This country has got to decentralize. This is the conclusion of this article. So if you’re busy, read no further – sorry, no, please don’t do that. I’ve already made this effort. Please.

I like to believe that there are only a few places on earth that are as gifted as Kathmandu. It has equally spaced out seasons – not too hot – not too cold.

It is rich in culture. There are countless world heritage sites. The land is fertile. The valley is draped with rivers. If preserved, Kathmandu has everything to make an exceptional fat-man Travel & Living show, except, it is dying.

It has now morphed into a city that’s dissolving into a sewer. But the sad part is – it’s irreversible.

I was chatting with my relatives the other day whose, since their great-grandparents, were all born and bred in Kathmandu, and they were going on about all the vast lands their ancestors owned back then.

Well, what’s the point of saying that now? Now, most Kathmanduites have reduced their possession to a prehistoric disintegrating house with a garden that you need to squeeze through.

When you sneeze inside your house you blow out a dome of novel coronavirus shockwave in your neighborhood. C’mon, brag about your ancestors’ land when you actually have something to give to the new generation.

But one thing that makes me jealous is how the older generations share stories of Kathmandu just a few decades ago and describe it as a paradise.

And I believe them. I’ve seen photos of Kathmandu from the 1960s to the 1980s and the monochromes tell a splendid tale.

My mom tells me how all the rivers were much wider and pristinely clean. Now, I pinch my nose as I approach any river within 100 meters of it.

Now that I’ve said that, every politically savvy middle-aged wise man in jeans and white snickers will boldly claim that even if people don’t want to live in Kathmandu, they have no choice given that convenience is key.

It’s not a river anymore. It’s all sewage. Sometimes I wonder if climate change is to blame. Maybe the warming climate is melting all the frozen prehistoric ooze in the Himalayas of what’s left of exotic creatures that were squashed during the collision of the Indian and Eurasian continental plates 50 million years ago.

Then I remember when I was a child, at least the main streets of Kathmandu had working street lights.

But now you see bundles of taxpayer money ripped apart with those broken low-budget solar street lights that cause more darkness with its shadow than light up the street. What’s the point!

Then you have the crowdedness. I remember playing in open fields as a child. But now every square foot has been divided up and sold separately.

And whoever buys the land erects a 10-story building with a foundation the size of a coin squeezed between two other matchbox houses literally so close that you smell the armpits of the neighbors.

I know what the problem is – and it was confirmed by my pretentious academic relatives the other day. Kathmanduites are just too lazy, while everyone else from the corners of the country dreams of owning a house in Kathmandu because it’s considered a pinnacle of achievement.

Now that I’ve said that, every politically savvy middle-aged wise man in jeans and white snickers will boldly claim that even if people don’t want to live in Kathmandu, they have no choice given that convenience is key.

They’re right. You may wish to live somewhere else, but for every single necessity, Kathmandu is a focal point. Unless you have your own logistics van, a driver, and a middle-man who knows how to smoothen relations with government officials, you will find it difficult to settle permanently outside Kathmandu.

Local and provincial governments will also run effectively. Books will reach every child in remote areas, so the quality of education will get better and our development will decentralize.

But unlike the middle-aged man in jeans and white snickers, I also come up with solutions. I propose to turn Kathmandu into a massive logistics handling city and make every building a warehouse.

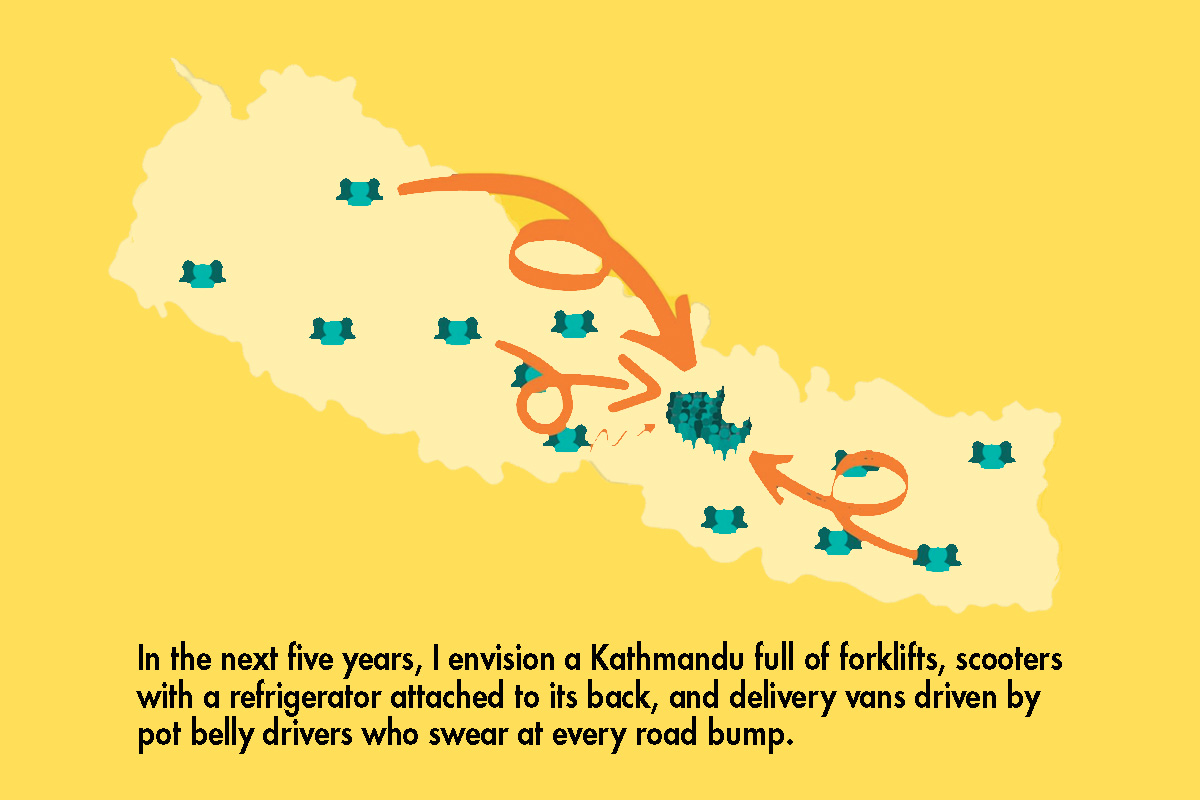

Then let’s incubate some 5,000 logistics companies who deliver all over Nepal – and I seriously mean ‘all over Nepal’, which includes even those corners of the country where our citizens are confused whether they are Nepalese or Indian.

Having 5,000 logistics companies will create a healthy competition that means great service and I guarantee that at least two of them will survive in the next five years.

Local and provincial governments will also run effectively. Books will reach every child in remote areas, so the quality of education will get better and our development will decentralize.

So, in the next five years, I envision a Kathmandu full of forklifts, scooters with a refrigerator attached to its back, and delivery vans driven by pot belly drivers who swear at every road bump.

Right now, I can only wish to move out of Kathmandu knowing very well that if I need a cell phone charger, the shopkeeper in Darchula will refer me to a shop in Ason and all I need to do is travel 900km two-day one-way trip.

(Views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Khabarhub’s editorial stance)

Comment