KATHMANDU: The Nepal Army (NA), which has been striving for organizational restructuring, has adopted a new structure — the Command Headquarters model — in a war-centric approach.

At a time when the country is reeling under political imbroglio, the NA has embraced a new structure by scrapping the erstwhile divisions.

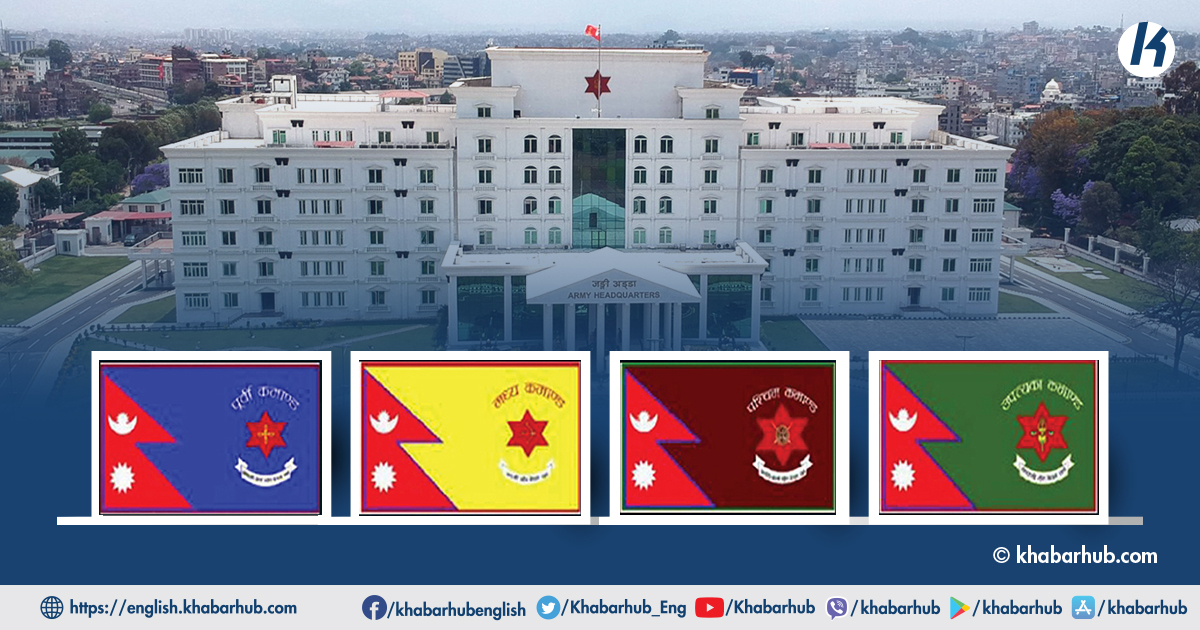

Doing away with the old divisions in the NA, four Command Headquarters have been created and enforced, adopting a “Three Plus One” concept in the army structure.

With the new structure in place, the East Command Headquarters, Mid-Command Headquarters, West Command Headquarters, and Kathmandu Valley Command Headquarters — each led by a Commander (two-star Major General) — have come into operation.

After the restructuring, the centralized operational responsibility of the NA is devolved and rests on the four Command Headquarters, which will mobilize the battalions and other units under them.

The rationale behind the restructuring is to make the Command Headquarters assume tactical responsibility of the operational battalions and other units under them, leveraging the National Headquarters to focus on strategies of national significance.

Each Command Headquarters will have its own Air Base, Logistics Base, Intelligence Base, Recruitment Center, and a Reserve Battalion.

However, with the embrace of the new administrative structure, the command and control of lower echelons of the NA also need to be altered.

The existing 18 brigades (led by Brigadier Generals) across the country now come under the jurisdiction of the four Commands. After the transition, the Commands will have a varying number of brigades under them; 7 brigades may be under one Command, 6 in the other, and 5 in the next one, depending on the geographic and strategic requirements.

Provided the command structure is developed into centralized command and the power is delegated as conceived in the structural plan, the new structure is likely to transform NA into a more professional organization in the future.

The NA, which had taken to Seven Plus One Division (one division each in the seven provinces and remaining one in Kathmandu Valley) model, has now taken to the “Three Plus One” Command Headquarters structure of late.

Three Commands are based on territories separated by the three major river basins of Nepal (Koshi, Gandaki and Karnali) and the one remaining Command is strategically based in Kathmandu Valley, keeping in mind the capital. The three commands, outside the capital Valley, will also shoulder responsibilities related to the North and South.

The NA, which had been advocating for a new strategy, has implemented the Command model before the start of the new fiscal year. And, so as to manage the ranks of many Major Generals at the military headquarters, the rank of Brigadier General has also been raised to the rank of Major General.

As the Maoist insurgency escalated, the size of the Nepali army doubled in five years. At the time the NA had been divided into six Divisions Headquarters — one Division in each development region and one in the Valley — in perfect harmony with the then five administrative divisions — development regions — of Nepal. But the Division Headquarters seemed ill-equipped with logistics and resources needed for their operation.

Though there had been a debate to make the organizational structure effective by forming a core structure, it never manifested. To harmonize with the transition to federalism in Nepal, the NA had added two more divisions — one each in Province 2 and Province 5.

Now that the army has been reorganized into the new Command Headquarters structure, it is likely that a Core Structure will be established to efficiently coordinate the organization.

The NA has always operated through a very centralized system. Though the debate on the Core structure for command and control and coordination in the army as an organization has been going on for two decades, it has not been implemented yet.

The Chief of Army Staff (COAS) has forever wielded absolute authority over the organization. Even in the Division Headquarters model, the Army Headquarters and the COAS used to be involved or awaited in most of the operations, even on the battlefield.

Although the new Command Headquarters model is a step forward to make the army agile, it is not yet clear how much the new structure, in the face of limited resources, can enhance the organizational capacity.

As the Army Headquarters has been criticized for engaging in day-to-day army affairs, even at lower levels, instead of being invested in strategic and policy affairs, implementation of the new Command Headquarters structure and the delegation of authority might be regarded as indicators of progressive success.

Without adequate resources and devolved authority, it is not possible to conduct operations smoothly, and there is no room for Commanders to exercise their discretion as there are several boundaries for officers in the army.

Now, the change in the command structure alone cannot bring substantive changes in the organization. As NA officers have been brought up in a core boundary concept, the Commander does not enjoy enough leeway to materialize his/her creative ideas.

Provided that the Command Headquarters structure is developed into centralized Core Command and the power is delegated to other Commands as conceived in the structural plan, the new structure is likely to transform the NA into a more professional organization in the future.

Structural transformation made possible through General Thapa’s initiation

The new structure of the NA is not based on a study or research of any political or civilian leadership.

The issue of Command structure had been under discussion in the army for long. The NA repeatedly prepared study reports, internally, and submitted them to the Ministry of Defense.

When the country formally adopted federalism by incorporating it in the 2015 Constitution, the NA restructured itself as per the changed context.

However, Chief of Army Staff General Purna Chandra Thapa was not satisfied with the practice of provincial structures. He believed in the deployment of the army based on geography and strategic importance rather than administrative and political restructuring.

After Thapa was assured of the responsibility of the CoAS, he wanted to make the command structure of the army war-centric, with a strong Israeli model of intelligence. He also studied how the capabilities of the army could change in a new administrative structure, and whether the current resources would suffice.

CoAS General Thapa was thinking of strategic deployment of the army on the basis of geography, bearing in mind the geopolitical and strategic environment, the operational capability of the army, and the integrated intelligence system.

As General Thapa’s term is coming to an end, he wants to see the priorities led forward during his tenure. The army’s new priorities are intelligence and military diplomacy.

From the moment he took office, COAS General Thapa expedited research and discussion on the issue and compiled a range of suggestions.

After a few years of preparation, the Nepal Army has adopted a new administrative structure. The army went for the implementation of the new restructuring plan after getting its proposal approved by the cabinet in February.

The new plan is being implemented prior to the retirement of the General who worked hard on it. General Purna Chandra Thapa, who has completed his tenure in office, will be on leave from July 8.

The organization, which had been running smoothly by practicing the old structure for long, likely feels a jerk at the enforcement of the new plan.

Eyeing at the probable uneasiness, the organization has started exercising the Command structure and has made necessary appointments accordingly, prior to the final date of mandatory transformation. The work of adjusting the hierarchy has also started internally.

The army, which almost doubled in size during the armed conflict, has been running a command structure guided by Division Headquarters for the past two decades. The army had embraced such a structure to make it easy for the organization to tackle the Maoist insurgency.

However, the relevance of the structure formed to tackle insurgency, in a way, has turned outdated after the settlement of the conflict.

The integrated command structure the army has adopted is based on the integrated security strategy the NA strives for, in accordance with the spirit of national security policy, the constitution, the defense policy, military strategy, and the military act.

The newly introduced structure has envisioned gaining power through decentralization, making the lower echelons responsible for logistics bases, training, routine exercises, technology-friendly barracks, integrated commands, integrated intelligence systems, and delegating authority to regional commanders based on research on external experience and the geography of Nepal.

Although the scarcity of resources can turn out to be a big challenge in implementing the plan, the attempt can be a step forward towards modernity, provided it is driven forward as per the spirit of the plan made to enhance the structural stability and the strength of the army.

NA trying to enhance strength through policy and structural stability

The integrated command structure the army has adopted is based on the integrated security strategy the NA strives for, in accordance with the spirit of national security policy, the constitution, the defense policy, military strategy, and the military act.

Obviously, now it wants to focus on its other priorities. As General Thapa’s term is coming to an end, he wants to see the priorities advancing after his tenure. The army’s new priorities are intelligence and military diplomacy.

With General Thapa’s arrival, the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) has become very powerful. In terms of capacity and information gathering, the DMI is far more capable than the National Investigation Department (NID), which has around 3,000 recruits working for it.

Nepal’s main intelligence agency is focused on political activity. As politics is likely to escalate into geopolitical tensions, the NA wants to set up an intelligence mechanism under its leadership.

For efficient operation, the number of army personnel deployed to secondary activities has to be reconsidered. Deployment of Army personnel in unnecessary locations has weakened professional capability to conduct operations, train, perform, and control.

Although the NID, Nepal Police, Armed Police Force, and others have been collecting intelligence, the NA wants to keep the intelligence agency under its control to prevent leakage of sensitive information gathered by these organizations.

As soon as KP Oli became the Prime Minister, as per the suggestion from his close quarters, he brought the concept of a National Security Adviser.

However, the plan did not materialize due to the army’s indifference to it. It is said that the army had reservations about the plan. Currently, the army chief is the chief security and intelligence advisor to the prime minister and the president.

Although CoAS Thapa wanted structural integration to be under the NA leadership, political tensions delayed the army’s plan. However, owing to a good understanding between CoAS Thapa and the head of the government, it is still likely to happen.

The NA has submitted a draft of the Military Intelligence Service Regulations to the Ministry of Defense. Similarly, the army has also proposed a National Integrated Intelligence Committee headed by the Chief of Army Staff, Chief of Armed Police Force, Nepal Police and National Investigation Department, and the Director-General of the Army’s Intelligence Department to function under the Prime Minister.

As echelons under it, the army wants to have provincial committees comprising the Chiefs of Province Police, Province Armed Police Force, Brigadier General of the NA and Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG)-level official of NID.

Although the Nepal Army has been trying to make a military ally for a decade, it has not been successful. To promote military diplomacy, the NA also proposed deploying military personnel to countries with military allies abroad. Russia, Thailand, and Belgium have also proposed to developing military allies.

At present, only the Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York and six embassies have NA personnel as military attaché. To enhance military diplomacy, the army has proposed to increase the number of military attaché in diplomatic missions.

As of now, the permanent missions in New York, the USA, India, China, UK, Pakistan and Bangladesh have NA personnel serving as military attache. Of these, the army has proposed deploying one Major each in Pakistan and Bangladesh and one Colonel each in the remaining five missions.

The report submitted to the Ministry in 2016, with the plan for a new structure in the army, had proposed an increase in the number of lieutenant generals in a bid to restructure the army.

Similarly, the army has been demanding a provision of keeping at least one Major each under the command of a Colonel in Nepal’s diplomatic missions set up in Thailand, Russia and Belgium.

NA leadership has felt it rational to have military attaches in diplomatic missions, considering Russia’s veto power, the role it can play with India and China, and the facilitation in arrangement and maintenance of the arms and ammunition of the army.

The army believes that having its representatives in the missions can help in establishing a direct military-level relationship with those countries.

The NA wants to advance its military diplomacy by stationing troops in Belgium, home to European Union’s headquarters, to ensure smooth relationships with European nations. The NA believes that the presence in Belgium can help in strengthening military relationships, especially with Europe, France and Germany.

Likewise, the NA is aware of the fact that Thailand has a strong military and is a strategic player in the Asian region. A good relationship with Thailand can be rewarding to the organization.

After the promulgation of the constitution by the Constituent Assembly in 2015, the Nepal Army was fashioned to suit the provincial structure. Earlier, it was structured as per the administrative divisions of the country.

The army does not have global practice for command structure. Although each country builds a military structure based on its priorities and needs, the military is certainly not deployed and mobilized according to the federal structure.

With the establishment of democracy, like other organizations of the state, there was a call for the restructuring of the army as well.

The government had also taken the initiative; however, as most of the reports did not agree with each other, and none of them were prepared by the army, they did not get enough attention from the NA and were not executed. The military leadership did not take ownership of the reports and did not show any interest in advancing the process.

Restructuring the organizational structure, the army was remolded under new command in 2017. After the promulgation of the constitution by the Constituent Assembly in 2015, the Nepal Army was molded with a practice similar to the provincial structure. Earlier, it was structured as per the administrative division of the country.

Then, there were five development regions, and the army had five divisions accordingly. There was structure up to the district level and it was run administratively up to that unit.

The army had reshuffled the directorate and the department at its headquarters in 2013, and the number of divisions had been increased from six to eight in 2015.

At that time, there was an in-depth discussion within the army on whether to create a war-centric structure or an appropriate federal administrative structure.

The former government had formed a five-member task force led by Defense Secretary Baman Prasad Neupane to suggest the restructuring of the army.

The task force led by Neupane had suggested restructuring the army on the basis of war-centric and strategic importance.

The fact that the Army Headquarters has been focusing on strategic issues is a significant achievement, but it needs to prove itself practically and professionally as well.

However, the then military leadership had suggested the establishment of Division Headquarters in a way that would suit the administrative structure of the seven provinces and valleys, with the conclusion that national security was internal security from Nepal’s perspective.

Eventually, without implementing Neupane’s recommendation, the army prepared an eight-division structure. After that, the divisions had been coordinating with the province government.

The report submitted to the Ministry in 2016, with the plan for a new structure in the army, had proposed an increase in the number of lieutenant generals to restructure the army.

It had suggested two options — to reduce the number of divisions and operate and direct under the command headquarters to operate under the Chief of the Army Staff.

The first option suggested by the task force was to have four lieutenant generals under the Chief of Army Staff (CoAS) and the second was to have three lieutenant generals. However, the recommendations of this report were not implemented.

Mere change in structure does not guarantee professionalism

The transformation and management of any organization over time are extremely important in themselves. The command system to ensure modernization of the Nepal Army, which has almost doubled in just four years of the decade-long armed conflict, is not all.

The structure of the military organization of the Nepal Army need not be opposite to federalism, nor can it be interpreted as disapproving federalism. Merely making structural reforms will not only improve the army’s professional development and agility.

The Nepal Army still needs a lot of restructuring in terms of its current resources, means and show of professionalism in the geographically-based structure.

As the army needs to maintain its core responsibility rather than the political and administrative division of the country, the army, which was in a difficult position due to the agreement of the previous military leadership, has now come to some professional structure.

The Nepal Army lacks adequate resources despite its number and strength. There are several issues that the army needs to pay attention to.

The fact that the Army Headquarters has been focusing on strategic issues is a significant achievement, but it needs to prove itself practically and professionally as well.

The NA, which has achieved significant administrative objectives, also needs to achieve professional success. Even now, there has been a lack of coordination among the Nepali security forces, collective planning and professional development of the security forces; and several components of national security, including national strategic vision, are in a vacuum.

Although the new concept is a step-forward policy led by the army itself, it will not achieve much unless it improves its command formation and the distribution of troops. The Nepal Army needs to accomplish a lot logistically.

The structural development of the army has not accelerated in proportion to the rapid increase of its numeral strength.

The Nepal Army also needs to wash its hands off unnecessary undertakings such as profit-making activities, and trade support role, among others.

The army should not tarnish its professional image by giving up its professionalism and national interests in the pursuit of unnecessary interests.

Contrary to its chief responsibility, the Nepal Army is damaging its professional image by undertaking tasks having financial interests and gains, unscrupulous contracts and other economic activities.

The NA has also not been able to stick to systematic accommodation, leave, etc. among others – which has remained General Thapa’s major aim to digitize. However, this has not reached the lower echelons yet. The army is becoming weak due to its deployment to unnecessary places.

Nepal has been protecting its sovereignty in its buffer status. Even now, Nepal has to deploy its troops as a common military challenge.

The challenge is still there for the army to exit from unnecessary deployments by emphasizing specialized forces such as Special Forces, Rangers, Mechanized Division, Artillery, etc.

Gaurab Shumsher Rana had devised a clandestine structure and pursued to make decisions accordingly during his tenure as CoAS. The PSOs were just formalities.

There was, however, no permanent structure, which supported the army chief to make prompt and right decisions.

The advice coming from a large number of senior officers only confused the generals. The fact that the previous Nepal Army structure – Valley Division, Brigade in zones, and battalion in the districts — was based on internal security mechanism.

As the army needs to maintain its core responsibility rather than the political and administrative divisions of the country, the army, which was in a difficult position due to the agreement of the previous military leaderships, has now come to some professional structure.

The role played by General Thapa to review and restructure the NA is commendable. However, it depends on how his successor would carry Thapa’s spirit forward. Nepal’s defense posture is not meant for the army alone but for all the stakeholders of the society.

However, there has not been enough awareness and debate on the topic. Since the army itself is a close organization and a body under the government, it is the responsibility of the government or the parliament to maintain its status and professional image.

The combat readiness and deployment of the Army are very sluggish. Most of the manpower is focused on the security of their own physical infrastructure and security outside the core duty.

The army is not necessarily at the forefront of Nepal’s internal security challenges. As the concept of Nepal Police and the Armed Police Force came up during the armed conflict, any looming security challenge could be dealt with by the APF and Nepal Police.

Nepal’s relations with its two neighbors have always posed a threat to Nepal’s security. In particular, China’s growing security structures, budget, and infrastructure in Tibet could undermine Nepal’s buffer status and, at any time, Nepal’s geopolitical balance of power.

Since China continues to make India feel more insecure, Nepal needs to create a strategic posture that can deter both countries from our land.

In particular, since Nepal has not given much importance to the concept of security of this scale or the status quo of the northern region, the situation has changed with China’s increased building of structures in Tibet.

Nepal has been protecting its sovereignty in its buffer status. Even now, Nepal has to deploy its troops to ensure that there is no security challenge. It would also be wrong to assume that Nepal is not threatened by China.

Nepal should not delay in deploying troops in a defensive posture to prevent future military maneuvers. Failure to focus on protection of Nepal’s northern region and setting up a defensive posture could jeopardize national security in the future.

Nepal should not ignore China’s growing military presence near the border with Nepal, as the capital, Kathmandu, is about 100 kilometers by road from the Chinese border in Rasuwa. Considering similar threats from both India and China, Nepal should focus on its national defense strategic military deployment.

General Thapa had envisioned and initiated the concept of a permanent structure that would function as research and internal think tank for the army.

In such deployment, Nepal must not forget the wars that it fought in history and the circumstances. Considering any possible foreign aggression, Nepal needs to deploy the Nepal Army on the basis of regional and international security dynamics, challenges and changes.

NA not yet focused on mobilization and combat formation

NA is still not fully functional and is very sluggish in terms of operations. The responsibility for unnecessary communications, multiple military structures, and internal affairs has limited the number of the army to be mobilized for its basic function.

The combat readiness and deployment of the Army are very sluggish. Most of the manpower is focused on the security of their own physical infrastructure and security outside the core duty.

For efficient operation, the number of army personnel deployed to secondary activities has to be reconsidered. Deployment of Army personnel in unnecessary locations has weakened professional capability to conduct operations, train, perform, and control.

Nepal has recently made it to the third position on the list of UN peacekeepers contributing nations. As per the government’s commitment to the UN peacekeeping mission, more than 20,000 troops have to be deployed for stand-by manpower, including training.

Unlike in other countries, the NA lacks a reserve army as it has the practice of deploying all manpower in the set structures.

Likewise, a total of 5,154 personnel have participated in the 12 missions as of June 15, 2021.

The deployment of more than eight percent of troops to protect national parks and wildlife reserves is surprising in itself.

It is obvious that with proper coordination with the local authorities and other security agencies, and through the integrated intelligence gathering, technical operations, technical surveillance methods, the protection of those places can be done with less than five percent. This shows that around three percent resource is somehow wasted here.

The command structure of the army consisted of three detachments equal to one battalion, three battalions equal to one battalion, three battalions equal to one brigade and three brigades equal to one Division.

Similarly, the number of soldiers assigned to the responsibilities of security of VIPs, national development projects, and garrison work comprises five to six percent again. This needs reconsideration as well.

Besides, unnecessary barracks and mobilization of manpower in the development work increases the cost of the project and gives space for unnecessary activism of the army. The army should come out of such issues and focus more on professional activities.

The vacancies of around 7,000 positions annually, the lack of trained army personnel, lack of coordination among the internal mechanism, the trend of allocating a remarkable number for the senior officials, etc. have made the organization very feeble in case it has to be mobilized instantly.

At present, 30 percent of the manpower, from top to bottom, of the army cannot be mobilized easily.

The number of Principal Staff Officers (PSOs) is large and far from effective. Often, its role seems to be confusing or adding dilemmas to the Chief of the Army Staff rather than helping him in executing the vision.

Instead of appointing too many people as advisors like politicians do, as put by General Thapa, the decision-making body has to be made small and effective.

General Thapa had envisioned and initiated the concept of a permanent structure that would function as the research and internal think tank for the army.

The Army still has problems with top-level management. The logistics and adjustment of the post in the army are not in harmony.

Out of the reservation quota, 20 percent has been reserved for women, 32 percent for Janajati, 28 percent for Madhesi, 15 percent for Dalit and 5 percent for people representing remote areas.

The upper echelons of the army need to be downgraded or restructured, as there are now more than a dozen senior officers in the Nepal Army.

NA structure and number

The 95,000-strong Nepal Army is still not in the army cantonment system. The command structure of the army consisted of three platoons equal to one company, three companies equal to one battalion, and three battalions equal to one Brigade.

In the lower level echelon of the Nepal Army, there will be up to 11 soldiers led by a corporal, up to 36-member platoon under the command of a lieutenant, up to 250 company under the command of a Major, up to 800 battalions under the command of a Lieutenant Colonel, and up to 3,000-member brigade under the command of Brigadier General.

Likewise, a Major General used to command a division of up to 12,000 army personnel. According to the current structure of the Nepal Army, 3 sections equal to 1 platoon, 3 platoons equal to one company, 3 companies equal to 1 battalion, 3 battalions equal to brigade, 3 brigades equal to 1 division.

There are also other support units and combat civil support units in the Brigade and Division. The Nepal Army, like other institutions in Nepal, has started the practice of inclusive participation.

During the Maoist insurgency, the NA recruited women only in the technical field, but since 2004, women have been recruited in combat duty as well. Currently, there are more than 5,000 women in the Nepal Army.

Considering the ethnic composition of the NA, it has 42.1 percent Chhetris, 8.7 percent Brahmin, 8.3 percent Magar, 5.7 percent Newar, 4.9 percent Tamang, more than 3 percent each from the Kami, Tharu, Thakuri communities, and more than 2 percent from the Gurung and Rai communities.

The rest of the caste has a negligible presence in the NA. The issue of restructuring and inclusion in the NA was raised vehemently after 2006.

Reservation in army recruitment is a preconceived notion that the competitiveness of voluntary recruitment is declining in the name of inclusion.

Even though the then government had agreed with the Madhesi parties for a mass inclusion of Madhesis in the NA, the army had publicly opposed the idea.

The NA is still adamant about not recruiting on the basis of caste, even as the inclusive norms have been gradually implemented.

According to the policy that has been made mandatory after the formation of an Act after the political change in 2006, the army has a provision of up to 45 percent reservation quota in it.

Out of the reservation quota, 20 percent has been reserved for women, 32 percent for Janajati, 28 percent for Madhesi, 15 percent for Dalit and 5 percent for people representing remote areas.

However, the number of individuals and aspirants from the above-mentioned provisions and quotas has not been quite low at the upper level.

Reservation in army recruitment is a preconceived notion that the competitiveness of voluntary recruitment is declining in the name of inclusion.

Among the 216 castes in the army, 80 castes have one each representation, two each from 27 castes, three each from 11 castes, four each from seven castes, 186 castes below 100, and below one thousand from 202 different castes.

Comment