KATHMANDU: In the quest for a savior, a faction of Nepali society pins its hopes on Durga Prasai, presenting him as a “formidable hero” poised to revive the monarchy.

The belief is that Prasai holds the key to solving the nation’s woes by ushering in the return of the monarchy.

His claim that the mere reinstatement of the monarchy will automatically lead to the forgiveness of bank loans adds a unique twist to his narrative, intertwining financial concerns with the monarchy’s resurgence.

But can Prasai truly emerge as the hero that Kamal Thapa and Rajendra Lingden could not?

The dynamics of leadership are intricately linked to societal aspirations, and in this scenario, Prasai appears to have been born from the collective consciousness yearning for a transformative figure.

The trajectory of leadership in Nepal has witnessed various shifts.

The disillusionment with the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML led to the rallying cry for Gyanendra Shah in 2058/059, only to embrace republicanism within a year.

The subsequent electoral victories of the Maoists and later the rise of KP Oli failed to provide lasting solutions, leading voters to seek alternatives.

Rabi Lamichhane briefly captured public imagination in the 2079 elections, signaling a growing dissatisfaction with traditional political figures.

Now, Prasai has emerged as a figure commanding attention in the pursuit of a “new hero”.

Rajendra Lingden’s shift towards royalism further complicates the political landscape, as Prasai navigates without a clear party affiliation or defined political direction.

The burning question remains: Will Durga Prasai spearhead the movement to resurrect the monarchy and guide the chariot to Narayanhiti?

Is he the main charioteer, or will the likes of Rajendra Lingden and Kamal Thapa share the reins? The complexity of these questions underscores the intricacies of the royalist movement.

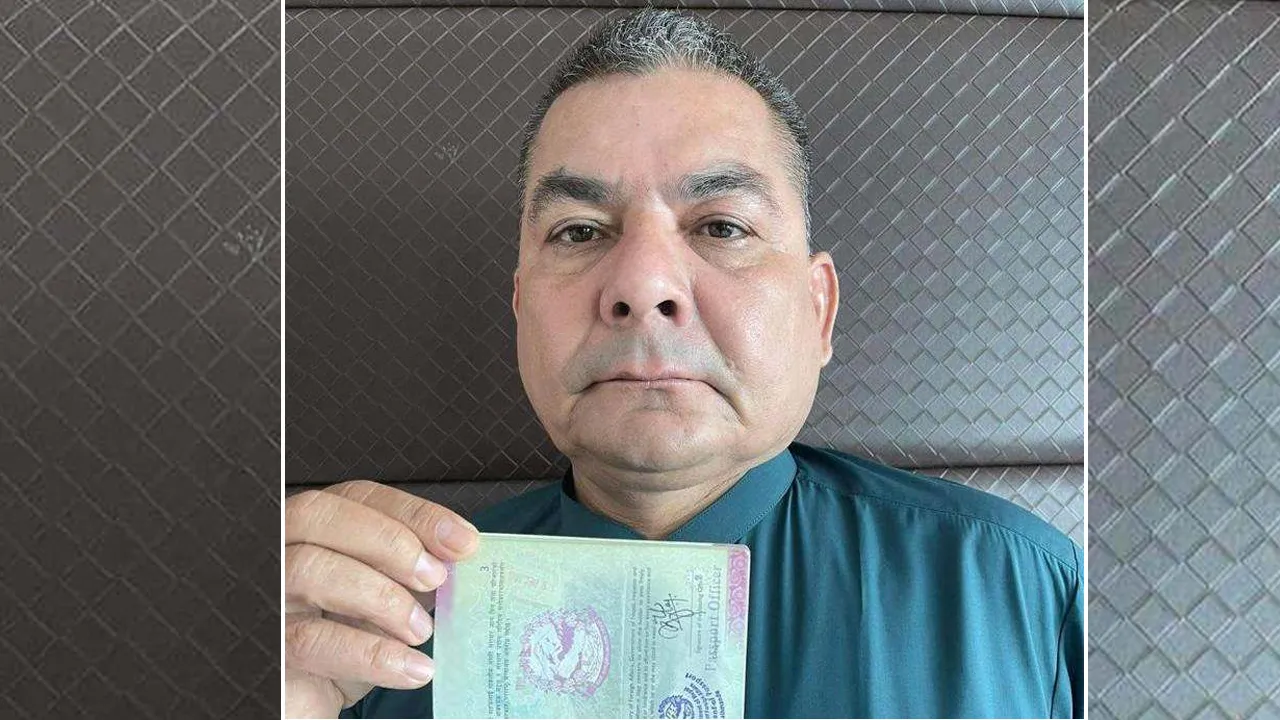

Durga Prasai’s controversial past adds another layer to the unfolding narrative.

As he champions the cause of the monarchy, the duration of his allegiance to the former king remains uncertain.

In a recent press conference held at his Bhaktapur residence, Prasai, deflecting inquiries about the king, emphasizes the pressing need to address the bank loan crisis.

As the spotlight intensifies on Durga Prasai and his enigmatic role in the royalist movement, the future of Nepal’s political landscape hangs in the balance, awaiting the resolution of these complex questions.

Prasai’s controversial persona

Durga Prasai’s public appearances are marked by provocative and at times violent speeches, with claims that making Gyanendra or Paras ceremonial kings would miraculously solve the country’s problems.

However, his leadership style raises concerns as he fails to embody the decorum expected of a leader.

A leader, especially one aspiring to lead a nation, should exhibit respect for diverse opinions, a quality seemingly absent in Prasai’s confrontational approach towards critics.

Prasai’s speeches often take a combative tone, suggesting a willingness to resort to physical measures against opposition.

The prospect of such a figure wielding power raises questions about the potential repercussions for dissenters and critics.

What would be the fate of dissenters if Prasai assumes a position of authority? It’s a question that looms large, adding complexity to the discussions surrounding his political ambitions.

One distinctive feature of Prasai’s oratory is his repetitive use of a specific phrase in “Thet Jhapali Para” (typical Jhapali style).Beyond his confrontational rhetoric, Prasai consistently highlights his perceived bravery and wealth in his speeches, contributing to an image that raises eyebrows among both supporters and critics.

Now, let’s delve into the background of Durga Prasai and how he rose to prominence.

Born in Atharai, Tehrathum, and later migrating to Jhapa, Durga Prasad Prasai entered the world during the Jhapa movement, with his citizenship indicating a birthdate of Baisakh 20, 2028.

Presently residing near Arjundhara Municipality’s bus park, Prasai hails from an agricultural background, unable to pursue education beyond the eighth grade.

His family’s former farm near the current B&C Hospital was the stage for his early life.

A familial dispute arose over property, leading Prasai to embark on a “justice fight” against his in-laws.

Seeking the assistance of Maoist fighters, he attempted to settle the matter through what he termed as “punishment.”

Before joining the Maoists, Prasai contemplated seeking employment abroad, initiating the process and eventually fleeing to Europe.

Upon returning after a year, he ventured into buffalo breeding in Jhapa, drawing upon skills supposedly acquired during agricultural work in Poland.

Notably, Prasai’s buffalo rearing business thrived, earning commissions and recognition in Jhapa.

Described as adventurous and a risk-taker, he engaged in unconventional practices, such as importing buffaloes from Haryana, India, and navigating the challenges of his enterprise.

Prasai’s business acumen continued to flourish, transitioning from selling milk on a motorcycle to using a car and expanding to cross-border trade, including trips to Mechi bridge and India.

His charismatic speaking skills played a pivotal role in the success of his ventures.

During the Maoist insurgency, Prasai’s support extended to transporting Maoist fighters in his milk-laden vehicle, providing assistance during the underground period.

However, his involvement led to his arrest by the army, though he was eventually released due to his past association with the Nepali Congress.

Prasai’s resilience during periods of political upheaval underscores his complex journey, marked by controversy, business ventures, and an unconventional blend of activism and entrepreneurship.

Prasai’s journey: Economic rise, political shifts, and controversial actions

Amid familial disputes, the Maoists’ intervention took a tragic turn for Durga Prasai, as they abducted his brother-in-law, leading to his demise.

The coercion prompted Prasai’s mother-in-law and wife to finally receive a share, with locals suggesting that the subsequent sale of the land catapulted Prasai into sudden billionaire status, attributing his economic ascent to the Maoists.

Even after the Maoist peace process, Prasai’s fortunes continued to fluctuate.

He resided with the Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda family in good standing, but his rapport soured as leaders in Jhapa, including Dharamshila Chapagai, began opposing him, claiming it was the era of the affluent.

The 2070 BS election weakened the Maoists, and Prasai, eyeing opportunities, aligned himself with the UML, asserting a familial connection with KP Oli.

However, internal strife emerged within the UML, as Prasai sought to contest from Jhapa constituency number 3, a desire thwarted by Oli in favor of RPP Chairman Rajendra Lingden.

Oli’s disinterest in a proposed medical college further fueled discontent, leading to calls within the UML for punitive measures against Prasai.

The Koshi State Committee formally recommended action against him, triggering Prasai’s shift to royalism.

Prasai, known for his vocal stance against banks, manifested his discontent by bringing two dozen buffaloes to the premises of Nepal Bank Limited in Birtamod.

Alleging mistrust from the bank during his buffalo-rearing endeavors, Prasai staged a “dharna” to express his grievances.

Yet, his inconsistent thoughts and behavior raise questions about his suitability as a public figure claiming to reshape the nation.

Despite his vow to overturn the system through a month-long continuous demonstration in Kathmandu, skepticism abounds.

Whether Prasai is harboring delusions or grappling with a childhood ailment, his ambitious plan appears disconnected from historical precedents.

Even during the Maoists’ 6-day strike surrounding Kathmandu in the past, a government remained untoppled, casting doubt on Prasai’s ability to single-handedly usher in systemic change today.

An unraveling narrative of political ambiguities

Prasai, devoid of any party or organizational affiliation, propounds a rebellion that, according to him, has ignited across all 77 districts.

His declarations swing between visions of a revolutionary change orchestrated by women directing streets from Ratnapark to Baneshwar, and a purported October revolution akin to Lenin’s.

Amid claims of peace, Prasai threatens media exposure for those who challenge him, perpetuating an atmosphere of intimidation and disdain towards critics and opponents.

The model of revolution advocated by Prasai lacks clarity, leaving a void regarding the arrangement that would replace the existing system.

While expressing a desire for a monarchy, he remains ambiguous about its nature, rejecting an autocratic monarchy but failing to outline a constructive alternative.

The absence of documents or roadmaps further adds to the uncertainty surrounding Prasai’s vision for the nation’s future.

Despite acknowledging the indispensability of foreign investment for Nepal’s development, Prasai adopts a confrontational stance, not only against projects like MCC and BRI but also against major business houses, accusing them of being Indian.

Paradoxically, he promises to provide employment to 5 million Nepalis post-system change, raising questions about the feasibility of such plans without foreign investment.

Prasai’s statements are rife with contradictions, such as his declaration to withdraw 20 lakh rupees from the bank on the morning after the king’s return, juxtaposed with MPs’ claims of preparing for a fight after the movement succeeds.

Inconsistencies also emerge in his post-campaign aspirations, oscillating between sitting in Khaptad with garlands and issuing warnings about the return of the former king.

His conflicting stance on wealth and lineage adds another layer to the paradox, as Prasai claims to champion the cause of the poor while boasting about his affluent family background.

This incongruity raises questions about his accountability and the sincerity of his commitment to the underprivileged.

Moreover, Prasai’s historical affiliations, initially with the Maoists, highlight a shift to the Nepali Congress and subsequent involvement with the UML.

His past actions, including violence during the Maoist era, create a moral dilemma, especially as he criticizes others for actions he himself once pursued.

The selective targeting of opposition leaders, particularly KP Sharma Oli, prompts scrutiny into Prasai’s motives and the evolution of his political alliances.

The overarching question remains: Will Durga Prasai adhere to his current ‘royalist line,’ or will he diverge onto a different path in the future?

This inquiry necessitates not just verbal responses but a demonstration of consistent behavior and principled actions.

As Prasai’s assertions on the return of the king as a panacea for the country’s problems face skepticism, his narrative seems to crumble under the weight of its internal contradictions and lack of a coherent vision for Nepal’s future.

Comment