KATHMANDU: On the campaign trail, Rabi Lamichhane often told supporters that his only weapon in politics is integrity.

The former television host, who stormed into parliament in 2022 with promises to clean up Nepal’s corrupt politics, built his reputation on fiery speeches and relentless exposure of wrongdoing. Yet today, as he sits in judicial custody in Bhairahawa on charges linked to cooperative fraud, Lamichhane’s integrity is under unprecedented scrutiny.

Beyond the courtroom, another controversy continues to shadow his political career: his infamous attack on Nepal’s media, known as the “12 bhai” episode. For critics, it crystallized a populist leader’s intolerance of scrutiny.

For supporters, however, it reflected a man pushed to the edge by entrenched elites determined to block his rise. Either way, the dispute has left a lasting mark on the relationship between politics and the press in Nepal.

Meteoric rise from TV anchor to political disruptor

Lamichhane, born in Kathmandu in 1975, was not a traditional politician. His early years were spent in journalism, where he gained national prominence as a television presenter. In 2013, he grabbed global headlines by hosting a marathon 60-hour talk show that earned a Guinness World Record. His high-energy broadcasts, often blending investigative zeal with moral outrage, resonated with younger Nepalis frustrated with corruption, unemployment, and stagnant governance.

After years in the United States, Lamichhane returned to Nepal in the mid-2010s. A decade later he became managing director of Galaxy 4K Television. But his ambitions stretched beyond the newsroom.

In 2022, months before national elections, he founded the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP). Riding a wave of anti-establishment sentiment, the party shocked Nepal’s political establishment by finishing fourth in the polls, securing 1.1 million votes.

Lamichhane himself won decisively in Chitwan, becoming Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister. For a moment, he seemed to embody the promise of generational change in Nepal’s democracy.

Triumph to turbulence

His tenure as Home Minister, however, was short-lived. In January 2023, the Supreme Court ruled that Lamichhane had failed to properly regain his Nepali citizenship after renouncing his U.S. passport, invalidating both his parliamentary seat and ministerial post. Though he quickly reacquired Nepali citizenship and won re-election with an even larger mandate, the controversy over his dual passports cast a long shadow.

Personal matters, too, became political fodder. His divorce in the United States, his second marriage in Nepal, and rumors about his family life were repeatedly dredged up by opponents and amplified by a curious public. In Nepal’s conservative society, where personal morality is often conflated with political credibility, these details complicated his image as a reformist outsider.

Yet nothing tarnished his reputation with the media quite like the “12 bhai” outburst.

‘12 bhai’ controversy

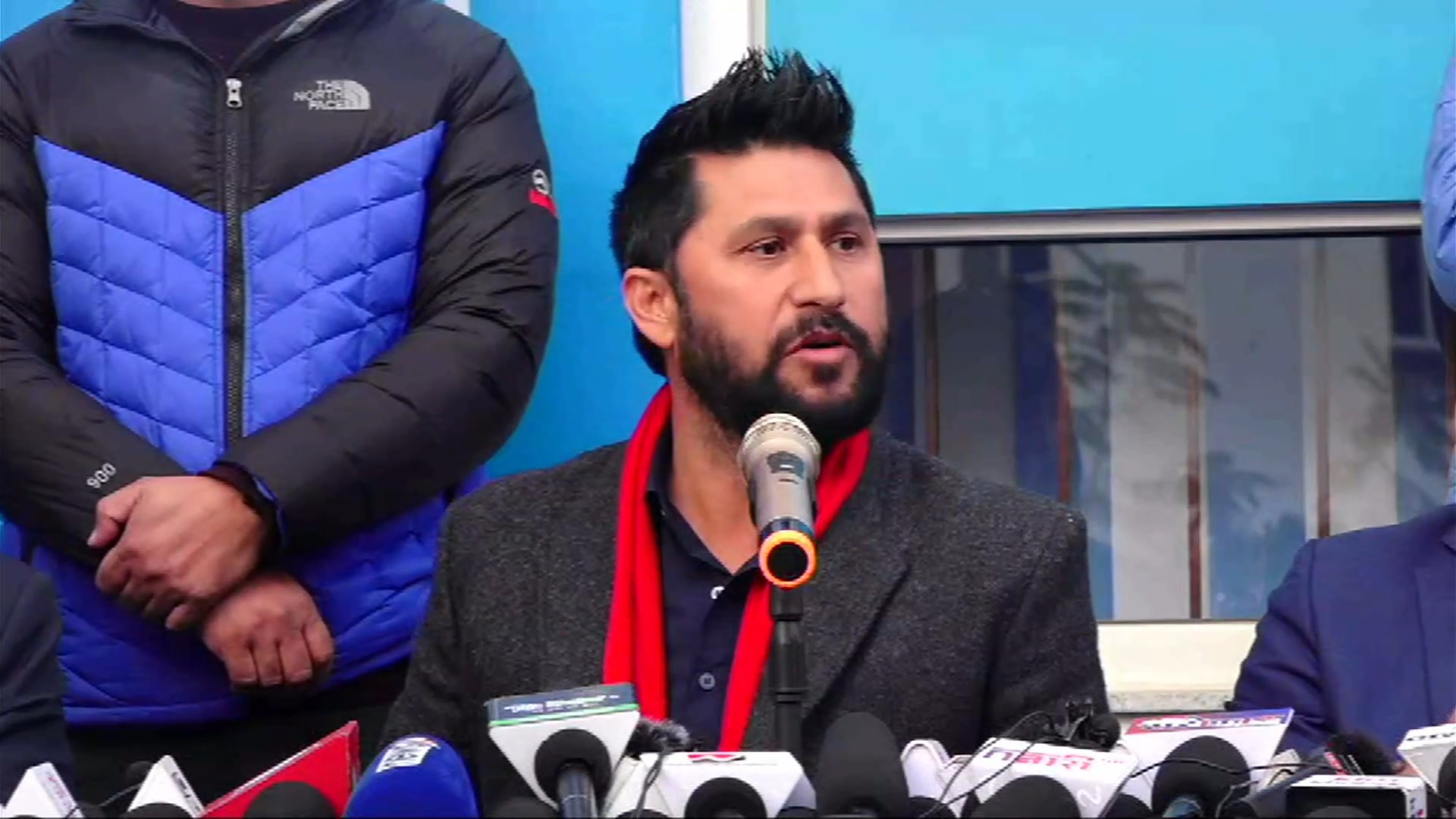

Frustrated by what he saw as unfair coverage after losing his ministerial seat, Lamichhane convened a press conference in early 2023. Instead of addressing policy or legal issues, he launched into a blistering attack on the press. Naming senior editors and accusing them of conspiring over drinks to tarnish his image, he dubbed them the “12 bhai’, a clique allegedly plotting against him.

His language was sharp, personal, and often threatening. He warned that he would expose journalists’ private lives, even hinting at surrounding newspaper offices if negative stories continued.

The remarks triggered widespread outrage. Editors’ associations accused him of undermining press freedom. Civil society groups warned that such rhetoric, coming from a powerful figure, could fuel harassment and violence against journalists.

Although Lamichhane later apologized, admitting that he had been emotional and crossed a line, the damage was lasting. The phrase “12 bhai” became shorthand for his combative approach to criticism, and a symbol of the growing friction between populist leaders and independent media.

Populism versus accountability

Lamichhane’s clash with the media reflects a broader global pattern: populist leaders framing independent institutions as enemies of the people. His supporters, many of them young and disillusioned with traditional parties, often echo his narrative that the press is part of a corrupt establishment bent on preserving privilege.

But media scholars argue that such hostility undermines democracy. “A free press is not perfect, but it is essential,” one Kathmandu-based analyst said. “When politicians paint the media as conspirators rather than watchdogs, it weakens institutions and emboldens authoritarian tendencies.”

In Nepal, where the press has historically played a crucial role in holding governments accountable , from exposing corruption to covering civil conflict, Lamichhane’s attacks were particularly alarming. His words also appeared to embolden leaders from established parties, such as KP Sharma Oli, who have often bristled at critical reporting.

The paradox of ‘new politics’

Rastriya Swatantra Party was born out of frustration with Nepal’s traditional political class, accused of corruption, nepotism, and cynicism. Lamichhane’s promise was that RSP would be different, youthful, transparent, accountable.

Yet his own behavior has often mirrored the very practices he condemned. His threats against journalists echoed the intolerance shown by older leaders. His opaque handling of financial allegations, now at the center of cooperative fraud cases, clashed with his anti-corruption rhetoric.

The paradox raises a difficult question: can a movement built on anger at old politics succeed if its leaders adopt the same authoritarian impulses?

Beyond the courtroom

For now, Lamichhane’s immediate future hinges on the courts. Judges in Rupandehi have already ordered him into judicial custody as investigations into cooperative fraud deepen. His legal troubles may decide whether he can continue leading RSP or whether the party will need new leadership to sustain its momentum.

But the larger test lies outside courtrooms and prisons: whether Lamichhane and his party can evolve into a force that embraces, rather than resists, democratic accountability. For a party positioning itself as Nepal’s alternative, the stakes are high.

If Lamichhane continues to treat the press as an adversary, he risks repeating the cycle of distrust and hostility that has long undermined governance in Nepal. If he can accept criticism as part of public life, he might still fulfill his promise of being a genuine disruptor.

Show goes on

In Bhairahawa prison, Lamichhane reportedly spends his days strategizing, reading, and assuring followers that he will return stronger. His supporters still pack RSP rallies, convinced that their leader is the victim of an orchestrated takedown. His critics, meanwhile, see his detention as overdue accountability for a man who thrived on bending rules.

Whatever the verdict in court, the “12 bhai” controversy ensures that Lamichhane’s legacy will not be judged only on election results or cabinet posts. It will also be measured by how he treated Nepal’s press, whether he saw it as a democratic safeguard or an obstacle to be crushed.

For a country still testing the durability of its young republic, the answer may say as much about Nepal’s future as it does about Rabi Lamichhane’s.

Comment