NEW DELHI: Kangana Ranaut in and as Manikarnika, the queen of Jhansi, delivers exactly what was promised: a high-decibel, high-on-rhetoric hagiography of a queen who fought for her people and her land, till her last breath. There is not a single complex thought in this nearly three-hour movie, which runs out of steam in the third act because it needs to repeat its battle scenes ad nauseam to fill up the time till the end. It’s all kept deliberately simple (in some places, even simplistic), linear, first this happened, then this happened, and then. We the viewers have to do no work to get with the movie’s plan: we just have to sit back, go with the flow, flabby and clunky in bits, and admire Ranaut blazing on the screen.

Which she does, with such fierceness and gumption that you cannot take your eyes off her, especially when she is in full stride. She embodies the spirit of a very special young woman married into a ‘rajwada’, to an effeminate princely type (Sengupta), catapulted into the throne, not because she wants it, but because she is the only real man among the men who surround her.

Naturally, no other actor gets as much screen time as her: after a while it looks as if she is in practically every scene, as Manikarnika : The Queen Of Jhansi takes us from the ghats of Manikarnika in Banaras, to Bithoor where Manu’s prowess with words and swords catches the eye of the man (Kharbanda) responsible for her marriage and make-over as Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi.

The filmmakers (with Ranaut getting a co-director credit) have the usual caveat of the film taking creative liberties with the facts. So we don’t really have to worry our heads about whether all the stuff unfolding on screen happened or not. We are given a glimpse of palace intrigues where a black-hearted cousin (Ayyub) hankers for the throne, as Ranaut’s Laxmi, dripping more brocade and baubles to sink a thousand thrones, plays the part of wife and mother. It’s all very trying, this prelude to the real act, filled with Ranaut made up to the hilt (did they really have false eyelashes in 1830?) romancing, dancing, singing with ‘sakhis’ in age-old Bollywood style.

The film does make a brief stab at showing us how Laxmi created an army of women (and giving the film its chance to sling in a rousing ‘action’ song as they flash blades and swirl and twirl). Other characters come and go. There’s the faithful Ghaus baba (Denzongpa), Tantya Tope (Kulkarni), and a whole series of bumbling Englishmen, who make the mistake of thinking that Rani will be a weak puppet, just like her neighbouring princes who have keeled over at the slightest hint of British aggression, and are living on their pensions.

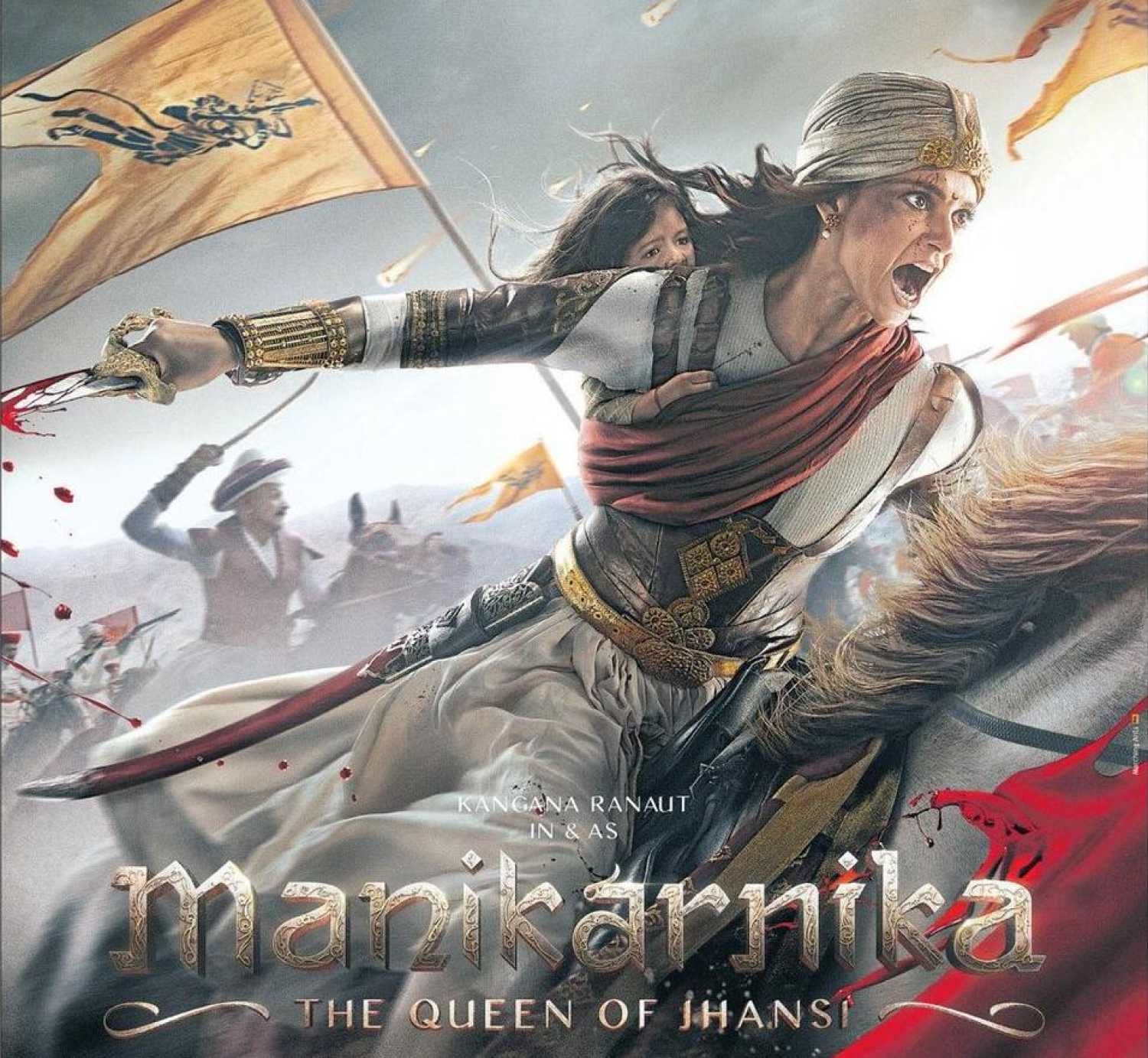

The 1857 Mutiny pops up too, and we get a glimpse of the ‘greased cartridges’ and the ‘chhaavni of Meerut’ and the ‘rebel’ armies falling by the wayside. But we know it’s all window dressing, a backdrop for the Rani to rise, and show us what bravery and valour and patriotism is all about. Ranaut in full battle mode is a sight to behold: harnessed, charged up, tearing and slashing through the rows of ‘dushman’ soldiers, all snarly and bloody. The battle scenes are impressive: lots of ‘josh’ right there.

The film skews, naturally, towards the ruling establishment in its exhortation of what nationalism means (there’s a great Scindia-Gwalior dig in there). A calf is saved from slaughter. Dialogues abound about ‘Bharat Mata’ and its ‘betis’, and a priceless one goes like this: ‘jab beti uth khadi hoti hai toh jeet badi hoti hai’. Claptrap, yes. But also clap clap.

As promised, Manikarnika does tick all the nationalistic boxes. It is getting a perfectly-timed Republic Day release. And there are plenty of eye-roll moments as it chases the red-faced Brits, and raises the flag. It may have been Jhansi, but it is clearly a prelude to the ‘tiranga’. But what keeps us with the film is Rani Ranaut, who in her best moments, owns her part, the narrative, and the screen.

(Agencies)

Comment