KATHMANDU: 75-year-old Jasbir Bishwa from the Bhutanese refugee camp in Beldangi, Jhapa is bedridden due to high blood pressure and kidney problems. Despite having a family of five, he struggles to afford regular check-ups.

“There is no source of income, and I’m unable to work,” Jasbir laments. “You can’t even get sick or eat properly; it feels like a life of hell.”

Jasbir’s plight worsened when he was unable to resettle in a third country due to his son’s mental health issues.

“That’s when my difficult days began. The relief we used to receive has stopped, and the diseases have consumed my body, forcing us to endure extreme pain,” he adds.

The grim reality for Bhutanese refugees in Nepal is partly attributed to human rights leader Teknath Rizal, whose actions led to a loss of credibility for the refugee community.

After reports surfaced that some individuals were improperly receiving funds for resettlement, donor support dwindled, compounding the refugees’ struggles, particularly as the Nepalese government remains indifferent.

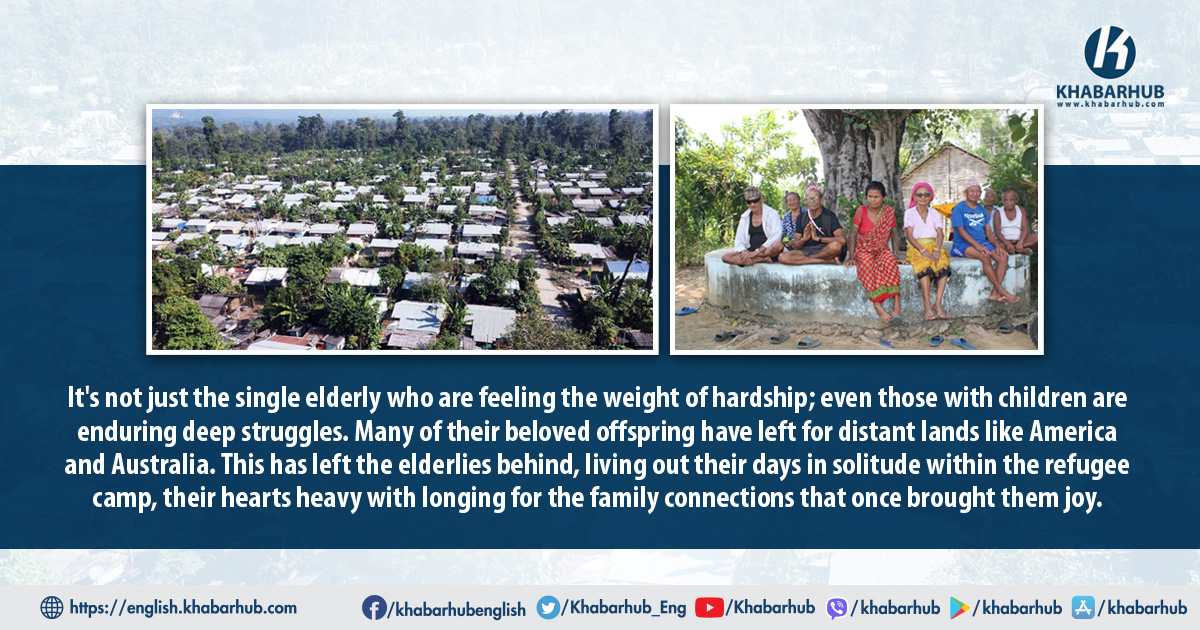

Recently, it’s not just the single elderly who face hardships; even those with children struggle. Many of their offspring have resettled in America, Australia, and other countries, leaving senior citizens to live solitary lives in the camp.

Asha Rai, co-secretary of the Bhutanese Refugee Camp in Beldangi, expresses her dismay over the tarnished reputation of refugees in the international community.

“The fake Bhutanese refugee case has severely affected us. With donors pulling back their support and resettlement programs on hold, we are living in pain. Our future lies in the hands of the Nepalese government, and we struggle to make ends meet,” she says.

“They need to address our repatriation, rehabilitation, and integration. Discussions with the Bhutanese government regarding repatriation are essential.”

Asha emphasizes that genuine Bhutanese refugees are suffering due to the fallout from fraudulent cases.

The complications of renewing identity cards add to their challenges. According to Champa Singh Rai, Camp Manager of Pathri Sanischare, there are 6,365 Bhutanese refugees in the Beldangi and Pathri Sanischare camps in Morang and Jhapa districts.

Since 2016, the resettlement process has come to a complete halt. Approximately 2,000 refugees are at risk of missing registration for various reasons, leaving their futures uncertain.

Dreams of returning to their homeland, Bhutan, feel distant, and the path to resettlement remains closed, forcing many to navigate a bleak existence.

Elderlies suffer the most

Ishwari Neupane, a 91-year-old resident of the Beldangi camp, finds herself alone in her final days, desperately needing support.

Her story reflects the broader struggles faced by the elderly in these camps, highlighting the urgent need for assistance and intervention.

“After my brother-in-law passed away in Bhutan, I raised my two nieces as daughters. Since they went to America after being rehabilitated, I have been alone here,” she said.

“After my daughters left, I stayed in the Maidhar Temple for five years. I returned to the camp a year ago because I couldn’t cook in the temple.” She now lives with her nephew Chabinath.

Sixty-six-year-old Krishna Bahadur Majhi, a Bhutanese refugee in Beldangi, Damak, faces loneliness in his old age.

Despite suffering from various health issues, he has no one to cook and care for him. Hard of hearing, he relies on what he can ask for and what his helpers provide.

The struggles of eighty-four-year-old Min Prasad Gurung and seventy-five-year-old Kabimaya in the Pathri Sanischare camp are similar.

Although their three daughters are married, the Gurung couple lives alone at a time when they need support. Neighbors help care for them during illness.

Eighty-year-old Jit Bahadur Rai also finds himself alone. His five children and grandchildren have been in America for five years, while his youngest daughter married and moved to Darjeeling, India.

When the resettlement plan was proposed, he held onto hope of returning to his homeland, only to face loneliness in his final days.

“I can neither return to my country nor live with my children. They used to say, “Twelve sons and thirteen grandsons rest on the shoulders of the old man.” As a father of six and grandfather of 10, I feel isolated,” he lamented.

“Due to the inaction of the Nepalese government, conditions in the camp are worsening. Family disintegration is leading to increased mental health issues,” says Rizal.

Recently, it’s not just the single elderly who face hardships; even those with children struggle. Many of their offspring have resettled in America, Australia, and other countries, leaving senior citizens to live solitary lives in the camp.

These shared sorrows reflect the plight of elderly refugees forced from their homeland.

For years, many in the camp have been deprived of the warmth of familial love. Many homes lack fire in their stoves, and even basic care, like water during illness, is often absent.

Dawa Tamang, the administrator of the Pathri Sanischare camp, states, “Senior citizens, along with the sick and disabled, are facing significant challenges due to age-related issues. Their struggles with food, living conditions, and both physical and mental health are deeply intertwined.”

The camp management committee lacks an exact count of senior citizens residing there.

However, according to UNHCR, there are currently 749 elderly individuals over the age of 60 in the Sanischare camp and Beldangi camp in Jhapa.

Out of these, 602 are in Beldangi and 137 in Pathari Sanischare. This number may decrease as time goes on, based on data collected by UNHCR up to 2019.

According to UNHCR, there are 5,039 Bhutanese refugees in Beldangi camp in Damak, Jhapa, and 1,491 in Shanishare camp.

In total, there are 6,577 refugees, including 19 who live outside the camp, all currently under arrest.

Among the refugee solution options—repatriation, resettlement, and localization—third-country resettlement was preferred, but this process has been completely closed since 2016.

At present, neither repatriation nor localization options have progressed, and the resettlement process remains stalled.

According to Govinda Rizal, Program Manager of the Bhutanese Refugee Disabled Association in Beldangi, the donor agency has stopped providing rations for living since 2018.

Following the closure of the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Damak in 2020, Bhutanese refugees find themselves in a state of confusion.

Additionally, 206 refugee women married Indian men, and 197 refugee men married Indian women, resulting in 872 children from mixed marriages and 572 children of Indian Bhutanese.

“Due to the inaction of the Nepalese government, conditions in the camp are worsening. Family disintegration is leading to increased mental health issues,” says Rizal.

“Some family members are in third countries while others remain in the camp, and the chances of reunion are diminishing. As a result, drug use is on the rise.”

He adds, “Now, options for resettlement should be opened for refugees, including repatriation, integration, and family reunification. We are waiting for the government’s decision.”

Doors to homeland (Bhutan) are closed, and hope for rehabilitation is meager

The UNHCR, the donor agency based in Damak that used to support refugees, has already left.

For the past two years, it has ceased providing rations and other essential services. Health and education facilities in the camp have nearly disappeared.

Bhutanese refugee children must travel long distances to attend public schools, as the camp previously housed its own schools and primary health care.

Most people in the camp now struggle to meet their basic needs for food, education, and health care for their children. With the UNHCR office closed, many doubt that the door to return home will ever reopen.

“I once said I didn’t want to go to America; I loved my country. But now, I am alone,” says Jit Bahadur.

“I cannot return to the land where I was born, nor can I go to the country where my children have gone. We are left here in despair.”

Until 34 years ago, they were sovereign citizens of Bhutan, proud of their homeland. They would say, “This is my country,” but that pride crumbled.

Their own country became a stranger, and they were forced to flee. They began living as refugees, hoping one day to touch their homeland’s soil again, residing in various camps in Jhapa and Morang.

Many attempts to return home failed, leading to the initiation of a resettlement process as a solution to their plight.

Approximately 150,000 refugees have been resettled in third countries. Initially, 90 percent of Bhutanese in seven camps relocated to eight different countries under the resettlement program.

After this, many refugees from the Damak-Beldangi and Pathri-Sanischare camps expressed a strong desire to return to Bhutan.

“More than 5,000 people intend to return to Bhutan,” said Tek Bahadur Rai, secretary of the Beldangi camp management committee.

According to him, there are 1,694 registered shops in Beldangi. Among the residents, 2,012 hold identity cards, while 188 refugees are unregistered, 400 are not registered for various reasons, and 300 Bhutanese lack any registration.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Nepal reports that a total of 113,500 refugees with Bhutanese identity have been resettled in eight countries, including the US, UK, Norway, Netherlands, New Zealand, Denmark, Canada, and Australia.

Children born in the camps since 2022 are not included in these statistics; only 338 newborns are reported.

Prior to 2019, there were 971 cases of mixed marriages among refugees: 222 refugee women married Nepali men, while 346 refugee men married Nepali women.

Additionally, 206 refugee women married Indian men, and 197 refugee men married Indian women, resulting in 872 children from mixed marriages and 572 children of Indian Bhutanese.

Background of Bhutanese refugees

Nepali-speaking Bhutanese fled to eastern Nepal after being expelled by Bhutanese rulers in 1991.

Seeking safety as refugees, they initially settled in tents along the banks of the Kankai river.

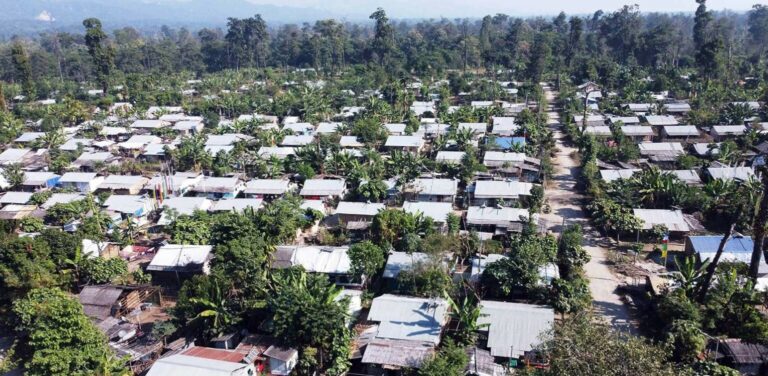

In 1992, the UNHCR began monitoring their situation. Seven camps were established to house Bhutanese refugees, including three camps in Beldangi (Damak) and others in Khudunabari, Timai, Goldhap, and Pathri Sanischare in Morang.

Following resettlement efforts, the number of camps has since been reduced to two: one in Beldangi in Damak and one in Sanishchare in Pathri.

Due to Bhutan’s reluctance, there has been no dialogue on refugee issues since 2003.

However, beginning in 2007, Bhutanese refugees have been resettled in third countries thanks to the efforts of the international community.

Despite this, a number of refugees have built concrete homes. Currently, only one-third of the refugees remain in the Pathri Sanischare camp, which spans a total of 48 hectares of forest land.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Nepal reports that a total of 113,500 refugees with Bhutanese identity have been resettled in eight countries, including the US, UK, Norway, Netherlands, New Zealand, Denmark, Canada, and Australia.

Bhutan maintains that its citizens, who were forcibly deported in the 1990s, are not refugees.

In a report submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2014, Bhutan referred to these individuals as illegal immigrants.

The last round of talks on refugee return took place in 2006, after which Bhutan has consistently refused to engage in further discussions.

Agricultural activities among refugees

Most refugees in the Pathri Sanishchare and Beldangi camps are involved in agricultural activities.

Some have even begun constructing concrete structures within the camp, which is generally prohibited.

Despite this, a number of refugees have built concrete homes. Currently, only one-third of the refugees remain in the Pathri Sanischare camp, which spans a total of 48 hectares of forest land.

There are more than 24,000 refugees in total, with most having relocated under the third country resettlement program; only about 1,400 refugees currently reside in the camp.

With many refugees having left, significant areas of the Pathri Sanischare camp now lie vacant, and some refugees have taken to farming these lands. Dawa Tamang, the camp administrator, noted that they are also raising livestock.

According to Tamang, approximately one bigha of land inside the camp has been encroached upon.

Local residents have constructed a religious temple in addition to engaging in farming activities. Recently, refugees have started raising animals and cultivating vegetables in the vacant areas.

Although encroachment on forest land is occurring, the forest office is currently under-resourced.

Utsav Thapa, Divisional Forest Officer of the Morang Divisional Forest Office, stated that he was unaware of any encroachment within the camp but will investigate the situation further.

“It is not permissible to farm on forest land without authorization,” Thapa explained. “If it is determined that the forest land is being used for agriculture, we will take appropriate action.”

Thapa mentioned that he has just been transferred to Morang and is in the process of familiarizing himself with the situation. He assured that a study will be conducted on the condition of the forest land.

Comment