working in the Sarbhang office. He was later murdered and his body was thrown into a river.

The Bhutan People’s Party, which I chair, is the second political party in Bhutanese history. After that, other parties like the Druk National Congress were formed in exile. Later, when exiles settled in refugee camps, the Bhutan National Democratic Party (BNDP) was also formed.

Unfortunately, the leadership of all three major parties has passed away. R.K. Budhathoki was assassinated in 2001. BNDP president R.B. Basnet died due to illness. Ronthong Kinley also passed away under uncertain circumstances. He had come to Kathmandu to attend a meeting with us and also to teach a young Lama in Rungtek. He died there.

These parties still exist in name, but not much has been done in recent years. The Bhutan People’s Party has an active central committee. I serve as its President. Most of our members live outside Bhutan. We continue to organize programs according to our strategic plans and maintain contact with our members abroad.

However, we are currently unable to operate inside Bhutan. We’re not permitted to enter the country. One reason is the strict legal constraints within Bhutan. The other is that India has blocked our entry from the Kakarbhitta border, even though we carry refugee identity cards issued by UNHCR. As a result, we remain confined to Nepal.

At your age (73), do you still hold hope that you will return to Bhutan by raising a movement and making it successful?

The movement is far from over. Under our leadership, the third movement was repeatedly carried out inside Bhutan. Now, this is the beginning of the fourth movement.

The world only sees a few Bhutanese refugees in Nepal, assumes most have been resettled in third countries, and believes they are living comfortably. Meanwhile, Bhutan sends the message that Gross National Happiness (GNS) reigns and its people live happily. But why were we labeled Lhotshampa? What does Lhotshampa really mean? And what was Bhutan’s purpose in calling us that?

Lhotshampa literally means “southern people.” But if Ngalung people come from the north and settle, they are Ngalung, not Lhotshampa. It’s like saying a thief from the east is a thief, but if he steals at night wearing a tika (mark) claiming to protect the house, that’s deception. Bhutan branded only the Nepali community as Lhotshampa to stigmatize us.

It’s tragic that after expelling 150,000 Bhutanese, Bhutan declared itself a democracy. Rare is the history where a former king declares democracy while still wielding power behind the scenes—Jigme Singye Wangchuck rules quietly, holding his son’s (Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck) hand while sitting apart.

Democracy arrived, and the people should be happy. We never protested inside Bhutan or demanded that people leave. But since democracy was declared in 2008 and a new king ascended, Bhutanese have gradually migrated—mostly to Australia, the U.S., and Canada.

Over 60,000 Bhutanese citizens have resettled there, refusing to return. The country is becoming empty. If this trend continues, within a year or two, over 100,000 people will be living abroad.

Even those with Bhutanese citizenship have gone abroad; their families are not returning. Last year, the king urged them to come back and help develop the country, but history shows no such return. If this continues, how can the country survive?

Meanwhile, King Jigme proclaimed Gross National Happiness, while the Nepali community—the very people who developed Bhutan—were chased out with insults and discrimination. Now the country lies empty.

Once, cardamom, oranges, and rice were cultivated and grain was exported from Bhutan. Today, all these must be imported from India. The land is left uncultivated. There are no workers. Yet, they celebrate Gross National Happiness.

When we lived in Bhutan, its area was 46,500 square kilometers. Now, official maps show only 38,000 square kilometers. So where did approximately 8,100 square kilometers of land go?

Has it drifted north toward China, or south toward India?

Bhutan remains silent. Meanwhile, India loudly claims that China has encroached on the Doklam region. I’ve written about this in my book—Doklam lies in Bhutan’s Haa district, close to the Chinese border.

Historically, the Geological Survey of India conducted surveys in that area. Later, Bhutan’s own geological body declared that the region holds significant uranium deposits. A Bengali official once stated that uranium had been present there in large quantities for years—enough to meet Bhutan’s needs.

But according to a former Geological Survey employee, the man who made that claim mysteriously disappeared before his statement was publicly scrutinized.

China fears that India might extract uranium through Bhutan, perhaps even through underground tunnels. India, on the other hand, fears that China could do the same. This rivalry is fueling the ongoing tensions between the two powers.

Another contentious issue is the presence of military forces in Bhutan. The country has about 6,000–7,000 soldiers and roughly 10,000 police and security personnel. Yet, there are approximately 25,000 Indian troops stationed there, under various labels—engineers, road builders (IMTRAT, GREF and DANTAK), and others.

China sees Bhutan as a vessel for India’s influence—a small country housing a large Indian presence. Bhutan seems caught in the middle, trampled from the north by China and dominated from the south by India. But Bhutan remains silent. China stays quiet. Only India speaks out loudly.

There have been 25 rounds of talks to resolve Bhutan’s border issues. The 1949 and 2007 treaties obligate India to stay involved. Bhutan, for its part, made some progress and participated in the 24th and 25th rounds of dialogue. Still, the border dispute remains unresolved.

Based on my experience, and that of many Bhutanese intellectuals, I believe India should withdraw its economic and military presence from Bhutan. Bhutan is capable of defending and managing itself. If peace is truly the goal, then the King must take that bold step.

If it comes to war to defend our sovereignty, we are prepared. But peaceful negotiation is the better path. Bhutan must survive. And for Bhutan to survive, its monarchy must remain. If the monarchy falls, the nation will be torn in two—half taken by China, the rest absorbed into the south.

One distressing thing is what’s being said on Indian YouTube channels. There’s open speculation that Bhutan could become India’s 29th state. Tragically, Bhutan has not objected. Bhutan should raise its voice. After all, India making such a declaration is no trivial matter.

Speaking of perceptions—there are some opinions circulating in Nepal. Many say Bhutan has made impressive progress in South Asia. That it has boosted GNS and increased its GDP. Some say it’s transitioning from a third-world country to a first-world model. Relations with China are growing, and Bhutan now speaks to India on more equal footing. Do you think Bhutan is emerging from its so-called “Bhutanization”?

If things were really so good, why are so many Bhutanese leaving? Why did they flee to Australia? The government itself is facilitating their departure. Those who want to go must deposit one lakh rupees in a bank, which the government holds for documentation.

Then, the government helps them get visas. If a country like Australia approves it, they are allowed to go. A year later, that deposit is retained. Even now, Bhutan continues to send its people abroad.

If people were truly happy in Bhutan, would they be leaving? People don’t abandon their country unless they’re economically strained or feel unsafe. If both conditions were fine, why would they migrate?

Do you still love Bhutan as deeply as before?

Of course. One’s homeland is a gift. The first sip of water you drink—that’s like your mother’s milk. Bhutan is naturally beautiful. Its rivers and streams rarely flood. Landslides are uncommon compared to many other countries. Only recently, with deforestation, has some damage occurred—something that never used to happen.

You previously said India should withdraw its army from Bhutan and that the King should take initiative. What message would you like to send to the King of Bhutan?

I’ve written it clearly in my book: the King must lead a process of reconciliation. The Bhutanese in exile possess great potential—some are doctors, scientists, successful businesspeople. Their talents should be brought back to Bhutan for the nation’s development. There’s no alternative.

To the King—and to the international community—I say this: If these refugees are not allowed to return, Bhutan will not survive. A country cannot exist without its people. A crown on a throne is not enough to build a nation. Development requires labor and commitment. Can Bhutan import youth workers while its own remain in exile?

Perhaps the King fears that bringing back refugees could destabilize his rule. But I believe this: if there is no monarchy, there will be no Bhutan.

Are you a monarchist, then?

Absolutely. Perhaps even more so than the King himself. Anyone can wear a crown, but without a monarchy, Bhutan cannot hold together. Why else would a nation of just 600,000 people be so deeply divided? Bhutan should decentralize and develop, not expel its people. Expulsion weakens a nation; it doesn’t build one.

But for any political movement to succeed, doesn’t it also need support from within Bhutan—not just from exiles abroad?

Certainly. But sometimes movements begin from outside. What’s happening now—especially the way Bhutanese youth are organizing abroad—is encouraging.

For example, there’s a major week-long event happening in Ohio, USA. Bhutanese refugees from around the world will gather. Over 50,000 people are expected. It’s not just a celebration—it’s a symbolic bugle call, a message of unity, identity, and faith.

Back in Bhutan, the Nepali-speaking community in the south is alert and hardworking. But some regions remain deeply underdeveloped. Take the Drukpa community, for instance. They still wear clothes made from goat skins, live nomadically in cowsheds, moving from pasture to pasture.

They carry their entire lives with them—grinding stones, turbans, everything. There’s no formal education. They haven’t had the opportunity to study.

People say education is free in Bhutan. That’s true—we studied for free too. But is it really accessible? Can a student from one remote hill walk to another just to attend school if there’s no road? Can a sick person from a distant village reach a health post if there’s no infrastructure?

Now you live in Nepal, which has its own governance issues. People talk about “Sikkimization”, “Bhutanization”, even “Tibetization”. As someone seeking a connection to the land, how do you view Nepal’s situation?

First, Nepalis must touch their soil—feel their land—before forming political opinions.

During the monarchy, we constantly heard on Radio Nepal how Nepal was progressing, how there was no other country like it. I remember hearing King Mahendra speak in Biratnagar—his voice still echoes in my memory. Even now, when former King Gyanendra speaks, that familiarity returns.

Yes, the people demanded a republic. And the royal family they once trusted was tragically lost. Another royal was crowned, and then came the republic. That, in itself, isn’t wrong. But what’s tragic is that Nepal did not transition toward an economic revolution.

After abolishing the monarchy, Nepal should have established a permanent government. That didn’t happen either. Today’s politics feels even more chaotic than before. Nepal must not suffer more. It must not become a victim of its own politics. It must not fall apart.

Yes, perhaps no one listens to the voices of refugees. But still—every citizen must love their land. People say Nepal has nothing. That’s not true. It has plenty. But we still can’t answer the most important question: why has it not developed?

You currently live in Jhapa. What is the current population in the refugee camps in Jhapa and Morang?

There are approximately 6,500 registered refugees still living in the camps. In addition, around 1,000 are unregistered. Right now, there are roughly four categories of refugees: Registered refugees — Those who completed all procedures for third-country resettlement but were stopped at the airport—they’ve become victims all over again

Unregistered refugees: Recent arrivals — refugees who had gone to the U.S., then returned to Bhutan via India, and came back to Nepal. About 25 or 26 people have reportedly been deported in this way, although exact data is unclear.

Why were some Bhutanese deported from the United States?

Mostly due to misunderstandings of the local laws. For example, in a domestic dispute, if a wife calls the police and claims domestic violence, it can have serious legal consequences—even if the situation is not criminal. Such misunderstandings led to some deportations.

Under Trump’s new immigration policies, how safe are Bhutanese refugees currently living in the U.S.? You likely have relatives there—what are you hearing from them?

According to UNHCR, around 119,000 Bhutanese refugees have been resettled in countries including the U.S. Those who became legal citizens and live honestly are not facing significant problems.

But based on what I hear, many of them still live in fear. The current atmosphere—where there’s suspicion between fake and genuine refugees—has created uncertainty. We are genuine refugees, and it is frustrating to see this confusion.

Recently, Nepali citizens attempted to travel to the U.S. by posing as fake Bhutanese refugees, sparking a major scandal. Even Tek Nath Rizal’s name came up. As a real refugee, how did this news affect you?

What can I say? It highlights how many privileges some Nepali citizens enjoy in the post-republic era—perhaps even more than genuine refugees.

Ironically, when today’s genuine refugees meet high-level officials—from the Prime Minister to the Chief District Officer—and explain their hardship, we’re told: “Let that fake refugee case conclude first, then your case will move forward and you’ll get justice.”

Having said that, the fake refugee case has definitely had a negative impact on Bhutanese refugees who have prepared their documents to resettle in a third country, hasn’t it?

Anyone with common sense would agree that it has. But let me share a story. A small, three-month-old deer calf went to drink water from a river. Not far away, a wolf came to drink as well. The wolf found a pretext to accuse the calf, saying, “Why did you muddy the water I was drinking? You did the same thing last year.”

The calf replied, “I was only born three months ago. What did I do last year?” Shortly after, the wolf devoured the calf.

Our situation as refugees is much like that deer calf. We don’t know who created the fake refugee cases, who fabricated them, why they were made, or how they were sold.

But is it right to dismiss the suffering of genuine refugees—who have lived in exile for 30 years—by labeling their plight as “fake”? The government that leads this republic and the Nepali people should understand this.

Have you raised this question with the Nepal government?

The Ministry of Home Affairs is the last place we turn to. Last year, we came to Kathmandu and presented our concerns.

Did you meet Balkrishna Khand or Rabi Lamichhane?

At that time, Narayan Kaji Shrestha was the Home Minister. We met him and lodged our complaint.

What was his response?

He said the cabinet had met recently and decisions would be made soon. He asked us to come back with confidence, assuring us things would be resolved. We brought many demands. When he said there were problems with some issues and asked us to submit them in writing, we did. But then he was replaced, and the government changed. He never returned to address the matter.

Party secretaries later met Home Minister Rabi Lamichhane. He asked us to wait patiently. However, he too did not stay long. He has since disappeared but will have to be held accountable eventually.

I say this book should be submitted to the government—just in case they have not yet understood the gravity of the situation.

Comment