SUNSARI: In the settlements along the banks of the Koshi River, one common phrase captures the passing of time: “How much water has flowed in the Koshi?”

The struggles of the people who depend on this river for their livelihoods echo the changing waves of the Koshi. Over the past century, the river itself has shifted—sometimes flowing east, other times west—forcing settlements to relocate and lives to adapt along with it.

The story of the Koshi’s cattle herders, who once roamed its banks playing ‘pauthe jori’ (a game played by locals), mirrors this restless rhythm.

In 1985 B.S., the Koshi flowed near what is now its eastern embankment. But the river has never stayed still for long. Elderly locals recall stories passed down from their grandparents about life by the Koshi—filled with both beauty and hardship.

Former MP Ananda Prasad Gautam (84), a resident of Sundar Gundar Chatara Village Panchayat in Beli Mauje—now Barahakshetra Municipality-2—has witnessed many such changes.

“The Saptakoshi River has changed its course many times over the past century,” he recalls. “After each monsoon, the river found a new path.” Gautam remembers major floods in the Nepali years of 1990, 2011, 2022, 2024, 2025, 2038, 2040, 2042, 2045, 2065, 2079, and 2081 BS.

Once, every household in Tappu raised buffaloes, supported by abundant grazing land. Although some still maintain half an acre for cattle, commercial farming has not taken off widely, says Raut.

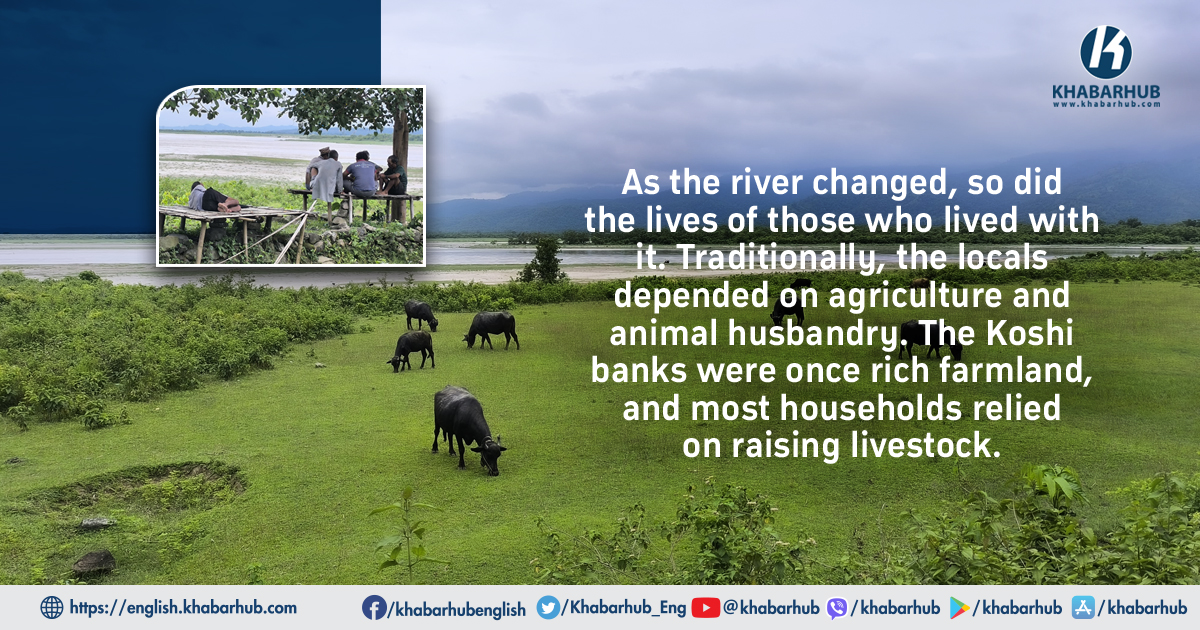

As the river changed, so did the lives of those who lived with it. Traditionally, the locals depended on agriculture and animal husbandry. The Koshi banks were once rich farmland, and most households relied on raising livestock.

Shepherds would drive large herds across the river to graze on Tikris—small river islands. In 2025 B.S., Gautam had over 200 cattle in his cowshed. “We didn’t count every single one,” he says, “but we used to look after at least 100 to 150 cattle across the river. The calves stayed in the cowshed.”

Cowsheds lined the riverbank, each holding hundreds of cattle. Milk production and cattle rearing were the primary livelihoods. Every morning, the herds were taken across the river to graze, returning on their own by evening.

“We used to swim across the Koshi holding onto the cows’ tails as kids,” Gautam recalls with a laugh. “Looking back, it was dangerous, but also full of joy.”

But in the last decade, the number of cattle herded in the Koshi has dwindled sharply. Gautam’s cowshed has been reduced to a single cow and calf. Younger generations have shown little interest in traditional cattle farming.

With family members opting for jobs or foreign employment, and fewer workers available to manage the herds, the practice has faded. Disease has also claimed many animals, leaving cowsheds empty.

Shivnarayan Chaudhary (64), a cattle herder from Barahakshetra-4, Dhanpuri, has continued his ancestral occupation. He currently manages 10–12 cattle along the Koshi’s banks. But he stops grazing them during the monsoon and says the energy and enthusiasm among herders is fading.

He notes that herders from Thakurbari in Barahakshetra-6 have stopped taking their cattle to graze on Tikris in Tappu. “After the rains, I resumed cattle grazing, but the practice of crossing the river with cattle is dying out,” he says. “Times have changed. Herding cattle has become a sad profession.”

Chaudhary recalls Singh Bahadur Tamang of Bharauli, once the area’s largest cattle owner, who kept over 200 cattle. “Now, Singh Bahadur is gone, and so are his cattle. The cowshed stands empty.”

Herding cattle was once a daily routine for residents of settlements along the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, stretching from Chatara to Rajabas Prakashpur.

Locals from Garaiya and Chiliya Tappu on the opposite bank also grazed their animals on the Tikris. However, over time, this longstanding custom has gradually disappeared.

“Nature has protected us, those born on the banks of the Koshi. We have survived countless floods and disasters, constantly adapting and advancing the civilization along the Koshi,” says Pradeep Karki, a young sociologist from Barahakshetra-2. “We are the living characters in the story of the Koshi.”

Youth moving toward modern animal husbandry

Bijay Kumar Raut (35) spent much of his youth as a shepherd in Chiliya, Tappu, Sri Lanka, tending to herds of 20 to 22 buffalo. His journey into professional cattle rearing spanned from 2063 to 2066 BS, but he was forced to stop due to disease outbreaks.

The Koshi region holds significant potential for commercial animal husbandry. Bharat Yadav, a young entrepreneur and practitioner of his ancestral farming profession, exemplifies this new generation of farmers.

“I saw the potential in commercial cattle farming but suffered heavy losses because of disease,” he explains. Now active in politics, Raut has left Tappu behind.

Once, every household in Tappu raised buffaloes, supported by abundant grazing land. Although some still maintain half an acre for cattle, commercial farming has not taken off widely, says Raut.

Meanwhile, cattle farming in the Koshi Tikris is slowly modernizing. While the old herders’ sheds are deteriorating, many young people still see agriculture and animal husbandry as foundations for prosperity.

One such example is Kailash Karki (41), who has been raising cattle for the past seven months in Jalal Tikri, Barahakshetra-6. He currently has 150 cattle and, together with his group, cultivates maize on 120 bighas of land alongside commercial cattle farming.

They have even installed silage machines to produce hay from their maize crops. “We’ve begun commercial farming with the goal of prosperity through agriculture,” says Karki. “Our vision is to develop agriculture and animal husbandry not as traditional practices but as productive and industrialized sectors.”

The Koshi region holds significant potential for commercial animal husbandry. Bharat Yadav, a young entrepreneur and practitioner of his ancestral farming profession, exemplifies this new generation of farmers.

After crossing the Sisauli Ghat in Barahakshetra-6, visitors can reach Yadav’s cowshed, which is also accessible from Belka Rampur in Udayapur. His farm houses 100 buffaloes and 40 cows out of a total herd of 300, with the remainder grazing in the nearby forest.

Comment