When has there ever been good governance in Nepal? Even when I try to recall a time, I can’t find one. It seems that good governance has never truly existed here. It has been a persistent problem—one that we’ve failed to address properly. The bureaucracy bears as much responsibility for this failure as the political leadership.

It is misleading to say that leaders come from elections. Elections give us representatives, not necessarily leaders. Leadership is a distinct quality—one that must be nurtured through experience, vision, and responsibility.

The misconception that winning an election makes someone a leader is deeply flawed. Equally misguided is the belief that one must hold office or win elections to be a leader.

Leadership exists both inside and outside of power. There can be elected leaders, and there can be leaders who’ve never stood for office. Leadership is about personal integrity, vision, loyalty, and capability.

In my view, Nepal’s greatest crisis is a crisis of leadership—and not just in politics. Political leadership may be at the forefront, but we also lack leadership in our homes, institutions, and communities.

Solutions are possible. Good governance is not a myth. But every institution must take ownership of its domain. The Ministry of Health must be held accountable for public health.

We tend to look for leadership in one individual, which is a mistake. Yes, there is only one President and one Prime Minister, but leadership is not confined to those positions. Leadership can be found in the army, the police, the judiciary—it can be found in anyone, anywhere.

We have defined leadership too narrowly. And by placing unrealistic expectations on this limited view, we have only amplified our failures. We needed to seek leadership in governance, in values, in action—not just in politics. Unfortunately, we are modern in appearance but archaic in thought. We enjoy modern conveniences, but our work culture is outdated.

Today, it’s hard to find a single institution in Nepal that embodies good governance. I may not know every institution, but wherever I go, the crisis is evident.

Why don’t young people want to stay in Nepal? Send them to a local ward office, a land revenue office, or any government agency to get a mark sheet—and within three days, they’ll say, “I can’t live here anymore.” We’ve pushed them to that point. We are the reason they no longer believe good governance is possible.

Could I have demonstrated good governance by working in the courts? Could those in the army have done so? Of course, every sector has its mix of good and bad. But can any of us confidently say that there is complete good governance in any one field?

Good governance doesn’t come for free—it is the outcome of a well-functioning system. But what I see is that our regulatory bodies are the weakest links. Every regulatory institution has some flaw. That is why governance has decayed. If the regulators had done their job, the service providers would have been held accountable, and the system would have improved.

We can no longer afford to be careless. This trajectory cannot continue. That is why it is crucial now more than ever to raise our voices, open our ears, and engage in honest dialogue about governance.

The court belongs to all of us. The rule of law is not just a matter of judiciary—it is what I call a “rule of law deficiency syndrome.” Similarly, we suffer from a governance deficiency syndrome and a leadership deficiency syndrome that are deeply embedded in society. These syndromes are the root causes of our underdevelopment.

Our problems go beyond policy—they reflect a moral crisis. We buy laws, buy policies, buy appointments, buy decisions, and sell principles, sell religion, and ultimately sell people. Why can’t we be the one thing that isn’t for sale?

Even our character has eroded. We’ve developed “electronic character”—we know how to talk online—but we’ve failed to cultivate moral character. Our education system has taught us how to fill our stomachs, but not how to nurture our minds or our sense of ethics.

This isn’t just about the curriculum. The civil service exam sends people into government, and while many are competent, the selection process often becomes a competition between the mediocre.

When fools and the uninformed take the exams, the least foolish wins. When they contest elections, one of them wins. But how many truly qualified candidates even run? How many educated, ethical individuals apply?

Why is the country becoming so unattractive to its own people? Why do we feel like we have to leave to live with dignity? Many of us stay only because we lack a visa. This isn’t a trivial problem—it’s a socio-psychological crisis. And at its core lies the absence of good governance.

Good governance should be a subject of discussion at every level of our society. People must be informed—again and again—about its importance. But we have failed to point fingers where necessary.

Instead, we saw value in obedience and risk in asking questions. So we continued to operate within a framework of passive compliance—an obedient democracy. I call it a democracy where the leader won, but the people lost.

From the ground level, citizens say they fulfilled their duty—they voted. But after that, where do they encounter the leaders they elected? For the next five years, where is the space for meaningful engagement between the people and their representatives?

The elected leaders return to their own party circles, but what about citizens who belong to other parties—or to none at all? Where can they go to voice their concerns? The current system of representation has created a dangerous distance. And this isn’t limited to politics—it’s a model replicated in every sector.

People say, “Don’t spread despair; at least give us hope.” But should we spread false hope built on lies? No—truth must come first. That is why we must create spaces for questioning. Let’s form a collective of questioners, a chain of accountability. We have reached a critical point. If we’ve reached a breaking point, shouldn’t we pull the thread and expose what’s underneath?

Speaking of the judiciary, I’ve said this since my time as Chief Justice: if you design a constitution that is inherently political, how can you blame the judiciary for acting politically? The same court is expected to make appointments and also deliver impartial judgments?

There’s an elaborate appointment mechanism, yet no one in that system takes responsibility. The drafters of the constitution don’t take responsibility. Those who make the decisions are burdened with accountability, while those who lose or win those decisions play the blame game.

Where is the real commitment to systemic reform? Who has stepped up to fix the structural weaknesses? We must examine all these problems holistically—not in isolation.

We must be ready to lose something in order to gain a future. It’s time to empower citizens to take risks, to speak up, to ask hard questions. It is time to educate the public—not just with information, but with courage and critical thinking.

Solutions are possible. Good governance is not a myth. But every institution must take ownership of its domain. The Ministry of Health must be held accountable for public health.

The Ministry of Finance must answer for economic decisions. Who sets the standard in each institution? Who is the ideal secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs? Who is the role model in Health, in Finance?

Every institution should have models of excellence—figures we can proudly point to and say, “That leader made a difference during their tenure.” Why haven’t we produced such individuals?

The truth is, there is profit in dismantling good governance, and loss in trying to uphold it. Jobs are threatened. Comfort is disturbed. But regardless of the risk, this is the time to act.

We must be ready to lose something in order to gain a future. It’s time to empower citizens to take risks, to speak up, to ask hard questions. It is time to educate the public—not just with information, but with courage and critical thinking.

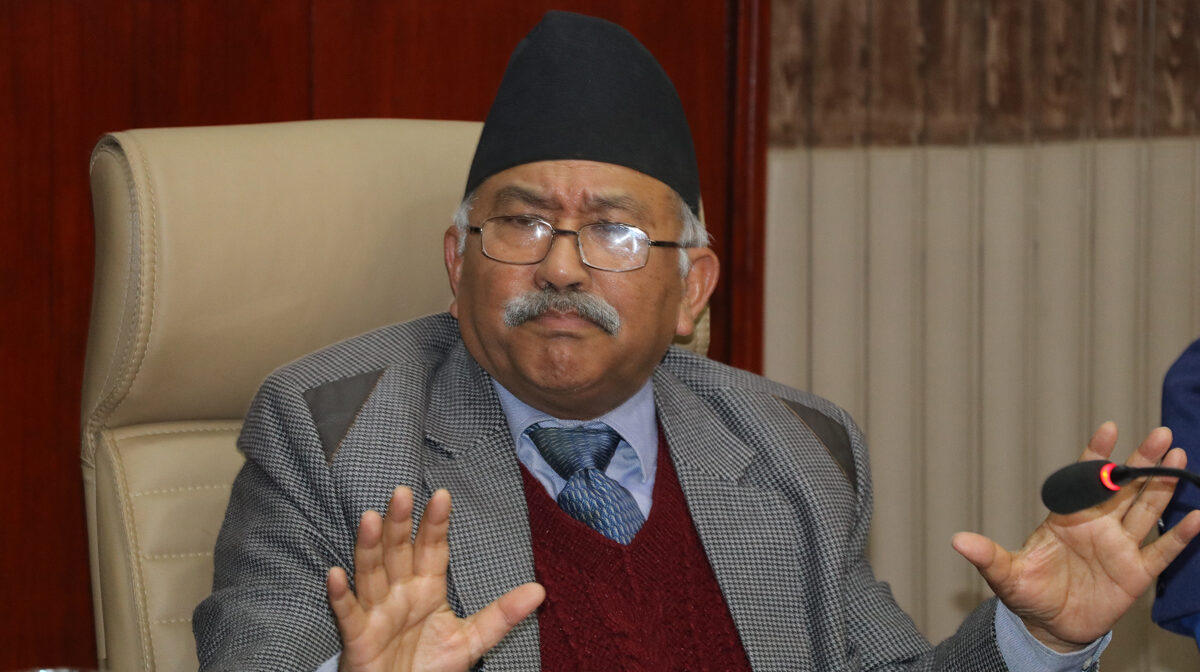

(Edited excerpt of remarks by former Chief Justice Kalyan Shrestha at a discussion organized by the Institute for Strategic and Socio-Economic Research (ISSR) on good governance)

Comment