KATHMANDU: When Pasang Nuru Sherpa recalls his childhood in the quiet village of Pangboche, in the foothills of Sagarmatha, the Nepali name for Everest, his memories take him back to the gentle hum of daily life: the swishing of prayer flags, the calls of mountain birds, and the soft clink of yak bells as the animals meander along the narrow trails.

Back then, any disruption to this silence was rare, signaling either an emergency medical evacuation or the arrival of a high-profile visitor. Both were reasons for a helicopter to approach the homes of the Sherpa people, renowned for their ability to thrive on the world’s tallest mountains.

Today, however, the choppers have become ubiquitous. Their duty now extends to serving “helicopter tourists,” the name given to affluent tourists who want an instant ride up nearly all the way to Base Camp and are willing to pay a premium for it. “The sound of helicopters never stops,” Pasang says. “They start flying at 6 a.m. and don’t stop until sunset. It disrupts our lives.”

It’s more than just the noise; the air traffic has taken an economic and social toll on Pasang and his community, while also endangering the fragile ecosystems of their homeland already under stress due to rising temperatures. Residents say much of the profits from helicopter tourism end up with the operators, often based in Kathmandu or abroad, leaving local Sherpas to face the consequences and costs.

Reaching the Base Camp of the highest peak on Earth typically requires a minimum 14-day trek, often led by guides and filled with physical and spiritual preparation. But now much of the hard work can be shortened to a matter of hours for those willing to pay between $1,500 and $2,000 for a helicopter trip. The chopper takes tourists straight from Kathmandu, with a pit stop along the way at Hotel Everest View, located in Syangboche (elevation 3,780 meters, or 12,402 feet), a small settlement above Namche Bazaar, the main gateway to Sagarmatha from the Nepali side. (The mountain can also be scaled from the Chinese side, in Tibet, where it’s known as Qomolangma.)

Companies also offer chartered flights starting from $5,000 that go even higher than Base Camp, to Kala Patthar, the viewpoint to see Sagarmatha from up close.

This facility for tourists to get close to the scenic mountain and savor its views while bypassing the grueling trek up to Base Camp represents a paradigm shift in the country’s tourism industry, helicopter operators say. Pratap Jung Pandey, first vice president of the Airline Operators Association of Nepal, says affluent tourists with limited time couldn’t get the “Everest experience” in the past, but now they can, thanks to the helicopter service.

Pandey also says the operations are in compliance with government regulations, including those set by the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal (CAAN) and Sagarmatha National Park (SNP).

That hasn’t quelled protests by local communities, which have prompted the national park authorities to suspended helicopter flights in the region. Park authorities along with the local municipal government have also proposed changes to existing rules to ban non-emergency flights in the region.

Sherpas feel the pinch

With its harsh climate and rugged terrain, the Sagarmatha region has always been a challenging home for the Sherpas who traditionally relied on rearing livestock and trade with Tibet for their livelihoods. But with the arrival of adventure tourism and trekking, communities spread across different settlements in the Khumbu Valley region at the foot of Sagarmatha — including Tengboche (3,860 m/12,664 ft), Pangboche (3,985 m/13,074 ft) and Namche (3,440 m/11,286 ft) — saw their livelihoods change as thousands of people from all over the world started to pour in.

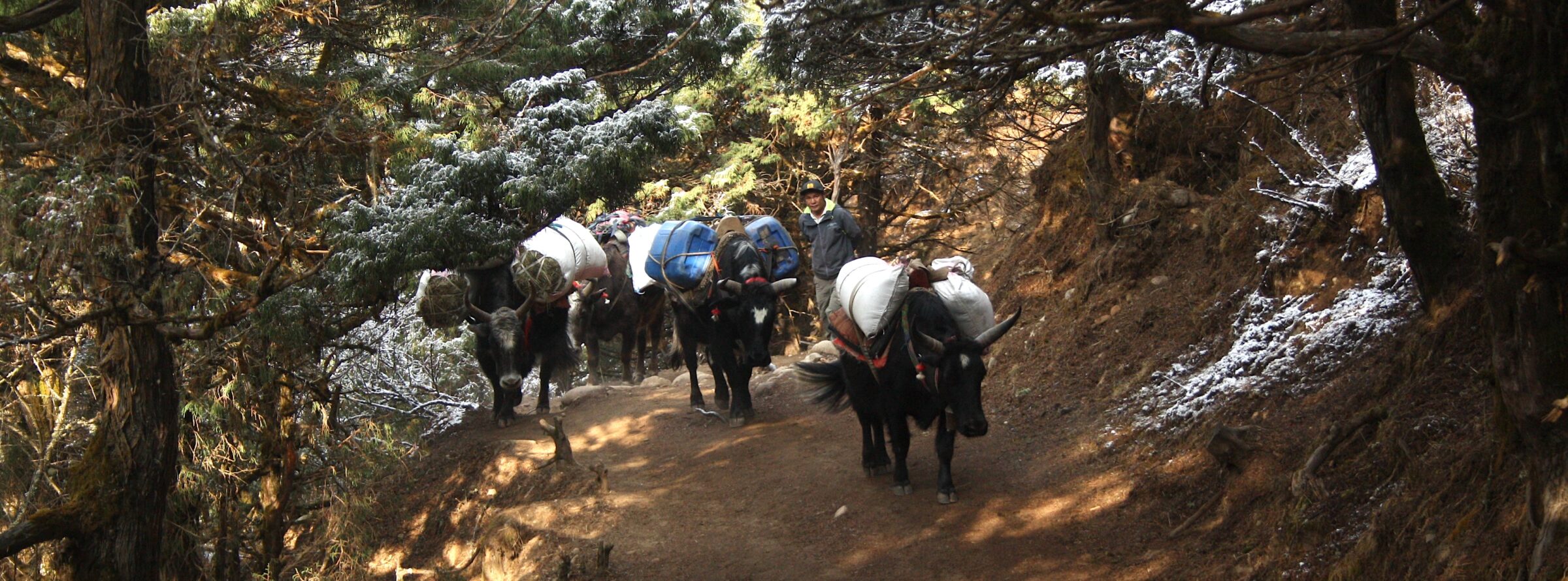

The helicopters are the latest arrivals, but they bypass iconic trekking routes in the Khumbu Valley, including Namche Bazaar, the gateway to Sagarmatha; Tengboche, home to one of the largest monasteries in the region; and Gorak Shep, the last stop before Base Camp (5,364 m/17,598 ft). These were places once abuzz with trekkers engaging deeply with the local culture.

In 2024, there were more than 5,600 helicopter flights recorded in the region, according to Sagarmatha National Park information officer Bibek Baiju, with some days during the peak trekking season (April-May and October-November) recording nearly 100 flights daily between 6 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Porters carrying gear and supplies for trekkers say they feel the pinch the most as their earnings have gone down. “We have observed that the longer the trekkers stay with us, the more tips we get,” says Tenzing Bhote, a porter from Lukla, home to the region’s one and only airport and the starting point for the trek to Base Camp. “Now, with trips being shortened to seven days, our income is much lower,” he said.

According to the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, 57,690 people visited Sagarmatha National Park in the 2022/2023 period. That was more than double the 26,492 visitors in the previous period. With each helicopter carrying an average of two tourists, that translates to an estimated 11,000 people (two out of every 10 trekkers) taking a chopper. Figures from the airline operators’ association also indicate that around 20% of trekkers use helicopters to either fly into or out of Sagarmatha National Park.

Also left out of this aviation boom are local Sherpa women, who play a critical role in managing the mountain’s lodges and gift shops.

“We prepare for months, stocking food and supplies, but when tourists fly out quickly, much of it goes to waste,” says Pasang Sherpa, president of the Khumbu Women’s Committee. “We need to understand tourists spend more on their way back, and when they don’t trek back, our income is hit hard.”

With fewer tourists spending extended time in the region, the local economy is experiencing a ripple effect that impacts families, small businesses and cultural preservation efforts, says Sonam Sherpa, a youth activist advocating against helicopter tourism.

Beyond financial losses, the personal bonds that often formed between trekkers and the Sherpas — sometimes leading to long-term support like sponsoring of their children’s education — has also weakened, residents say.

There was a time when trekkers stayed for weeks, forming deep connections with the local culture that left long-lasting impacts on both the hosts and the guests, says Mingma Sherpa, a lodge owner at Namche Bazaar.

“They used to come for the journey,” he says. “Now, when coming down from the mountain, many prefer to fly out from Gorak Shep,” which is closer to Base Camp than Namche.

Pasang Nuru Sherpa from Pangboche says the fast-paced nature of helicopter tourism leaves little room for cultural exchange, further distancing visitors from the unique traditions of the Khumbu region. He says the region’s Sherpa culture, deeply rooted in Buddhist traditions and a reverence for the mountains, is becoming increasingly commercialized as tourism grows.

“Ceremonies such as the puja, a prayer ritual performed to bless climbers before expeditions, have become mere spectacles for tourists rather than meaningful spiritual practices,” he says.

Sonam Dorjee shares a similar sentiment: “The special connection we had with visitors is disappearing,” he says.

The environmental consequences

Helicopter tourism is also potentially disrupting the fragile ecosystem of the Himalayas, an area already vulnerable to climate change, says Sudeep Thakuri, a climate scientist.

“While there is no research on the ecological damage caused by helicopters in the region, the number of helicopters flying in the region obviously has an impact as they emit a lot of CO2 and disturb the wildlife in the region,” he says.

Residents also say the noise pollution caused by frequent helicopter flights is driving wildlife, including snow leopards (Panthera uncia), Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus) and musk deer (Moschus leucogaster), away from their natural habitats.

“The locals’ concerns are valid, as the Khumbu Valley is very narrow, which amplifies the noise. This does have an impact on both the wildlife in the area and the livestock,” Thakuri says.

While studies on this specific issue in Nepal are limited, researchers say they believe helicopter tourism could already be taking a toll on the iconic yet vulnerable snow leopards. Researcher Bikram Shrestha, who has studied the big cat in the region, says that as snow leopards are nocturnal animals, they might not be directly affected by daytime chopper flights. But he says he’s seen Himalayan tahr, a large goat-like animal that’s the prime prey for snow leopards, run away due to helicopter noise.

“This could have an impact on their reproductive success and in turn the availability of food for snow leopards, the apex predators of the mountains,” said Shrestha.

Studies conducted in high-altitude ecosystems, such as those in Alaska and the Alps, have found that noise pollution disrupts animal behaviors such as feeding, mating and migration. A study in the Alps showed that frequent helicopter noise caused a significant reduction in the grazing behavior of mountain goats, leading to decreased food intake and an increase in stress. In Alaska, a study carried out for the U.S. Army showed that when helicopters flew 100 meters (330 feet) above the ground, polar bears (Ursus maritimus) would flee up to 64 kilometers (34 miles) away and spend significant time away.

Back in Nepal, even domestic yaks (Bos grunniens) may be affected. Traditional herders say they’ve noticed increased agitation among their animals. Yaks are vital for local communities here, where they’re used for transporting goods and providing milk and manure — essential services for farming in this high-altitude region.

This aligns with findings from a 1991 study that indicates that helicopter noise and other disturbances can cause heightened agitation and behavioral changes in both livestock and wildlife. The study further suggested that aircraft-related disturbances may decrease food intake in animals.

“Our yaks are vital — not just for milk but for manure, which is essential for fuel and farming,” Pasang Nuru says. “If yak herding is affected, it’s not just an economic loss; it’s also the loss of a cultural tradition.”

In addition to the strain on wild animals, helicopter noise could have severe repercussions for the fragile mountains and glaciers, already under stress from rising global temperatures, says Thakuri, the climate scientist. Frequent movement of aircraft could potentially increase the risk of avalanches and landslides, especially in areas where helicopters fly close to the ground, he says. Locals still remember the recent destruction of the village of Thame by glacial floods, and say they worry that increased helicopter activity could aggravate such disasters.

“Who’s to say it won’t happen again with helicopters flying so close to the mountains?” asks Sonam Dorjee Sherpa, the youth activist.

Even before tourism took off as a major enterprise, local communities were already bearing the cost of living in Sagarmatha National Park since it was established in 1976. As a protected area and UNESCO World Heritage site, Sagarmatha is subject to various restrictions, such as limits on construction of houses, felling of trees, and laying of power lines, all aimed at conserving the natural ecosystems.

While the local communities bear such immense costs of instant tourism, they don’t have a share in the profits, says Mingma Sherpa, the Namche lodge owner. “The money is leaving Khumbu,” he says. “The helicopter companies profit, but we are left with the consequences.”

A report prepared by local residents with support from the municipality of Khumbu Pasang Lhamu showed that less than a fifth of the hourly fee of 145,000 rupees ($1,050) for an Airbus H125 helicopter operating in the area remains within the national economy — and that’s only if the pilot is Nepali. Economist Arjun Dhakal, who specializes in natural resources, says the number sounds plausible, given that a large chunk of the revenue goes toward repayment of loans taken out by companies to buy the aircraft, pay for insurance and cover operating costs, including fuel.

“This shows that helicopter tourism is not beneficial for both the local as well as national economy,” he says.

The operators do pay a $21 fee to the national park for every flight, but that’s hardly enough for the damage they cause, say local community leaders, who argue that the ideals of ecotourism — sustainable travel that benefits both nature and communities — have been cast aside in the pursuit of quick profits.

Mingma Sherpa says many tourists opt for helicopter rides to save time, but this fast-paced tourism model undermines the region’s long-term sustainability vision for ecotourism practices that ensure a win-win for development as well as conservation.

“Helicopters may bring in more tourists, but they don’t bring sustainable development,” he says.

Mitigating impacts

Recognizing the growing impact of helicopter tourism, local communities are taking a stand. Youth groups in the region have staged protests, blocking helipads and demanding stricter regulations.

Municipal officials from Khumbu Pasang Lhamu are also advocating for policies that limit flights, reroute them away from sensitive areas, and ensure that tourism profits are distributed more fairly among local communities.

“We need balance,” says Pasang Nuru Sherpa. “The helicopters aren’t going away, but if we don’t manage their impact, we risk losing everything: our culture, our peace, and our way of life.”

Helicopter operators say their services aren’t the primary cause of environmental or cultural disruption in the Sagarmatha region. Pandey from the airline operators’ association acknowledges the problems caused by the noise, saying, “We will try to address these concerns, but variable weather conditions sometimes force us to fly at low altitudes.”

He says helicopter transport plays a vital role in the region, supporting the transportation of food, construction materials and emergency medical rescues. “Without us, even basic logistics in such a harsh region would be challenging,” he says.

Pandey adds that some of the criteria imposed by local authorities in response to the protests over helicopter flights, such as rerouting flights away from sensitive areas, are difficult to meet under current operational needs. He says that if helicopter services are limited only to rescue operations, the government would need to take over the operations entirely, and pay proper compensation to the operators.

“We have advance bookings made six months to a year prior to a flight. This protest by the locals has forced us to cancel flights,” says Pandey, who’s also the managing director of Kailash Helicopter Services Ltd., one of the 11 helicopter companies flying the route.

While the operators agree that climate change is a significant issue, Pandey says helicopter emissions contribute minimally to environmental degradation. Instead, he calls for a balanced approach that allows for both tourism and sustainability, emphasizing that “helicopters are a lifeline in this region, not just for tourists but also for locals.”

Back at his village in Pangboche, Pasang Nuru says he longs for those quiet days when life was simpler for the Sherpas. He also acknowledges that the helicopters are a necessary lifeline to the region, but says they shouldn’t be used for fancy instant parties for the rich.

“We’ve lost our peace, parts of our culture are at risk, and we have lost the connection we once shared with the mountains and the people who came to see them,” he says. “All we are saying is that we want to get back those days.”

This story first appeared on Mongabay and Khabarhub is republishing it under a Creative Commons licence.

Comment