KATHMANDU: Despite spending over Rs 110 million in capital expenditure across six years, Nepal’s grand vision of establishing a riverine shipping system on the Koshi River remains mostly a paper exercise.

What was once touted as a leap toward water-based transport and tourism has ended up as another example of how public money can be spent with little accountability, negligible results, and confusion among stakeholders.

With just two months left until mid-monsoon — the peak time for river traffic — the reality on the ground is grim.

The Koshi River, once imagined as a route for vibrant waterway transport, still lacks a well-organized and navigable system. Passengers face daily obstacles due to unremoved river stones and blocked paths, while private operators are left struggling to function.

The shipping dreams began with the establishment of the Koshi River-based Water Tourism and Shipping Office, which came with a budget of over Rs 152 million spread over six fiscal years.

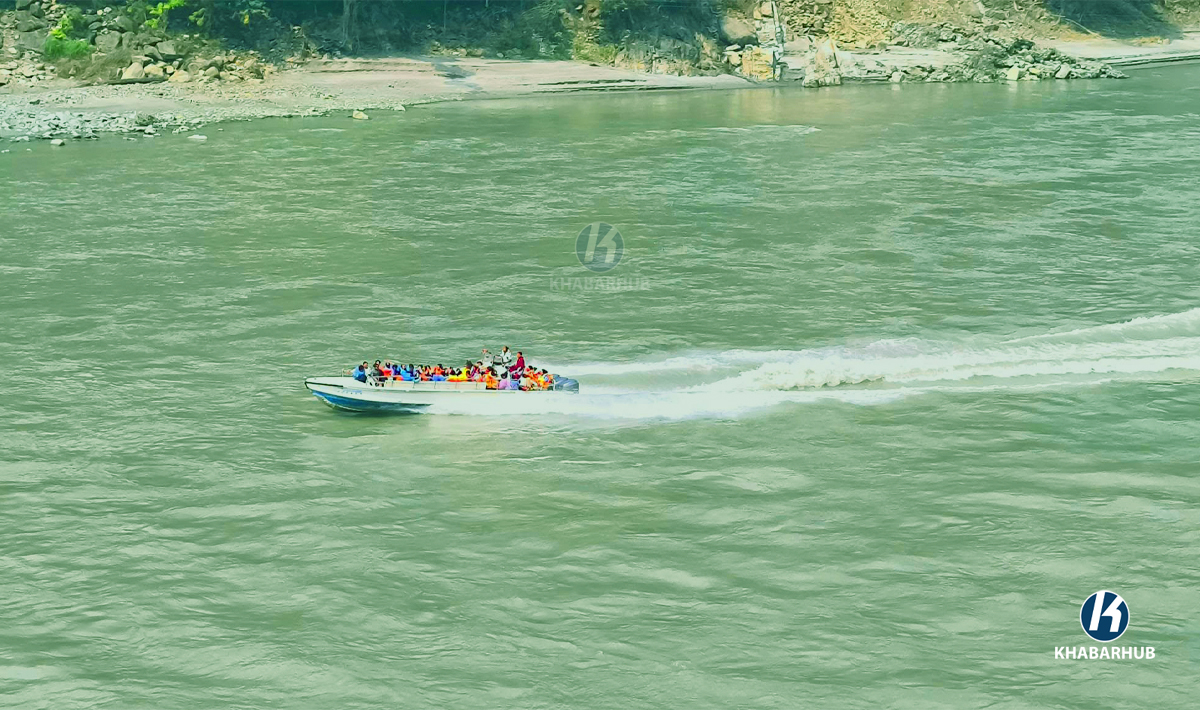

Of that, more than Rs 110 million was funneled into capital expenditure. Yet, there is little visible on the ground: no terminals, no reliable routes, and no infrastructure to show for the money spent. The only vessels in operation are a handful of jet boats.

No legal foundation

In Parliament, Rastriya Swatantra Party MP Sobita Gautam raised a crucial question: Why was the Shipping Office established without first enacting a proper legal framework? The response from the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport was revealing: while millions were spent and feasibility studies were carried out on various rivers, the transparency and public disclosure of these works were minimal at best.

Minister Devendra Dahal listed several studies and plans — from Arun Dobhan to Ranitar, Chatara to Tumlingtar, even up the tributaries of Tamakoshi, Dudhkoshi, and Sunkoshi. Yet local stakeholders, including jet boat entrepreneurs and municipal officials, say they are unaware of any such activities.

“Nothing official has come out except for rumors,” said jet boat operato.

DPRs that go nowhere

The government claims to have conducted detailed project reports (DPRs) for the construction of terminals and for removing river obstacles. However, local authorities like Barahachhetra Mayor Ramesh Karki say they have seen no such plans in action.

He admits that although he visited the Shipping Office to bring water transport under tax regulation, no legal clarity or cooperation followed.

“They told us not to bother them without a law,” he said.

In theory, the Office even allocated Rs. 1 million to clear river blockages using an excavator. Work started on January 15, but within just seven days, it stopped without progress. No significant results were achieved, leaving river stones untouched and blocking boat routes.

“We were happy the work had begun, even if late,” said one hopeful entrepreneur. “But nothing came of it.”

Passengers forced to walk

The lack of river maintenance means passengers often have to disembark, walk along the banks for 10 to 15 minutes, and then board another boat — a tiring, unsafe, and inefficient process.

Boat operator Sujan Shrestha notes that until the river stones are removed, this process will continue. He believes a clean river route could allow jet boats to operate all the way to Dolalghat — if only the government would act.

A local commuter, Milan Kumar Rai, expressed his frustration: “Earlier, we used to travel even without cars. Now, we are forced to use boats and walk halfway due to river blockages.”

Investment sinking

Of the eight boat companies registered on the Koshi River, only one — the KIAN-1 of Barahakshetra Water Transport and Tourism Services — remains operational. The rest are sidelined, their vessels parked idly due to blocked paths and damaged docking areas.

Many of these companies have made significant private investments. For example, DB Karki of Koshi Adventure Pvt. Ltd. spent Rs. 18 million on two OBM boats, which now sit idle due to navigational hazards.

“If one of these boats hits a stone, it’ll cost Rs 1.5 million in damage,” said Karki. “Without state-led clearing of the waterway, our investments are just rusting away.”

Washed-up policies

Adding to the woes is the absence of docking infrastructure. Floods last year washed away the only proper port at Chataraghat. Boat operators have since been left without a safe place to park or load passengers.

“Koshi floods took more than just money — they took our ability to function,” said entrepreneur Ramesh Karki. He claims over Rs. 500,000 worth of infrastructure was destroyed, and no state assistance or policy has followed to rebuild or regulate water transport.

Even though the Barahachhetra Municipality’s city development plan mentions bringing boat services under a tax regime, no implementation has occurred. Operators are willing to pay taxes if services and facilities were provided in return, but without state investment, it becomes a one-sided burden.

A System Without Direction

Nepal’s shipping experiment has become a classic case of bureaucratic overreach without grassroots grounding. Feasibility studies, budget allocations, and DPRs may look good on paper, but they fail in execution when local officials and entrepreneurs are left in the dark.

Despite millions spent, river travel is still a risky and fragmented endeavor. The Trishule boat stops short of its route due to blocked stones. Entrepreneurs have their boats grounded. Municipal offices have no idea what’s being planned, and passengers are left walking along muddy riverbanks.

Comment