“Rajendra Sir, you are a personality who worked in the secretariat of the Council of Ministers, which was established under the leadership of Chief Justice Khilraj Regmi, who led one of the most successful and powerful governments in history. Why is someone who once worked close to the center of power and authority inside Singha Durbar now wholeheartedly dedicating their heart, soul, and energy to a small institution in a rural village?”

This question from Yadav Chandra Niraula, Undersecretary at the Ministry of Education and Head of the Library Coordination Branch, was not an ordinary one. It was the same curiosity that colleagues and well-wishers had frequently raised, and one evening during last year’s Sudurpaschim Conference in Attariya, it stood before me. I couldn’t resist this time. I needed to unpack the deep, unbreakable bond I have with libraries.

I said, “The Matribhumi Library is a sacred gift from my father, Sir. It is not merely a room filled with books—it is the very foundation of my existence. From the very beginning of my childhood, that place was the source of the first light of consciousness and awareness. It served as more than just a place to store books; it was a place infused with the passion, sweat, tears, and dreams of the generations that came before us.”

“Living detached from that legacy, which was created with such sincere sacrifice of one’s body, mind, and resources, would be living an incomplete life. It is an honorable heritage that is deeply rooted in the ground where I was born.”

Tony’s Footsteps in Birgha

My first connection with a library took root in my birthplace, Birgha, in the courtyard of the Matribhumi Library. The library born after democracy was not just a building; it was the first light of freedom that gave our village a new life. That courtyard was also the site of my early education. I used to go to Janata Primary School in grade three at the time.

As a result of those conferences, provincial committees were established, proclamations were made, and a culture of listening to libraries’ voices began to emerge.

The memory of that day is still as vivid in my mind as it was yesterday, and every time I think back on it, an unfathomable flow of happiness fills my heart. Antonio Neuber, an American citizen who is fondly known as “Tony,” traveled to our hometown with her team in order to assist in guiding Matribhumi Library toward growth and success. Ready to greet them, we children stood with garlands in our tiny hands, full of the naïve excitement of our young hearts.

A dream so vast and precious was brought by those foreign visitors—unfamiliar yet oddly cozy and intimate—to illuminate our village and turn it into a hub of knowledge and education. With garlands in our tiny hands and the innocence and enthusiasm of our young hearts, we children stood ready to welcome them.

These foreign visitors, who were strangely familiar yet intimate, brought with them a dream so big and priceless: the dream to light up our village and turn it into a hub of learning and understanding.

Tony is no longer with us today. And I, too, have come a long way since my innocent and joyful childhood. The Matribhumi Library, Tony’s legacy, and the priceless memory rooted in my impressionable mind are all that remain. That memory gives me strength and inspires me to make a lifelong commitment to education and libraries.

Tony used to visit Nepal almost every year. In 1991, she visited the village of Junbesi in Solukhumbu. Domi Sherpa, her guide in that quiet, peaceful village nestled in the Himalayas, supported her throughout the journey. At the end of the trip, Tony smiled and said, “You’ve helped me so much; now I’d like to do something to help you.”

“Our village still has a very weak reading culture,” Domi said simply. “The villagers might have access to reading if we had a modest structure to house the books.”

Tony was touched by that innocent suggestion. A new chapter in her life began with those very words. She started the community library movement and founded the international organization Rural Education and Development in the same year. That same year, Junbesi saw the establishment of its first community library. It marked a turning point in history as Nepal’s community libraries began their journey.

After that, the Matribhumi Library was established. Gopal Dai from the village had this big dream, and with the continuous support of the village’s educational and political leaders, it eventually became a reality. But the most important factor was Tony’s unwavering dedication and presence, which kept the movement alive. She devoted her precious time to spreading the light of education and knowledge throughout the village.

The village’s everyday routine changed when the library opened. For everyone, from young children to the elderly, holding and reading new books became a kind of celebration of life. We always looked forward to the school bell ringing at one o’clock and wondered if we would have the opportunity to visit the library during lunch. The thrill of turning the pages and immersing oneself in the world of books—even putting hunger and thirst aside—was unparalleled.

By the time I reached my School Leaving Certificate (SLC), my bond with the library had not weakened; on the contrary, it had become even stronger. In my life, the three main pillars were the library, school, and home. My love of books and my village upbringing may have been the reasons I made it all the way to Kathmandu. I continued to visit the British Council, look through new books, and make reading a daily habit even after I had moved to the capital.

The Transformation of Matribhumi Library

I usually enjoyed reading and going to the library. But I never thought that one day I would have to stand under my own leadership, carrying so much responsibility. I approached my campaign with a single ambition in mind. Through my experience with the Matribhumi Library, I have learned that some responsibilities arise unexpectedly—and they can become life-changing experiences.

My father was not only the headmaster and resource person at Janata Secondary School, but he also became the chairperson of the Matribhumi Library after his retirement. He kept repeating one sentence to me for as long as he had breath: “Protect and build Matribhumi.” That sentence has become a lifelong mantra for me.

The Matribhumi Library was instantly reduced to rubble by the devastating 2015 earthquake (2072 B.S.). My father immediately prioritized rebuilding the library. However, in a strange and poignant coincidence, my father also passed away on the 12th of Baisakh, exactly three years after the earthquake. I was determined to carry out my father’s last wishes when the village elders entrusted me with the library’s management. Like the voice he used to repeat when he was alive, a strong, invisible energy stirred inside me: “Protect and build Matribhumi.”

Ensuring the library’s continuity was a more difficult task than simply rebuilding it into a new structure. Nevertheless, collaboration and support came together. With the unwavering support of the Government of Japan, the financial assistance of the Peace Volunteer Association, and the technical partnership of READ Nepal, this dream was realized.

Matribhumi: The Seed (Beginning), A National Movement: The Tree

I became even more devoted to the Matribhumi Library after taking on its leadership. Despite having a background in journalism and media from both my education and employment, I didn’t fully understand that this was no simple task until I took on the role of leading our village library. Lighting the lamp of knowledge for upcoming generations became my goal.

But at first, I had a lot of questions. I used to often wonder, “Why am I enjoying a small village library when my classmates are spending their time in some of the most prestigious libraries in the world? Am I headed in the right direction?” I wasn’t sure for a while about those questions. Eventually, however, a clear response surfaced from within:

“This is more than just my father’s dream. Protecting it is not only about keeping Matribhumi safe. This is a nationwide effort to protect the nation’s many community libraries.”

That belief inspired me to begin a larger, nationwide campaign. I was given the responsibility of stepping in as General Secretary at the Nepal Community Library Association’s general assembly in Chitwan during Bhadra 2079 B.S. (August/September 2022). The Matribhumi seed became the tree of a national movement at that very moment.

Since then, conferences organized in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology have taken place in each of the seven provinces. In all of them, I took an active part. Everywhere I went, I had the chance to gain a thorough understanding of the challenges, requirements, and potential of the local libraries.

I was most surprised to learn that this library was more than just a collection of books. It served as a gathering place for culture and consciousness and a hub for community. From language classes to digital archives, children’s reading programs, exhibitions, and technology workshops, the library was creating innumerable connections that bonded people and bolstered communities.

As a result of those conferences, provincial committees were established, proclamations were made, and a culture of listening to libraries’ voices began to emerge. I can now confidently state that the little seed that was sown in Matribhumi has developed into a nationwide movement. Its roots are the community’s trust, its branches are the hopes of generations, and the knowledge of the future flutters on each leaf.

An Incredible Experience at the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library

When I was in school, our teachers used to ask during quizzes, “Which is the largest library in the world?” I used to leap out of my chair and respond with pride, “The Library of Congress, America.” When the teacher said, “That’s right,” I would feel like I had won the world. I used to think that Kathmandu was as big and far away as America. It was unimaginable to ever travel to America, much less enter one of its magnificent libraries.

But even the impossible is achievable in life when one is committed and dedicated. From an early age, Tony, an American, had sown the seeds of knowledge and wisdom in my mind, which kept the idea of America in my thoughts. I never imagined that the awareness she planted would spread through the generations and eventually get me into some of the most famous libraries in the world.

My engagement with libraries and the culture of reading was strengthened by my participation in the Community Library Association. Elevating the significance of National Library Day in Nepal was made possible by our continuous efforts to increase the visibility, impact, and accessibility of libraries. And I received confirmation of my trip to the United States just as the 17th National Library Day celebrations were coming to an end.

I was in the United States for the second time. About a month and a half had passed since my first visit, during which I had visited many cities and interacted with a diverse range of individuals. This time, though, I had a different goal in mind: to experience, sense, and absorb the essence of libraries.

I made sure my thirst for knowledge was satiated as soon as I set foot in the United States. Coincidentally, I had the privilege of representing Nepal as a delegate and guest speaker at a significant United Nations conference on libraries, in addition to having the chance to tour two famous and historic libraries: the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress.

This trip was not just an opportunity to experience travel from a tourist’s point of view. It turned into an intensely contemplative experience that allowed me to think carefully about the value of libraries, their influence, and their unmatched contribution to human civilization. While I was inside those massive institutions, I realized: a library is not just a building—it is the backbone of civilization.

New York Public Library: The Soul of the City

The New York Public Library, which is in the center of New York City and is frequently referred to as the city’s soul, was my first destination when I arrived in the United States. Through the chaos of the city’s constant motion and the never-ending buzz of New York’s 24/7 energy, I made my way to its entrance.

I spent almost six hours exploring the library’s different departments with John and Ron, two staff members. I gained more inspiration and energy with each step. Inside, readers were completely absorbed in their own worlds; nobody disturbed anyone, and the silence of the room was unbroken.

There, two grand stone lions stood tall—“Patience” and “Fortitude”—eternal symbols of resilience and strength, welcoming me. In that instant, it seemed as if entering a library was equivalent to entering a palace of knowledge, an experience that is impossible without courage and patience.

I had visited this location previously, but only as a tourist, taking a few pictures and leaving. But this time, I felt a much deeper connection to the location.

When I stepped into the magnificent Rose Main Reading Room, with its soaring ceilings that seemed to reach the sky, breathtaking murals, and people studying quietly in perfect discipline at long wooden tables, I felt as if I had entered a sacred space, a temple of learning.

It wasn’t just a room full of books; it was a place where I could discover new ways to understand life, refine my soul, and make sense of my existence.

I was most surprised to learn that this library was more than just a collection of books. It served as a gathering place for culture and consciousness and a hub for community. From language classes to digital archives, children’s reading programs, exhibitions, and technology workshops, the library was creating innumerable connections that bonded people and bolstered communities.

I became distracted as Zena, a senior officer at the library, talked about her experiences. I was unaware that half the day had gone by. I was utterly enthralled by this rich world of knowledge and culture.

Library of Congress: An Ocean of Knowledge

When I finally arrived in Washington, D.C., after a three-day journey from New York, a lifelong dream that had been present since childhood was about to come true—seeing the Library of Congress, the world’s largest library.

As I made my way to the Jefferson Building, I had the impression that I was entering the very womb of time itself rather than just any building. The shining dome reflecting the glimmer of leaves, the white marble stairs, and the paintings depicting civilization’s history all seemed to me to be living miracles. A voice inside of me whispered, “Knowledge is power—but it is not just power, it is beauty.”

Instead of being in a building made of books and paper, I had the impression that I was inside a living temple made of philosophy, history, and humanity. There were more than 170 million objects, including books, maps, manuscripts, audiovisual treasures, rare works of Shakespeare, early American court documents, and knowledge from around the globe, all of which were resting in silent meditation.

My objective was very clear when I set out on my journey to the U.S.: I wanted to see the most famous libraries in the world, get a close-up look at them, and have meaningful discussions with people who have devoted their lives to this mission.

The opportunity to sit inside the Main Reading Room, which is revered as a sacred place of knowledge by scholars around the world, was the most emotional moment. Sitting quietly in the center of the circular hall, surrounded by towering shelves like mountains of wisdom, with golden light gently filtering in through the glass above, and readers immersed in complete silence, I felt as if I had joined an intellectual journey spanning centuries. The smell of old paper and ink made me feel like I belonged to an ancient scholarly tradition.

While sitting there, it felt as if time was slowly passing, but knowledge remained still, eternal, and timeless.

I spent almost six hours exploring the library’s different departments with John and Ron, two staff members. I gained more inspiration and energy with each step. Inside, readers were completely absorbed in their own worlds; nobody disturbed anyone, and the silence of the room was unbroken.

Beyond the actual collection, however, this library’s true magic lay in its very presence. In addition to being architectural experiences, standing beneath the enormous dome and touching the brass railings that had been polished by generations of hands felt like sacred, life-giving moments.

As I stepped outside, my heart said, “A library is more than just a room full of books; it is the guardian of civilization.” It is a safe haven for ideas. It is the starting point for a better future.

A quiet question echoed in my mind: “What if we could build such a library in Nepal—a place with this kind of atmosphere?”

Capturing Inspiration from the Temple of Consciousness and Wisdom

I learned a valuable lesson and had a profound experience on this journey that will last a lifetime. I realized that a library is a living institution of civilization, culture, and community—not just a repository of books.

What truly distinguishes a library are its pillars: open access, cutting-edge technology, diverse cultural programming, genuine hospitality, and a deep respect for all visitors. These were clearly visible at the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library.

After the encounter, I felt more energized and confident to take a fresh look at Nepal’s libraries. Incorporating technological, accessibility, and infrastructure innovations into our libraries is still necessary, but our nation also has a rich history of community life and historical heritage.

Nepal’s community libraries will eventually become world-class models if we can rethink the concept of a library as a hub for education, empowerment, and social change rather than just a “reading space.”

The Dignified Platform Gifted by the Library

Although it is not new, my relationship with libraries has been surprising. I have decades of experience in the field, but I am neither a library science expert nor a student. What I have discovered, though, is that the absence of formal experience will never be an obstacle if you have unwavering determination and put forth endless effort.

I thought of my father, whose guidance, affection, and blessings have served as the foundation of my life. I thought of Tony, whose encouragement, faith, and support got me this far. I also thought of Matribhumi, whose earthy aroma permeates every breath I take.

My objective was very clear when I set out on my journey to the U.S.: I wanted to see the most famous libraries in the world, get a close-up look at them, and have meaningful discussions with people who have devoted their lives to this mission.

Meetings had already been planned with colleagues from the American Library Association in that context. I had the opportunity to meet Loida, a global library advocate who works with the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), at that time.

When we first met, I asked her, “What made you choose this field?” I was astounded by her response because her story was exactly like mine. To fulfill her mother’s dream, she had also pursued this career path. And I, to fulfill my father’s dream. That’s when our professional conversation turned into a strong emotional bond.

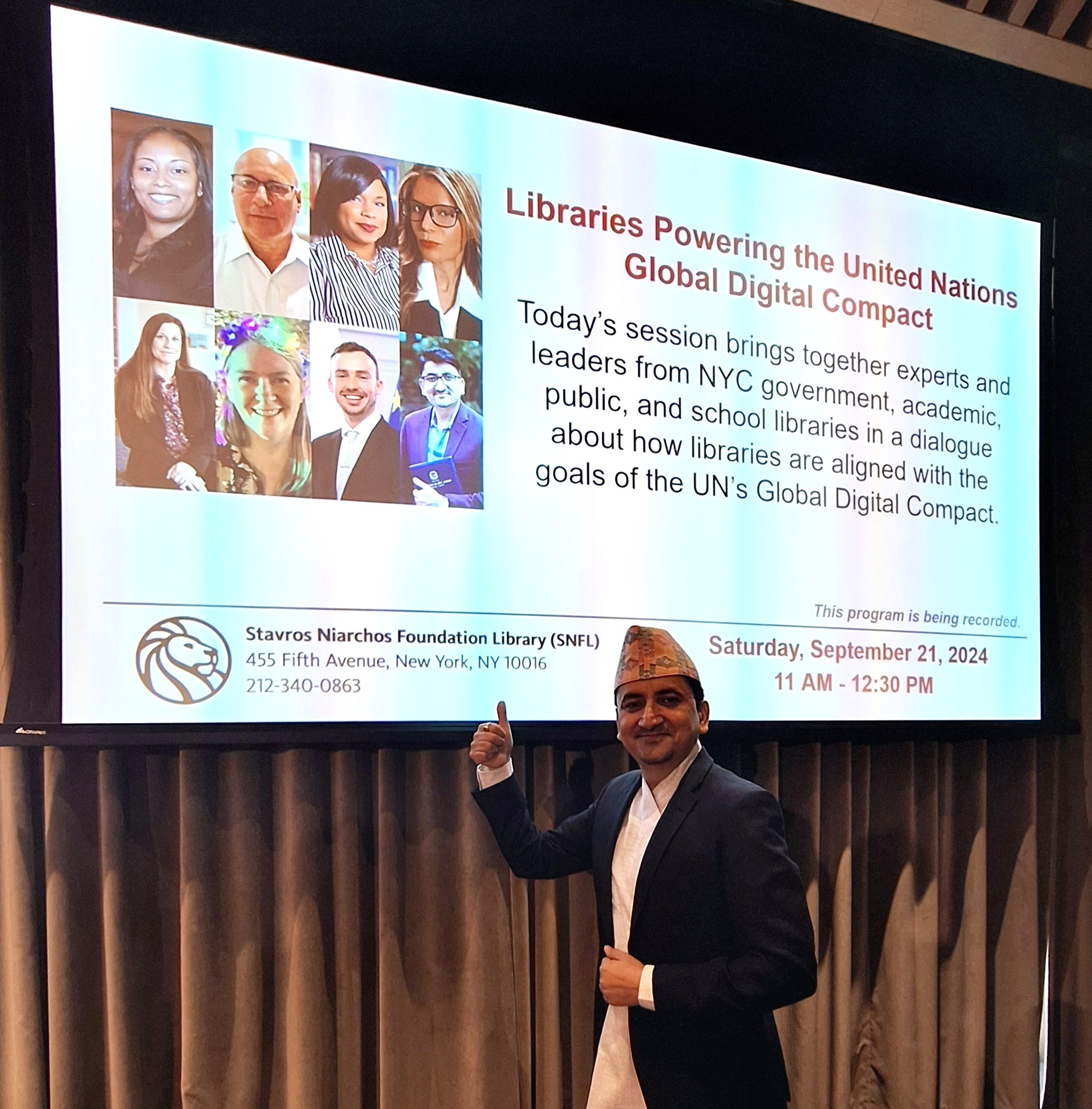

Influenced by Nepal’s public and community libraries, Loida made the amazing suggestion that I participate as a guest speaker in a panel discussion called “Libraries Powering the United Nations Global Digital Compact,” organized by the American Library Association and coinciding with the 79th United Nations General Assembly.

September 21, 2024—a day that will always be remembered, a turning point in my life. I was one of the guest speakers on that global stage with Ireland’s Permanent Representative, Carl Redmond. With specialists having in-depth and thoughtful conversations, the discussion focused on how libraries worldwide can contribute significantly in the digital era.

In my speech, I shared the story of Nepal’s library development from the beginning to the present. I talked about the necessity of digital libraries, the need to give everyone—especially those with disabilities—equal access, and the challenges that lie ahead. “This journey has started in Nepal, but there is still a long way to go,” I remarked. I could tell people were paying close attention by the expressions on their faces. Inquiries about Nepal’s community libraries were common after the program.

My heart silently went back to my own village as I stood on that magnificent stage, thousands of miles away across the oceans. As I read the participants’ expressions, a sudden mist seemed to blur my vision. Memories of my early years started to dance inside me.

I thought of my father, whose guidance, affection, and blessings have served as the foundation of my life. I thought of Tony, whose encouragement, faith, and support got me this far. I also thought of Matribhumi, whose earthy aroma permeates every breath I take.

I remained silent for a few seconds. No Tony was present, and no father was there to share in the happiness of that proud moment. I missed the people I wished to share my success with in the middle of New York’s busy streets, where everyone was hurrying to get where they were going.

“Ba, your Raju has come this far,” my heart kept yelling. I am where I am now because of your guidance and faith in me.

Finally, I gathered myself and told myself, “This experience is not just a professional achievement; it is a confluence of dreams, memories, and gratitude that will echo in my soul for eternity.”

Comment