Introduction to Yakthung/Limbu/Limbuwan: Yakthung Limbus are densely populated between the Arun and Tamor rivers in the far east of Nepal.

The civilization of the Yakthung Limbu grew in the vicinity of the Kumbhakarna/Phaktanglung, Kanchanjangha/Kelangsitlang, Tokpegola/Singshaden mountains, and it flows along with the rivers: Tamor Khola/embiri yangthangwa, Ghunsa Khola/mudhingum lekwawama, Miwa Khola/kettakum miKwa, Maiwa Khola/Sindholung Maiwa, Fawa Khola/Yafa/Lung Fawa, Kabeli Khola/muganglung kangwa, Tawa, Ingwa, Sabhawa, Hengwa, Piluwa, etc.

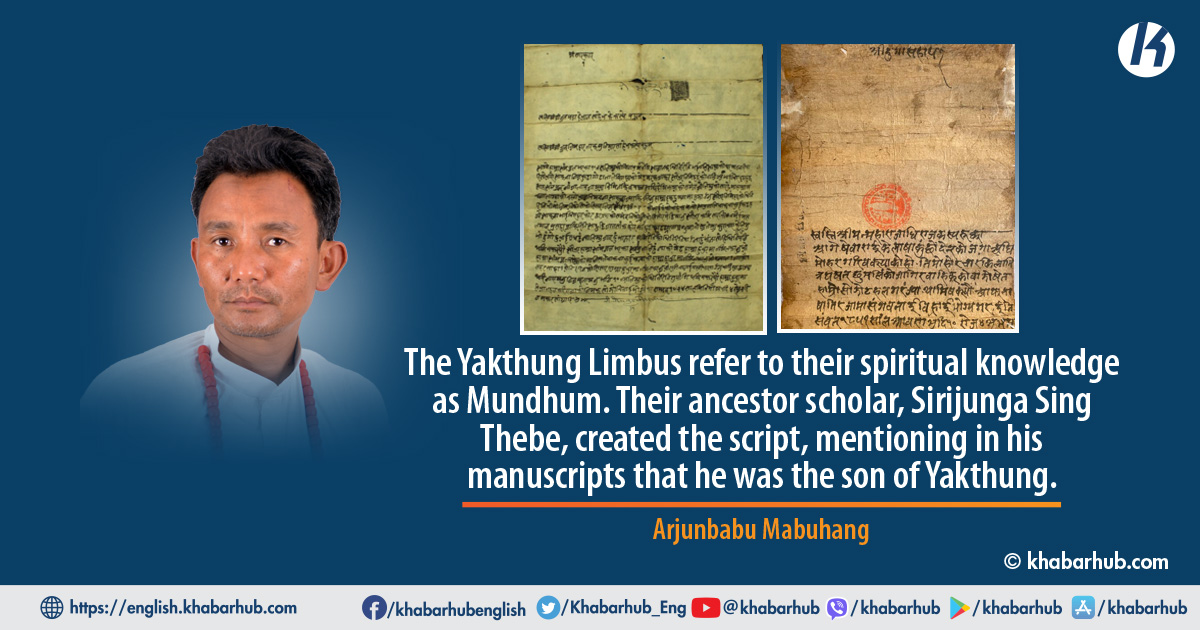

The Yakthung Limbus refer to their spiritual knowledge as Mundhum. Their ancestor scholar, Sirijunga Sing Thebe, created the script, mentioning in his manuscripts that he was the son of Yakthung.

“Yakthung” translates to “son of earth.” The Yakthung Limbus developed their own traditional laws in social development, practicing the customary law called samyoklung/dubo dhungo.

To seek justice, Yakthung Limbus gathered in chumlung assemblies, and a group of noblemen called tumyang resolved issues.

Culprits were punished by touching dubo/cynadon dyctlon, and afterward, a dhungo pillar of stones was buried as evidence.

At that time, such stone pillars represented the kingdom and ruler, known as lungbung.

After contact with the Sen king, they were called Limbu. The word “Limbu” might have originated when the Sen ruler pronounced “lungbung.”

Initially, ten Yakthungs built these lungbungs, and those who buried ten lungbungs were called “daslimbu.”

Consequently, the land of Yakthung Limbus was referred to as Limbuwan by the Gorkhas.

The Gorkha soldiers faced challenges in effectively collecting taxes. Consequently, the Limbu elite, known as tumyang, was bestowed the titles of subba, subhangi, and raya, along with the responsibility to collect taxes and administer justice.

Until the Sen and Shah periods, the lands of daslimbu had divisions into ten administrative positions based on place names and Yakthung Limbus clans, such as fago, sireng, fedap, sudap, pradhap, yangrup, mikluk, bodhe, papo, le?wa, abo, thindolung, chemjong, etc.

These kingdoms were associated with the Sen kings of Vijaypur and the Namgyals of Sikkim.

King Prithvi Narayan Shah’s unification of Nepal severed the relationship between Sikkim and the Yakthung Limbus.

During the Rana period, the traditional administrative division of ten Limbus increased to seventeen divisions or satrathum. Hence, the phrase “daslimbu satra thum” was once popular.

Until the Land Reform Legislation of 1964 AD, Taplejung, Terhathum, Sangkhuwasabha, Panchthar, Ilam, and Dhankuta districts were divided into a total of 23 division thum.

The names of the thums included sankhuwa uttar, sabha uttar, panch khappan, panch majhiya, das majhiya, maiwa khola, miwakhola, tamorkhola, athrai, phedap, yangrup, panchthar nubho uttar, panchthar nubho dachhin, ilam, maipar, puwapar, fakfok, choubis, mikluk, jhalhara, khalsa, chhathar, dhankuta, etc.

The Kipat tenure system of the Gorkhali ruler: During the unification campaign, Gorkhali King Prithvi Narayan Shah crossed the Arun river in the east.

On the banks of the Arun River and Sabhawa Khola, a significant battle occurred between Gorkhali soldiers and Yakthung local chiefs.

The king was compelled to make a treaty without a clear victory or defeat.

According to the treaty, King Prithvi Narayan Shah confirmed all the customs, traditions, rights, and privileges of the Yakthung Limbus enjoyed under the Sen king.

In 1774 AD, King Prithvi Narayan Shah granted a red seal to the Yakthung Limbus. Scholar Mahesh C. Regmi translated this red seal on page 540 of his book “Land Tenure and Taxation in Nepal,” published in 1963-78 AD. The translated red seal’s main part is as follows:

“Although we have conquered your country by the dint of our valor, we have afforded you and your kinsmen. We hereby pardon all of your crimes and confirm all the customs and traditions, rights, and privileges of your country. Enjoy the land from generation to generation, as long as it remains in existence. In case we confiscate your lands, may our ancestral gods destroy our kingdom.”

All the wastelands and forests were owned by the Limbus from time immemorial, referred to as “haktak.”

Limbus are pioneer cultivators of Limbuwan. King Rana Bahadur Shah, the grandson of King Prithvi Narayan Shah, implemented the Kipat tenure system.

The Gorkhali policy of collecting tax on the barren land of Limbus was called the Kipat tenure system.

Tax collection in Limbuwan began in 1786 AD, with Gorkhali soldiers of Srijung and Srinath Compu Paltan Brigade collecting taxes. Initially, the tax had to be paid in Vijaypur and later sent to Chayenpur.

From 1895 AD, thums/divisions within the present Sankhuwasabha, Terhathum, Taplejung, and Panchthar districts collected revenue at Myanglung of Terhathum mal [revenue-collected unit].

Terathum district got its name from this.

Since 1780 AD, Dhankuta Gouda [regional administrative center] and since 1818 AD, Ilam Gouda was established.

Only after some time did six thums in Dhankuta (currently parts of Terhathum and Dhankuta districts) and four thums in Ilam (currently all parts of the Ilam district) begin tax collection.

Despite decrees encouraging the Limbus to “be satisfied, cultivate the land, and settle,” and “enjoy your ancestral land from generation to generation,” Kipat landholders enjoyed income tax only until the upcoming revenue settlement.

The Gorkha soldiers faced challenges in effectively collecting taxes. Consequently, the Limbu elite, known as tumyang, was bestowed the titles of subba, subhangi, and raya, along with the responsibility to collect taxes and administer justice.

To attain the rank of subba, a Limbu needed to pay an initial fee of Rs 26.00 and surrender 30 muris of land.

The judicial committee, consisting of subba, karbari, budheuli, and mukhiya/thari, worked collectively, known as amal.

The amal of Subba handled all cases, excluding panchakhat; hatya [murder], gau hatya [cow slaughter], bramha hatya [murder of Bramhan], stri hatya [murder of a woman], bal hatya [murder of a child].

Subba presided over judicial functions like danda kunda garnu/thingro mungro thoknu [settling disputes and fighting], jar hannu/chak [dealing with disputes arising from domestic issues], chakui khojnu [finding a husband for a widow].

Additionally, Subba was responsible for carrying mail hulak toda from his amal/jurisdiction area to another Subba’s amal, delivering military arms and treasure kampanika besouti. Subba also oversaw the maintenance of the small village market.

Various commodities such as giant honeybee bhir mahuri ko maha, Indian bison/gouri gai ko sing, ivory/hatti dant, rhinoceros tusk/gaindako khag, a bird catcher buzzard/asmani bajabi as bankar [forest levy], balitora/tite machha, as jalkar [a tax on the stream], and gad dhan [tax on gold, iron, and copper mining, etc.] had to be brought to the king.

Since 1790 AD, Shah rulers issued orders in Limbuwan to collect taxes on titles like Saune Phagu, bhedabhara [levy paid by selling cattle in the months of July and February], Serma [paying levy in farmland]. Initially, as Limbu was the predominant population in Limbuwan, levies were collected based on households in kipat land.

Furthermore, Subba handled customary laws of Yakthung Limbu, such as samyoklung [already discussed], lung phomma/tharo halnu [demarcating land boundaries by hanging stones], najong-khemjong [rite to leave husband], metlung phusingma [to receive mourning rites from in-law’s house], shasing lapma [adopting a child], ka?ai sodhok semma [to settle incestuous relationships].

Over time, the settlement of non-Limbu increased. Limbu kipat landholders used to take chardam ¼ = 1 ana from rait/dhakre [taxpayer] and allow them to cultivate the land within the kipat boundary.

Despite decrees encouraging the Limbus to “be satisfied, cultivate the land, and settle,” and “enjoy your ancestral land from generation to generation,” Kipat landholders enjoyed income tax only until the upcoming revenue settlement.

After Limbus’ complaints, since 1834, revenue settlement has been adjusted on a decennial basis.

During the interval between two revenue settlements, only one dam was not remissioned to Subba, and the government did not demand any increment.

On the day of land measurement, Subba had to issue a bill chalanipurji in the name of Dhakre/layman/Rait taxpayer, a system known as sorhaani.

The land would then be converted into raikar, and this conversion of Kipat land into raikar [alienation] land is referred to as Thekkathiti [land allotment system] in Limbuwan.

In Raikar land, taxes were collected based on land measurement. Depending on occupation, the blacksmith paid as tale, cobbler as mekchan, Newar as chhipo, tailor as sujero, and jogi as phakir, etc.

Similarly, tax levied on digging a spade was called kodale, and a plow hale tax was charged for keeping a bollock.

The tax levied on those who reared only one bull was called pate.

Twice a year, Subba received two laborers as bethbagar free from each rait/dhakre or taxpayer in tilling and harvesting seasons.

Similarly, Subba collected tax as kharcheri from sephard/cowherd gothala for cattle grazing.

Violation of the agreement by the Gorkhali ruler: Although the Gorkhalis made an agreement to confirm the culture and privileges of the Yakthung Limbus, they could not follow through.

In this, Subba received meat from animals and birds as sisahar from hunters for hunting in the forest.

Furthermore, Subba handled customary laws of Yakthung Limbu, such as samyoklung [already discussed], lung phomma/tharo halnu [demarcating land boundaries by hanging stones], najong-khemjong [rite to leave husband], metlung phusingma [to receive mourning rites from in-law’s house], shasing lapma [adopting a child], ka?ai sodhok semma [to settle incestuous relationships].

Subba was required to deliver the tax to the office of the tax collection gauda by the end of March.

If he failed to pay, his coparcener/successor (his eldest son or brother) was given seven days to pay the remaining dues.

If Subba’s successor paid the remaining arrears, he would be appointed Subba. If the successors of Subba also failed to pay the remaining dues, then non-Limbus were asked to exercise the rights of Subba.

If the remaining arrears could not be recovered even from the non-Limbus, Subba’s kipat land would be converted into raikar [taxable land].

The government aimed to clear the forest and build settlements on barren lands to increase taxes quickly.

Since 1899 AD, the government initiated the usufruct system in Kipat land. Limbu pledged Kipat for a loan with a borrower.

When additional expenses were needed, the mortgage was transferred to another borrower with an increase, a practice called bhogbandhaki/badh khane.

The system of badh did not charge interest on the loan, but the loan increased day by day.

Limbu even took loans for masikatta, where the principal amount was reduced from the income of the mortgaged land. Limbu couldn’t redeem their Kipat land.

Though the Gorkhalis addressed the Yakthung Limbus as ‘the king of the non-enslaved caste,’ according to Hindu religious law, Yakthung Limbus were placed in the enslavement caste.

Finally, in 1964, the government abolished the Kipat system and enacted the Land Reform Legislation [hereafter LRL] Act.

Violation of the agreement by the Gorkhali ruler: Although the Gorkhalis made an agreement to confirm the culture and privileges of the Yakthung Limbus, they could not follow through.

The term “Kipat” did not originate from the Yakthung Limbu. In 1750 AD, Karna Shahi, a descendant of Raskoti Malayvarma of Dailekh, was found to have started the kipat tenure system.

The Yakthung Limbu referred to the land owned by them as haktak, but the Gorkhali referred to the land won by the Yakthung Limbu as kipat.

Similarly, administrative words like subba, raya, and amal did not come from Limbu terminology; they were influenced by the Mughal, Sen, and Shahi kingdoms.

These administrative words led to the abolition of collective institutions like Lungbung, Tumyang, and Chumlung of the Yakthung Limbus.

Yakthung Limbu was ruled by Dubo dhungo/Samyok Lung through Tumyang.

In the Sen and Shah periods, Yakthung Limbu began to be ruled by Nagara Nishan (the instrument like drum and spear used by the Sen and Shah rulers as a symbol of victory in war) and through Bramhan Pandit [erudite].

Limbu’s faith began to change due to someone’s strength and arrogance. Even when the upper castes were to be cleansed from the lower castes, taxes were levied, a practice known as Chandrayana.

The Yakthung Limbus, who believed in their traditional customs, were forced to pay such taxes.

Outwardly, the Kipat system appeared as the milk of a kamdhenu cow for the Yakthung Limbus, but internally, white milk was mixed with white poison, leading to the end of ancestral land and traditional rights.

Additionally, Yakthung Limbus were required to pay Mekchan tax for slaughtering cattle (especially cows and bulls) using leather, even though the skins were used to make magazines for weapons.

This tax was called Mekchan. Despite the ban on slaughtering cows, the Yakthung Limbus had to do so to appease the deity.

Though the Gorkhalis addressed the Yakthung Limbus as ‘the king of the non-enslaved caste,’ according to Hindu religious law, Yakthung Limbus were placed in the enslavement caste.

Recognizing the bravery of the Yakthung Limbus in the battles of Bhot and Lucknow, Janga Bahadur Rana declared them non-enslaved.

The government also encroached on the hereditary rights of Subba over the Kipat land.

If Subba could not pay the tax on time, non-Limbus were allowed to pay the tax and run the jurisdiction.

Similarly, for tax collection and judicial service of Chhetri-Bramhin caste, the government managed Thari only from Chhetri-Bramhin caste.

The LRL Act of 1964 gave importance only to the loans taken by the Limbus. The value of their land was not increased, making this Act biased in favor of Bramhin-Chhetri.

Layman/Dhakre/Raite or taxpayer could not occupy all the lands that Limbu assigned the boundary of Kipat charkilla.

Dhakre/raite or taxpayer cultivated only the cultivable land within the boundary, and the rest of the land should be kept in the Limbu’s Kipat.

However, the government forcibly declared such plots as forest Rani Ban areas.

Outwardly, the Kipat system appeared as the milk of a kamdhenu cow for the Yakthung Limbus, but internally, white milk was mixed with white poison, leading to the end of ancestral land and traditional rights.

Comment