KATHMANDU: Lit Tazewell, an American teacher, vividly recalls his transformative experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal four decades ago.

The year was 1984, and Lit, still in his youth and unmarried, found himself immersed in the remote villages of Nepal, where communication was a challenge without the modern conveniences of telephones, mobile phones, or email.

Assigned to Mauna Budhuk School in Chaubise Rural Municipality-7 of Dhankuta district, Lit navigated the challenging terrain, reaching to Bhedetar from Dharan by car and then trekking for 5-6 hours through Kuibhir to reach the school.

This experience not only tested his resilience but also provided an invaluable opportunity to delve into the heart of Nepali society and culture.

Reflecting on his time in Nepal, Lit emphasized the profound changes he witnessed during his recent visit to Kathmandu.

Having also worked in Africa and Central Asia as part of the U.S. aid organization USAID after his Peace Corps stint, Lit returned to Nepal for an Asia-level program organized by USAID.

During his five-day stay in Kathmandu, Khabarhub seized the chance to interview Lit and gain insights into his impressions of Nepal then and now.

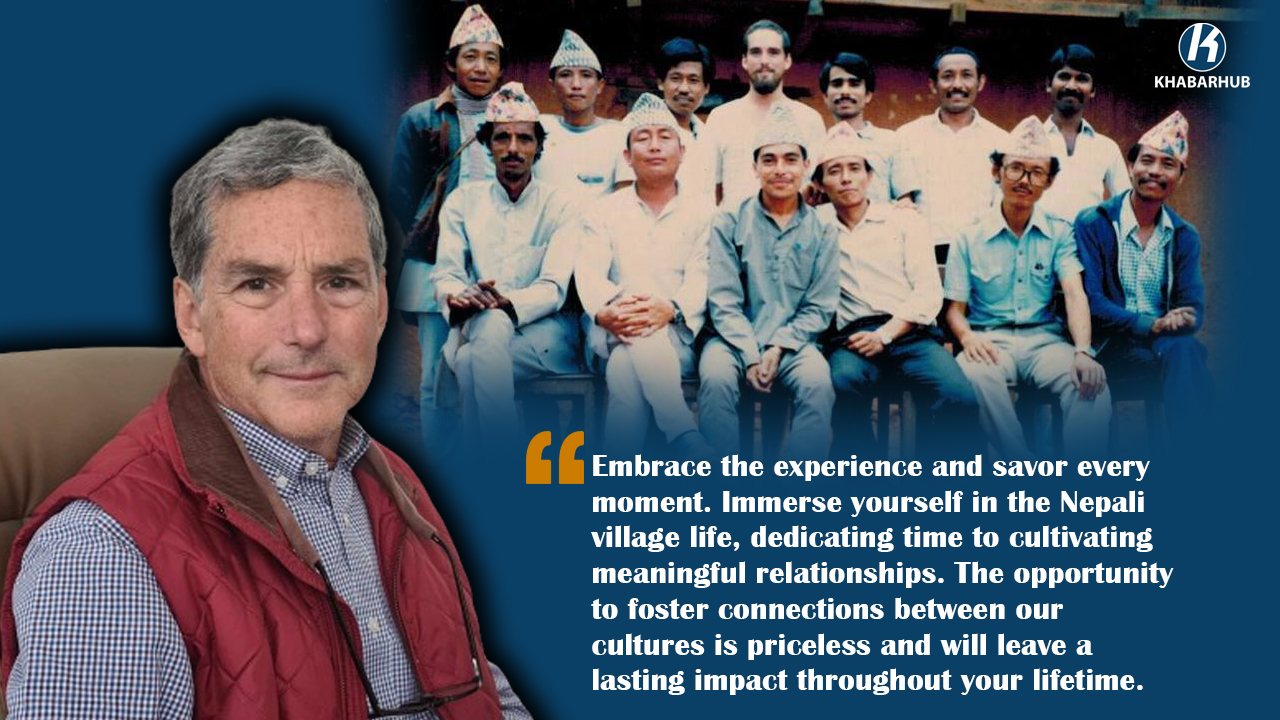

In a conversation with Khabarhub, Lit Tazewell, a US citizen, shared his experiences as a Peace Corps volunteer from 1984 to 1987, offering a captivating glimpse into the bygone era and the lasting impact of his service on his understanding of Nepal and its people. Excerpts:

Can you tell us about your journey to Nepal as a Peace Corps volunteer?

In 1984, I embarked on a transformative journey to Nepal as a Peace Corps volunteer, fueled by the anticipation of exploring the then kingdom, its rich culture, and the majestic Himalayas.

Following a comprehensive three-month training with the Peace Corps, I found myself at Mauna Buduk Secondary School, where I delved into the Nepali language and honed my teaching methodologies for imparting English education.

Why did you choose to join the Peace Corps and volunteer here in Nepal?

Raised with a sense of duty instilled by my military officer father and inspired by early exposure to diverse cultures during European travels, I felt a calling to contribute meaningfully.

A stint in Haiti, witnessing stark poverty, fueled my desire to address global challenges.

Applying to the Peace Corps after my return, I expressed a preference for Nepal, aligning with my aspiration to work in the service sector.

This journey, particularly in Nepal, became a fulfilling chapter driven by a genuine commitment to positive impact.

What was your first experience in the school?

As the first person from the USA or Europe to set foot in Mouna Buduk School, I became the center of attention, with locals gathering around out of curiosity.

This transformative period marked a stark departure from my home life, initiating a unique cultural exchange.

What activities were you involved in?

During my two years at Mauna Buduk Secondary School, my involvement extended far beyond the confines of the classroom.

I took up residence at the village health post, forging connections with health workers, villagers, teachers, and community leaders.

In addition to my teaching responsibilities, Harka Prasad Lama and leader Rajendra Chemjong encouraged my participation in diverse activities, such as providing training on preserving oranges for export and enhancing the teaching capabilities of primary school educators.

I also had the privilege of visiting other schools, observing teaching methodologies, and exploring the surrounding areas.

Against the backdrop of the challenges of the 1980s, open defecation emerged as a critical issue with numerous associated health concerns.

In response, I initiated a novel approach—a latrine building competition among class 10 students.

The winning student was awarded a cash prize, sparking the construction of numerous latrines.

As part of this initiative, I joined health workers and community educators in visiting each house that built a latrine.

Our activities included documenting family details, conducting surveys on sanitary practices, and observing construction techniques to determine the competition winner.

Additionally, in collaboration with the Save the Children Maternal Child Health Clinic, we constructed smokeless stoves using mud and stones.

These stoves served a dual purpose by fostering health interactions among teachers and the community, addressing sanitary concerns, and promoting the use of cleaner energy sources.

Adding an innovative touch, we organized the first-ever village screening of the documentary “Fragile Mountains,” which addressed deforestation, the use of smokeless stoves, and biogas, facilitated by a projector and generator.

Following my teacher training, a similar program was launched for traditional healers, locally known as “Dhami” and “Jhakri”, with the support of the health post and the Save the Children Maternal Child Health Program.

In collaboration with Ashok Sharma, a community health educator, we developed a curriculum based on mutual respect for the roles of traditional and Western healing methods.

The program aimed to blend these approaches, especially in treating illnesses like diarrhea and pneumonia.

The training involved a three-day session where DhamiJankri and health workers demonstrated their techniques.

Subsequently, I returned to the USA, leaving behind a foundation for continued collaboration and community health improvement.

What did you do after you returned to the United States?

Upon my return to the USA, I embarked on two significant paths.

Firstly, I enrolled in law school, immersing myself in a new realm of learning.

Subsequently, my professional journey took an unexpected turn when, a year later, I discovered the presence of USAID in Kathmandu.

This revelation prompted me to connect with a lawyer associated with USAID, rekindling my ties with Nepal and Mauna Buduk.

During my revisit, as I traversed the trails, I encountered one of the DhamiJankri.

The reunion, after two years, took an unexpected twist as the Jankri requested referral slips, emphasizing the need for refreshers given the elapsed time since our initial training. This revelation left me astonished.

Returning to the village, I discovered a transformative change—nearly every home now boasted a latrine and smokeless stove.

The teachers, through their diligent follow-up, had undertaken incredible work, leaving a lasting impact on the community. The visible progress underscored the enduring positive changes spurred by our earlier initiatives.

How do you feel about Mauna Buduk?

Reflecting on my time in Mauna Buduk, the warmth and acceptance of the villagers remain indelibly etched in my memories.

Their hospitality went beyond mere tolerance – I was consistently invited into people’s homes for “Dal Bhaat”, and I became an integral part of their major celebrations such as Dashain, Tihar, and other cultural festivities.

This sense of inclusion in their cultural traditions forged a profound connection, making my time in Mauna Buduk exceptionally enriching.

What did you take away from that time?

My experience in Mauna Buduk has left an indelible mark on me. Despite being an economically modest community, the residents, predominantly farmers surviving on rice, millet, and oranges, were exceptionally rich in culture and love.

The profound sense of community surpassed my expectations, resonating strongly with my own experiences.

The similarities in our day-to-day lives and relationships were remarkably robust, leaving a lasting impact.

These fundamental aspects of life that I encountered in Mauna Buduk have remained with me, shaping my worldview.

Moreover, my time in Nepal proved pivotal, offering insights into Hinduism, the teachings of the Gita, the traditions of the Limbu community, and Buddhism.

I seized the opportunity to delve deeper into spirituality by undertaking a Bipasana meditation course in Kathmandu.

The chance to visit Khaptad Baba before his passing marked a significant spiritual awakening.

Furthermore, I found myself transformed into a more mature and grounded individual.

The values I embraced during my time in Mauna Buduk became the guiding principles for my career.

Despite initially starting as a corporate lawyer, I transitioned into the development field with USAID.

Over the years, I worked on assignments across the globe, culminating in my retirement three years ago.

My final role as the Mission Director in Malawi, Africa, was a testament to the lasting impact of my experiences in Nepal, which have always held a special place in my heart.

Reflecting on your global experiences, what fascinates you most about Nepal compared to other nations?

Indeed, making direct comparisons is complex, as each country boasts its unique challenges, richness, and beauty.

However, what set Nepal apart for me was the unparalleled opportunity to fully immerse myself within a community, establish deep friendships, and cultivate enduring relationships.

A recent poignant example of this enduring connection was attending a wedding with one of my language teachers from the Peace Corps.

This experience highlighted how my time in Nepal continues to exert a profound influence on my life.

In drawing parallels, I would emphasize the striking similarities between Nepal and Malawi, characterized by exceptional hospitality.

Both countries share common features, being landlocked, economically modest, and with limited exports, yet they exude a warm and inviting spirit.

While Malawi’s beauty is undeniable, Nepal holds a unique position at the zenith of my experiences, distinguished by its exceptional charm and enduring significance in shaping the course of my life.

How do you currently perceive Nepal?

During my recent return, my exploration has been confined to specific areas of Kathmandu.

The Kathmandu Valley has evidently undergone substantial development, characterized by increased congestion and heightened pollution levels.

While air quality has been a historical concern, it appears to have worsened, prompting apprehensions and underscoring the urgency for Nepal to explore cleaner energy alternatives through harnessing its water resources.

Despite these environmental concerns, it’s crucial to acknowledge the commendable advancements in infrastructure, including improved access to electricity, telecommunications, and reliable internet services.

The effective use of technology is noteworthy. What particularly stands out is the prevailing sense of security in Nepal.

Unlike some other nations, the specter of street robberies never loomed, showcasing an exceptional level of safety rooted deeply in the country’s culture –a strength often underestimated but clearly thriving among local communities.

In my perception, Nepal remains a profoundly spiritual country.

Looking ahead, I am eager to return next year, conduct a more extensive exploration, and provide a more comprehensive commentary on the evolving landscape.

Lastly, what advice do you want to give to those who are still volunteering in Nepal as a Peace Corps volunteer?

My advice is simple: savor the experience. Seize the opportunity to immerse yourself in a village, and invest time in building relationships.

The chance to forge connections between our cultures is invaluable and will endure for a lifetime.

These interactions have the power to significantly impact not only the community you are serving but also your own life in profound ways.

Embrace the journey, relish the cultural exchange, and cherish the lasting bonds you create during your time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal.

Comment