Susuwa Lilim Yakthunghang: The spiritual knowledge of the Yakthung Limbu people is known as Mundhum. The rituals performed by the Limbu spiritual leaders—Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema—from birth to death are collectively referred to as Mundhum. According to Mundhum, the Yakthung Limbus are descendants of Susuwa Lilim Yakthunghang.

The first human in Mundhum is Mujingna Kheyongna, who conceived through the wind. Her son is called the “children of wind and air,” known as Susuweng Lalaweng.

As time passed, the term Susuweng Lalaweng evolved into Susuwa Lilim. After the descendants of Susuwa Lilim began farming and settling communities, they came to be known as Susuwa Lilim Yakthunghang.

In the 18th century, the Yakthung Limbu scholar, led by Sirijunga Sing Thebe, introduced a script in the Yakthung Limbu language. This script is known as the Sirijunga script. In the writings found in this script, Sirijunga referred to himself as a descendant of Susuwa Lilim Yakthunghang.

In the Hodgson Collection, volume 84, page 218, writings by Sirijunga and his disciples explain that Yakhak or Yakthung means Bhainphatta, which translates to “one born from the earth.”

In the collected works of Hodgson, Volume 85, page 44, documents mentioning “Dash Lungbung” (Ten Lungbung) have been discovered.

According to Mundhum, Susuweng Lalaweng had four wives: Thosu Mukkumlungma, Yosu Fiyamlungma, Turere Tugeyangma, and Tusanglima.

From the union of Mukkumlungma and Fiyamlungma, one son and one daughter, Suchhuru Suhampheba and Tetlara Lahadongna, were born.

Similarly, from the union of Tugeyangma and Tusanglima, two sons, Thosu Sangdangkhwa and Yosu Lingdangkhwa, were born.

Currently, in Lungdhung of Lelep, the children of Susuweng Lalaweng, Suchhuru Suhampheba, and Tetlara Lahadongna, are engaged in an illicit relationship.

This caused conflict and epidemics to spread in the village. They were punished by the Lungbongba Khambongba, considered the primordial settlers, who were described as those who sheltered under the mushrooms, struck fern, butchered lice, and rested loads on goat’s manure.

The punishment involved separating their offspring by placing them on a bamboo Malingo/Arundinaria pantingia sieve.

The children who remained on the upper side of the sieve were assigned to their father, Suchhuru Suhampheba.

These children became known as Sudukyu Khedukyu Fedangma, Phungjiri Phungappo Fedangma, Thiri Wasophungwa Fedangma, Singsara Theyapmi Fedangma, Mugaplung Khagaplung Samba, Nenjiri Nempatthang Samba, Sazuwet Mudangwet Samba, Singdumaing Fetlaing Samba, and Nanggetcho Phulum Samba. Suchhuru Suhampheba and his descendants were exiled to Muringla Kharingla.

Subsequently, Suchhuru Suhampheba became known as Sodungen Lepmuhang, and they were referred to as Pegi Fangsam.

The children who fell to the lower side of the sieve were assigned to their mother, Tetlara Lahadongna.

These children included Tappeso Lummahang, Sagimso Sangmihang, Niyara Thokchanghang, Lalaso Pangbohang, Furupso Thejanghang, Khechhuwet Uppanhang, Sa:undu Unduhang, and Sechhere Senihang.

They were collectively known as Sawa Yethang or the eight enlightened noblemen. Tetlara Lahadongna and her eight children remained in Sango Kopirakma and she is named Thirilung Thamdetlungma.

In the middle of the sieve, one daughter, Samedhung Yepmedhung, got stuck. She later became the master Paikwa Maikwa Sam of Sibhak Yami or Yeba/Yema.

The role of the Pegi Fangsam was to call upon spirits and perform healing rituals to address sickness, famine, epidemics, and natural calamities in the Sawa Yethang village.

However, as the village frequently suffered from spirit-related afflictions and the Fedangmas and Sambas alone could not contain them, Sodungen Lepmuhang sent powerful Yeba/Yema, such as Yabhokko Yasiring, to Sawa Yethang Pangbhe.

In this way, the descendants of Susuweng Lalaweng were punished by the Lungbongba Khambongba or the indigenous settlers.

As time passed, these settlers later became known as the respected figures of society, called Tuttu Tumyang.

Following this, justice in the Sawa Yethang society was dispensed by the Tuttu Tumyang, while the primary responsibility of Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema was to protect the Sawa Yethang people.

All the Mundhumic places mentioned above are located in Lelep of Faktanglung Rural Municipality in the present-day Taplejung district.

Limbu and Limbuwan:

The primary role of Tumyangs was to deliver justice to the Sawa Yethang. Tumyang would convene assemblies referred to as Chumlung in the village to resolve disputes.

They would swear oaths by touching dubo/cynodon dactylon grass and embedding stones in the ground as a symbolic act of justice.

In Yakthung Limbu language, Mundhum is commonly referred to as “Samjik MundhumÆ or æMundhum Habek.” Here, “Sam” means soul, and “Jik” refers to parts of the soul residing in nature.

In the Limbu language, stones are called Lung, and dubo grass is called Samyo.

The act of swearing an oath by touching dubo grass and pledging not to repeat a mistake was called Samyoklung.

After this, stones were buried in the ground as evidence and witnesses to the resolution. These embedded stones were referred to as Lungbung.

In the collected works of Hodgson, Volume 85, page 44, documents mentioning “Dash Lungbung” (Ten Lungbung) have been discovered.

Lungbung in Chinabung, Libang, Taplejung

It appears that different groups of Limbus in various places resolved disputes by embedding stones, leading them to be referred to as Dash Lungbung.

Similarly, a document digitized by Mukunda Luintel on the eap.bl.uk link mentions a paper from the year 1824 VS related words like Das Limbu are also recorded.

This suggests that after the Yakthungs came into contact with the Sen kings, the Sens addressed the Limbus, who were embedding stones Lungbung for justice, as Lungbung, which later evolved into the term æLimbu”.

When the Shah kings imposed taxes based on land units measured in Ana, the term “Limbuwan” came into existence.

Even today, these buried stones can still be found in villages. These Lungbung, or stone markers, symbolize the governance and administration of the Yakthung Limbu in the past.

Stones, or Lung, hold significant importance in the Limbu community. Stones embedded in places of worship for deities are called Kamyanglung.

Stones embedded to claim land ownership are known as Yopalung. Stones placed to demarcate boundaries are called Indolung.

Stones used to convene courts are referred to as Chumlung. Stones embedded as evidence after providing justice are called Lungbung.

Stones embedded after fulfilling vows are called Cho?lung. Finally, stones placed over graves are referred to as Sutlung.

The Role of Soul and Spirit in Mundhum:

Mundhum is not just a chant for healing but also a history of societal development.

The ancestors of the Limbu people, in their hunting-gathering journey to develop their families and society, preserved their experiences of confronting nature.

For instance, the soul of Taagera Ningwaphuma, the creator of the universe, is believed to manifest as Sammang or as the divine spirit Yuma .

These experiences continue to be practiced today by Fedangmas, Sambas, Yebas/Yemas through rituals performed from birth to death, and the elders or leaders in villages—Tuttu Tumyang—also invoke Mundhum as customary law while making judgments or advocating for justice.

Even today, Tuttu Tumyang, Fedangmas, Sambas, and Yebas/Yemas have their presence in villages.

In Yakthung Limbu language, Mundhum is commonly referred to as “Samjik MundhumÆ or æMundhum Habek.” Here, “Sam” means soul, and “Jik” refers to parts of the soul residing in nature.

“Habo” means gums or teeth, and the action of forming words through Habo is “Habek.”

Similarly, “Mumma” means to move or vibrate, while “Thukma” refers to invoking and communicating with the soul.

The Fedangmas, Sambas, and Yebas/Yemas invoke the soul into their bodies, channel it, and then narrate Mundhum through this connection.

The Limbu people believe that the entire nature is influenced by the spirits or “Sam” of their ancestors.

These spirits reside in various natural elements such as rivers, lakes, mountains, caves, trees, birds, and animals.

For instance, when they call upon their origin Mangenna Yok, they believe that the first ancestor, starting from the primal ancestor Mingh-sra, resides in the sacred cave or Mangenna Yok.

Therefore, such caves or Mangenna Yok are considered sacred. Similarly, if someone drowns in water, Yeba performs rituals in the water itself to confine or pacify the troubled soul.

For example, when Yebas/Yemas summons birds or animals and addresses them with phrases like “Samu E Sire Lakfekse,” they understand that even eagles embody spirits.

In essence, the Limbu people revere their ancestors as deities or Mang. These ancestors are believed to have played a vital role in the creation of the universe and human life.

In the Yakthung Limbu community, there is a deep-rooted tradition that Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema are born with an innate knowledge of Mundhum and healing wisdom.

In Limbu belief, though the physical body perishes, the soul does not die. The soul descends into descendants as Sammang or divine spirits.

For instance, the soul of Taagera Ningwaphuma, the creator of the universe, is believed to manifest as Sammang or as the divine spirit Yuma .

Yuma Sammang is regarded by the Limbu as a divine ancestor who taught them to recognize seeds, practice farming, cultivate cotton, weave thread, and make and wear clothes. She is honored as a protector and divinity ancestor.

Deities like Taagera Ningwaphuma and Porokmi Yamphami Mang are seen as omnipotent, omnipresent, benevolent, and protective.

However, if divinities or Sammangs are displeased, they can become destructive.

Similarly, the Kui-Kutap Mang or nature divinities hold distinct significance. If they are not appeased, they are believed to bring misfortune.

The life force of living people is called “Hangsam.” The souls of those who pass away peacefully are called “Thawa Sam.” On the other hand, the souls of those who die unnaturally or in unfortunate circumstances are known as “Sisam.”

For example, the souls of those who die by falling ( Idhuk Samsogha), women who die during childbirth (Khappura Sugup), those whose bodies are touched by animals post-death (Lechham), or children who die before growing teeth (Sasik Yangdang) are all considered Sisam. Such spirits must be appeased and pacified.

If not, they are believed to bring suffering, illnesses, floods, landslides, droughts, famines, and epidemics.

Therefore, the rituals performed to appease Mang, Sammang, and Spirits are collectively known as Mundhum.

Scholars of Mundhum:

Tuttu Tumyang, Fedangma, Samba, Yeba/Yema are considered the knowledge bearers of Mundhum. Tumyangs primarily engage in judicial duties. Fedangma, Samba, Yeba/Yema perform ritualistic duties.

They adorn themselves with crosses made from the feathers of birds like the myna lige wado and the danphe-monal/lophosphoros/ samdangwa yamlaakwa) featherdresses terep wasang. Around their waists, they tie bells siring pange.

In the Limbu community, before birth, a ritual called Sappok Chomen (a prayer for the unborn) is performed.

After that, birth (Sawanchingma) and death (Yagu Changsima) rituals are carried out. After death, rituals separate the living soul (Hangsam) and the dead spirit (Thawasam), such as the Murum Ina Semma ritual.

In the Yakthung Limbu community, there is a deep-rooted tradition that Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema are born with an innate knowledge of Mundhum and healing wisdom.

These individuals inherit all their rituals and knowledge directly from their teachers (Paaikwa Maikwa Sam). When they visit their disciples (Sa: pendi) for endowment (Ya:bhacha), they guide them by walking with them, dancing, making them perform Mundhum recitations, teaching them all the procedures and practices (Timsingma), and then sending them off (Ya:thare Yemma).

Not only in judicial activities but also in social rituals, Tumyangs play a significant role. While performing rituals, when Fedangmas, Sambas, and Yebas/Yemas are invited [faksara lamlak], the tasks they perform are monitored by the Tuttu Tumyang.

Tumyangs are also responsible for hosting guests and relatives (Henamoma) and performing rituals to ward off curses and ill wishes (Manghup Bademma).

During the rituals performed by Fedangmas, a specific area inside the house is smeared with red clay, where incense lagun, coal mitak, banana leaves [Tetla Laso], and sacred rice grains [Tumphung Seri Sya] are placed on a ritual seat.

Saptok [bamboo sticks cutting round] and Peheṅng [bambosticks cutting shaped] are filled with millet beer [tongba] placed.

For the nature divinities outside the house, small mound stones Kamyanglung are set on the edges of fields and farmland, with sacred tree twigs chamsing/sangasing established.

For Sambas, a single Patlekatus/ castanopsis hystrix/khhechhingse wooden pillar (Khamlung Kesing) while for Yebas and Yemas, two wooden pillars (Yege Sing/Yagrang Sing) are erected to mark the altar.

Along the altar, a drum chyabrung/niyara hongsing ke is placed horizontally and a bamboo basket dhobe/lumbhu is place on top.

There is also decorated Tongsing mohola/ch?op/tongsing yukna/yangdang symbolizing the living soul and the spirit of the dead.

Tumyangs are often seen wearing white cloth turbans pagas during court gatherings.

Fedangmas do not have such distinct attire. The clothing of Sambas and Yebas is almost identical.

Yebas wear traditional clothes made of cotton, such as bhota-mekhli/tendham-simbo.

The ancestral spirits, invoking the sky and the earth, recite the Mundhum. They name mountains, hills, caves, ponds, streams, plants, and animals, forging a profound connection between the Limbu community and nature.

They adorn themselves with crosses made from the feathers of birds like the myna lige wado and the danphe-monal/lophosphoros/ samdangwa yamlaakwa) featherdresses terep wasang. Around their waists, they tie bells siring pange.

On their backs, they carry a cross jabe bag (omlari pettari sukwa) made of orchid flower stems.

They hang wild boar tusks sera keng on the bag, keeping them crossed. Yebas also wear necklaces made of snake bones singdum asek pona, claybeads khambrakma, stone beads lungbrakma, and colorful red and yellow earthen beads pangwari panchhe.

Performing ritual by Samba Rudra Bahadur Tilling in Faktanglung/Kumbhakarna/Junuu

They also create amulets made of various herbal like bikhma aconite and talismans using the genital organ of a boar.

They also incorporate items like stone light wobholung and small spikes of the porcupine khamlung aibukma on altar. The attire of the Yeba/Yema is called Yesama.

Yeba/Yema wears a horizontal cross feather while the Samba wears a vertical one. Additionally, the sacred pouch jabe jhola is always carried in a vertical position.

In fact, Fedangmas, Sambas, and Yeba/Yemas made mesmerizing and fierce appearances through their unique attire.

Accompanied by the rhythmic sounds of brass plates Samling Chethya, ringing bells, and imitations of animals and birds, they dance and enter a trance-like state to sanctify the sacred space.

However, earlier foreign writers who explored Limbu language, history, and culture, such as William Kirkpatrick (1811), Francis Buchanan Hamilton (1819), and Brian Hodgson (1880), did not use the term “Shaman.” Archibald Campbell (1855) and Joseph Dalton Hooker (1855) referred to Limbu Fedangmas as “Fedangbo.”

The ancestral spirits, invoking the sky and the earth, recite the Mundhum. They name mountains, hills, caves, ponds, streams, plants, and animals, forging a profound connection between the Limbu community and nature.

Through these rituals, they call upon the experiences of the Limbu people, rejuvenating their livelihoods, social development, environmental knowledge, and energy.

In this state of entrancement, they transform consciousness, invite spirits into the body, and communicate with them.

Acting as mediators between the physical and spiritual worlds, they offer psychological insight to dispel jealousy, hatred, curses, suffering, illness, mental imbalances, and negative energies from homes, families, and society. This process fosters peace, harmony, longevity, and prosperity within the lineage, family, and the broader community.

In essence, Mundhum is not just a matter of faith and belief but also encompasses biological knowledge, customary laws, craftsmanship, labor, and production. These are sacred and indispensable rituals for the Limbu people, integral to their way of life.

Shaman versus Fangsam:

The word “Shaman” originates from the Tungusic people of the Evenki family residing in Mongolia and Siberia.

The term “Shaman” means “to know” or “to take action.” Its first recorded use dates back to the 17th century, when Proto-Pop Avakum of the Kazan Cathedral mentioned it.

Avakum, exiled to the border of Siberia and Mongolia due to his dissent against the reforms imposed by Tsarist rulers and religious authorities, encountered Tungusic Shamans, particularly in matters of prophecy.

While writing his accounts in Russian language, the word æShamanÆ popularized across Europe.

In the process of societal development, initially, only Fedangma and Samba were referred to as Pegi Fangsam, but later, Fangsam was also used to refer to Yeba and Yema. French researcher Philippe Sagant referred to Limbu Fangsam; as “Shaman.” Sagant visited Libang village in the Taplejung district twice between 1966 and 1971, staying with Fedangma Angekema of Tumpangphe locality.

A buffalo used its horns to clear the way, and as a mark of respect for their ancestors’ protector, the Fenduwa Madens refrain from eating buffalo.

His research extended as far as Tokpegola, near Tibet. Sagant’s ethnographic works focused on Yakthung Limbu priests, particularly Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema.

His findings were first published in 1976 and later included in a collection titled Becoming a Priest: Ethnographic Notes by John T. Hitchcock and Rex L. Jones in 1996.

The English translation of his French work, The Dozing Shaman: The Limbus of Eastern Nepal, was published in 1996.

Both Sagant and co-authors Rex L. Jones and Shirley Kurz Jones referred to Limbu Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema as “Shaman.”

However, earlier foreign writers who explored Limbu language, history, and culture, such as William Kirkpatrick (1811), Francis Buchanan Hamilton (1819), and Brian Hodgson (1880), did not use the term “Shaman.” Archibald Campbell (1855) and Joseph Dalton Hooker (1855) referred to Limbu Fedangmas as “Fedangbo.”

Similarly, Eden Vansittart (1896) used terms like “Fedangma, Samba, Yepmundhum” to describe them.

Comparing Fangsam to Tungusic Shmans is inappropriate. No culture is inherently superior or inferior; every culture must be understood within its unique historical and social context. Evaluating a culture through external standards is unjustified.

The Mundhum of the Limbus perceives nature as sacred and alive, recognizing consciousness in every element—plants, animals, rivers, mountains, the sun, moon, and sky.

Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema act as bridges between the human world and the natural/spiritual realms. Their teachings remind humanity to reconnect with nature, which could offer solutions to environmental crises.

Mundhum can be compared to Native American indigenous cultures, such as the concept of Totem.

A totem symbolizes ancestral and collective identity, often associated with animals or natural elements.

In the Limbu language, a Totem could be referred to as Kugusing. For instance, the Fenduwa Maden Limbu clan abstains from eating buffalo meat.

Those who follow traditions and rituals based on Mundhum offer the departed spirits Thawasam on the same day the deceased is buried, through a ritual called Samsama.

According to Mundhum, Yuma Sammang and her children were once blocked by a pond called Welaso Fulaso.

A buffalo used its horns to clear the way, and as a mark of respect for their ancestors’ protector, the Fenduwa Madens refrain from eating buffalo.

Similarly, Totem or Kugusing serve as guides for protection and societal values.

However, it is essential to preserve the unique identity of cultural terms. For example, Kugusing should remain Kugusing, and Totem should remain Totem.

Referring to Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema as “Shaman” risks erasing their original terms.

Another example worth mentioning is the Pacific island concept of Taboo, which signifies prohibition. Taboo enforce societal norms, regulate traditional lifestyles, and uphold cultural values through dietary restrictions, rituals, and sacred spaces. Taboo-like practices also contribute to environmental balance.

For example, the Khewa Limbu clan abstains from consuming birds, which indirectly helps preserve ecological balance. In the Limbu language, Taboo could be translated as “Chin.”

Mundhum is essentially an epistemology—a way of acquiring knowledge. According to Mundhum, nature and humanity’s relationship with it are the ultimate sources of knowledge.

Mundhum also serves as a rhetorical tradition, using language as a medium to pass knowledge across generations.

Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema transfer this knowledge by reciting, singing, and dramatizing Mundhum in an engaging and theatrical manner, often accompanied by their helpers Mangwaneba, Sanglanggoba, and Yegapchi, who are enshrined at sacred sites Than/Sangbhe.

Attainment of Cho?lung:

The Yakthung Limbu people refer to their place of origin as Thamalung. The term Mingsra denotes the first ancestor.

After the ancestors separated, the term Passing Padang is used for the succeeding generations.

The land where the ancestors settled and built their livelihood is known as Fechhuwa Yok, while Nahangma Yok is associated with honor and dignity.

If a certain ancestor from a Yok becomes renowned for bravery, other Limbu clans may affiliate with that Yok.

The place where ancestors Thawasam are honored and their spirits appeased is called Sam Samaten.

Yuma Sammang taught her descendants how to live by planting seeds around various lakes and rivers, including Singsaden, Sodhung Worok/Tokpegola, Palung Malung Worok, Tiptala , and the shores of lakes such as Wetlaso Phulaso.

Those who follow traditions and rituals based on Mundhum offer the departed spirits Thawasam on the same day the deceased is buried, through a ritual called Samsama.

However, those who also follow Hindu traditions observe a Samdakhong ritual. In such cases, the ancestors are appeased only on the day of purification.

The Thosumali (those from Miwakhola, Maiwakhola, Tamor Khola, and Kabeli Khola regions) Limbu clans perform the Samsama ritual.

Meanwhile, the Yosumali (those from Athrai, Fedap, Chaubise, Panthare, Chathare, and the areas across Kaweli) Limbu clans observe the Samdakhong ritual.

When worshipping pregnant women’s wombs, a ritual called Sappok Chomen is performed at a place called Samlamaten.

The Thosumali Limbus usually go to the Miwakhola Yumikma Worak Pokhari lake, while the Yosumali Limbus travel to the tri-junction Seghek Surungma at the confluence of the Mouwakhola, Tamorkhola, and Sagokmari Khola in Chathar Okhre for this ritual.

The search or acquisition of knowledge by Yakthung Limbu is Cho?lung. In the past, our ancestors had to face nature to survive. Great events took place.

Those experiences are still present in the form of cultural knowledge. The process of revitalizing such great achievements is called Cho?lung Changma Ritual.

According to Mundhum, in the past, Porokmi Ymphami created the sun, moon, stones, soil, and humans, and scattered the seeds of food for humanity. However, they did not grow.

Therefore, Porokmi Yamphami requested a large stone from the people of Faksera Tigenjong of Iwa Hara.

He agreed that if he failed to bring short put of the stone, he would accept death.

Porokmi then went to Iwa Hara and threw the shot put in the Ladok Namdok Surungma, which was in the sky.

The stone also hit the shoulders of the Fktanglung/Kumbhakarna Himals. It caused rainfall in Sakholung Khongwana Tembé.

In reality, this event was a great achievement for Yakthung Limbu in facing nature and surviving.

Revitalizing such great achievements is the Cho?lung Changma ritual. By performing Cho?lung Changma, the Limbu people gain good health, long life, and prosperity.

Yuma Sammang taught Yuma Sammang taught her descendants how to live by planting seeds around various lakes, rivers, mountains, and caves including Singsaden, Sodhung Worok/Tokpegola, Palung Malung Worok, Tiptala , and the shores of lakes such as Wetlaso Phu?laso and mountain like Muktibung/Pathivara.

This marks the beginning of Yakthung civilization. When the water levels in lakes, rivers, and streams decrease or snow melts from the mountains, the Fedangma, Samba, and Yeba/Yema perform Mundhum and fill the lakes with water.

They place fish in the streams and revive the lakes by planting jatamasi/pangbo?phung/nardostachys and padamchal/kenjofung/rheum austral flowers, thus awakening Cho?lung.

Yuma Sammang also introduced seeds to the people of Linghim and she guided Sa:ogehang and Sigara Yavungkekna to grow crops.

Mukumlungma and Fiyamlungma, people learned to cultivate silkworms, grow them, harvest the threads, and weave clothes, which they wore with pride.

This is why there is mention of Cho?lung awakening when the young people weave and make clothes.

The youths of Feyaari Chechengba created iron-cutting tools, established boundaries, or invented iron weapons.

blossoming Jatamasi/Pangbo Kunataphung/Nardostachys in Tokpegola, Taplejung

This is why Feyaari Chechengba is called the Cho?lung of the young people. The elders of the Limbu community began providing justice by raising stone walls, building resting places, digging stones, and offering blessings in Sangsanglung Khallonlung.

Sirijanga and Pratap Singh Shah seem to be contemporaries. “Yangrup” refers to Sinam in Taplejung. Sirijanga’s death is confirmed to have occurred in 1834 VS (1777 AD).

In fact, all these were the beginning of great works for the Yakthung civilization. They were Cho?lung achievements.

Revitalizing such great achievements is the Cho?lung Changma ritual. By performing Cho?lung Changma, the Limbu people gain good health, long life, and prosperity.

Descriptions of Scripts and Images:

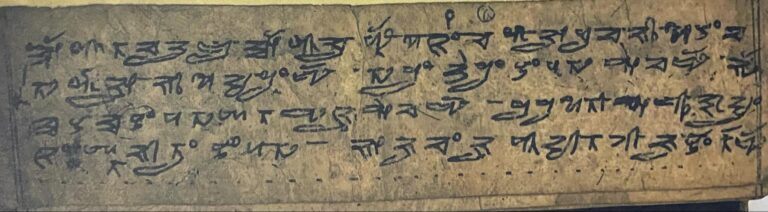

Sirinjunga himself wrote a script stating that he was the descendent of Susuwa Lilim Yakthunghang, which is bound in volume 86, page 1 of the Hodgson Collection.

Sirijanga was born into the Singthebe family of the Yakthung Limbu community in Tellok, Taplejung district. Records about Sirijanga mention that he wrote in his Yakthung language and made Sirijunga script.

According to the book “History of Sikkim,” which was bound in 1908 AD (1965 VS) by the 9th Chogyal (king) of Sikkim, Thutob Namgyal, and Queen Yeshe Dolma, “Sirijanga was born generations later as a descendant of Mujinggna Kheyangna, in Yangrup.”

He trained eight disciples and developed the Yakthung script, standing against the king and Lamas of Sikkim.

The Lamas, using a poisoned arrow, killed Sirijanga by forcing bird feces into his mouth and throwing his body into the river.

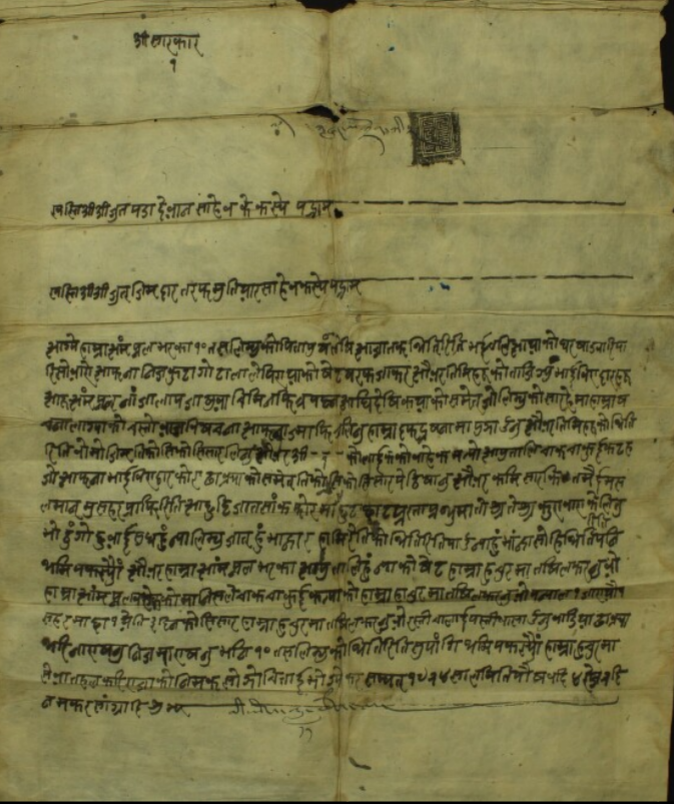

Mukunda Luintel digitized the document syahamohor through a eap.bl.uk on the link, dated 1824 VS, and was issued by Jut Maha Dewan, an authority of the Sen kings in the name of the Limbu people.

At that time, Nepal was ruled by King Singh Pratap, a name referring to Pratap Singh Shah, son of King Prithvi Narayan Shah of Gorkha.

Sirijanga and Pratap Singh Shah seem to be contemporaries. “Yangrup” refers to Sinam in Taplejung. Sirijanga’s death is confirmed to have occurred in 1834 VS (1777 AD).

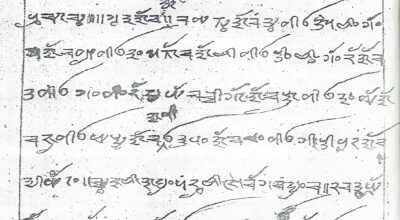

In volume 85, page 44, of Hodgson Collection, the script written in the Yakthung Limbu language and Sirijunga script mentions the “Das Lungbung” and outlines the territorial boundaries of the Yakthung Limbu people.

Brian Houghton Hodgson, a British naturalist and ethnologist who studied India and Nepal, collected this document.

Hodgson first came to Nepal in 1820 AD (1877 VS) as an acting assistant to Edward Gardner, the British Resident.

From 1845 AD (1902 VS), he lived in Darjeeling. Hodgson studied the history, languages, religions, and cultures of various communities, including the Limbu, Rai, Chhetri, and Newar, as well as flora and fauna.

In his research, Hodgson collected notes written in Yakthung Limbu script by Sirijunga from historical sites in present-day Taplejung and Panchthar districts, as well as from Darjeeling and Sikkim.

These collections were gathered through individuals like Jovan Singh Phago, Chyangresing Phedangma, Havildar Randhwaj, and Kharidar Jit Mohan.

These documents were later transported to London via Darjeeling and Kolkata and housed in the British Library, referred to as the “Hodgson Collection.”

Mukunda Luintel digitized the document syahamohor through a eap.bl.uk on the link, dated 1824 VS, and was issued by Jut Maha Dewan, an authority of the Sen kings in the name of the Limbu people.

In this document, there was written the term æDas LimbuÆ. Jovin Kurumbhang, who is currently resident in the United States, provided information about this document.

Comment