The context in which we discuss change, development, and democracy often brings to light troubling realities. Despite frequent political transitions and claims of progress, our conversations about good governance, development, and leadership remain incomplete without acknowledging critical issues—such as the disregard for public sentiment, the lack of promising indicators, and the prevailing sense of despair.

Which period in our history can truly be called an era of good governance? Why has our development failed to parallel that of other contemporary nations?

Why has leadership not matured, even after our long journey through feudalism, monarchy, democracy, and republicanism? These questions continue to challenge us.

Throughout our political history, major events unfolded and constitutions came and went. We transitioned from dictatorship to a parliamentary system, only to fall back into monarchical autocracy under a non-party regime.

Eventually, the multi-party system returned. Yet again, we were caught in the turmoil of royal rule. After enduring such upheavals, we finally reached the Constituent Assembly within a republican framework. However, democracy failed to gain stability or deliver its expected benefits.

Even after experimenting with various electoral systems—including a mixed model of direct and proportional representation—elections failed to ensure meaningful representation. They neither produced clear mandates for governance nor established the foundation for stable, recurring electoral processes.

Policies and institutions were often adopted impulsively—more as a gesture toward modernity or progressivism than as tools for meaningful transformation. Little attention was given to whether these ideas could actually work within our own context.

As a compromise, legal provisions allowed parties to form coalition governments. However, this paved the way for unprincipled alliances, fostering a culture of political opportunism.

Parties released lengthy manifestos during elections, but whether these were intended to inform the public or merely to serve as symbolic, non-binding promises remains unclear.

When political parties become entrenched in vested interests and fail to represent the aspirations of the people, multi-party democracy cannot thrive by default.

If these parties do not function as effective agents for implementing constitutional values or advancing democratic ideals, their internal dysfunction—marked by unhealthy competition, lack of accountability, and incompetence—may become symptoms of democratic decline rather than steps toward progress.

Parties, which should serve as platforms for cultivating leadership, risk becoming tools for personal gain, centers of undue influence, and sources of public disillusionment.

Without internal good governance, they lack the moral authority to hold other institutions or the government accountable. A refusal to engage in self-reflection or internal reform makes parties more likely to serve narrow interests rather than the public good.

Today, we see a situation in which representatives are elected—some through technical mechanisms—but leadership remains uncertain. In what is supposed to be a system of accountable governance, many elected officials rarely engage meaningfully with their constituents. When they do, their engagement is often limited to a narrow circle of supporters.

There are few mechanisms for citizens to voice concerns or for representatives to listen. Without well-structured relationships between the state and the people, how can the state truly feel responsible?

If elected officials act as though they have inherited unchecked authority from voters, then it appears the people’s sovereign rights are being sidelined. Sovereignty must reside with the people, and that includes the right to question their representatives and the state itself.

But if citizens are only expected to obey while representatives monopolize the power to rule, then democratic rights lose meaning. Democracy cannot be inherently equal, just, or beneficial.

For it to be so, people must have the opportunity to build their capacity to make informed decisions and to demand a fair share of democracy’s benefits. Only then can we talk meaningfully about good governance, institutional development, and genuine leadership.

Do the concerning trends we observe extend beyond political parties to the executive, legislature, judiciary, and other independent constitutional bodies?

Every institution has its own mandate and purpose, and it is important to examine whether these institutions have been fulfilling the roles for which they were established—and whether they have been able to deliver the services expected of them.

The legislature, particularly Parliament, is meant to be central to democratic governance. Yet, in practice, legislative functions have become minimal and ineffective. Parliament has struggled to hold the machinery of the state accountable.

Instead, we often see only the surface-level theatrics of power struggles between ruling and opposition parties. The first signs of the breakdown in the legal foundations of good governance begin right here.

The executive, meanwhile, has increasingly tried to bypass the legislature, especially when it fails to secure its loyalty. There is a growing trend of relying on ordinances and executive decisions, circumventing the normal legislative process.

Members of Parliament—except for ministers—appear preoccupied with feelings of powerlessness, competing for influence rather than engaging in constructive legislative work.

As a result, the Parliament, which should demand accountability from the executive, has become largely symbolic. Reduced to subsistence-level functioning, this condition poses a serious threat to democracy and the rule of law.

State institutions, which should ensure transparency, legality, accountability, institutional competence, and service quality, have instead become tools for personal or partisan gain.

Rather than enacting laws impartially and in line with democratic objectives, legal frameworks are increasingly shaped—or exploited—for hidden, self-serving agendas.

A disturbing pattern has emerged: attempts to weaken oversight mechanisms; service delivery marked by uncertainty and favoritism; prioritization of opportunity management over genuine capacity building; and a dangerous culture of loyalty to party lines over equitable public service. In this context, public administration is losing both credibility and purpose.

Consequently, the state struggles to even appear like a functioning government. Though public administration should be a key pillar of good governance, it has become neither citizen-centric nor driven by principles of democratic accountability. Instead, it risks becoming a symbol of inefficiency and suffering.

The judiciary, too, is not immune to these trends. It faces difficult questions: How quickly and effectively are rights enforced? How accessible is justice for ordinary people? Is the public’s trust in judicial institutions increasing or eroding? Is the legal system easing or worsening the burdens people face—particularly the poor—when seeking justice?

Issues such as delays, high litigation costs, lack of reimbursement for wronged parties, and a general sense of judicial insecurity have remained unresolved.

The public’s awareness of their rights has not significantly improved, nor has accountability among institutions and officials been meaningfully strengthened. Often, actions appear to be taken only to pay lip service to governance values, not to realize them. Deviation and impunity have become normalized.

Ill-gotten wealth is now seen as success. Discipline is viewed as outdated. Though such trends may sound exaggerated, they are increasingly reflective of today’s reality.

As a result, large sections of the population—especially the youth—have sought opportunities abroad. The country’s own wealth and potential have failed to retain its future generation. It is now commonly said that the only thing left for the country to export is its people.

Our economy survives on remittances, while agriculture, industry, and service sectors are left neglected. The state shows no remorse. In fact, even in the labor migration process, it is the poor who are exploited the most.

How did we arrive at this point—where the country has become so unattractive to its own people? Is this not the most alarming trend for any nation? Can we continue down this path indefinitely? Can our national existence remain intact if these trends go unchallenged? These are the questions that keep me up at night.

The situation we face today calls for a serious and honest review of the relevance and justification of our past efforts, institutions, and systems. Despite experimenting with various constitutional arrangements—now reaching our seventh constitution—the implementation of these frameworks has yielded little to be proud of in terms of good governance, sustainable development, or meaningful prosperity.

There remains a persistent failure to connect governance with growth, and development with equity. Although good governance has been the stated goal of each constitutional framework, none has been able to chart a clear, practical, and coordinated roadmap toward achieving it. Why has this continued to happen? It is time we seek an answer.

These are not simple or one-dimensional questions. They touch upon the full spectrum of national life: economic development, the rule of law, institutional maturity, physical infrastructure, the adoption of good governance values, and—most importantly—the advancement of human development.

A nation’s progress is not achieved through isolated successes in these areas, but through their integration into a coherent whole. Civilization, prosperity, and public satisfaction emerge from the synergy between these components.

Unfortunately, our existing indicators are ill-equipped to measure whether these elements are working together in harmony—or whether we are even moving in the right direction.

No society, institution, or system plagued by widespread despair, administrative distortions, and institutional dysfunction—combined with an inferiority complex—can be expected to produce meaningful solutions.

Therefore, we must shift the question. Instead of only identifying the failures, we must also interrogate our own roles and responsibilities in perpetuating these conditions.

But the purpose of this review must go beyond observation. It must be diagnostic and solution-oriented. Conscious, active, and transformative efforts are urgently required.

Today, we face a bleak reality: we lack the economic resources and political environment needed to ensure good governance. Reliable and beneficial international support is scarce.

Public awareness and citizen capacity are limited. Our workplaces have not nurtured an environment conducive to integrity and service. Even a culture of law enforcement has failed to take root.

These challenges must be seen in relative, not absolute, terms. Despite all these limitations, we are still alive as a nation. These problems do not signify our total failure or inaction.

Rather, they signal the urgent need for more committed and informed efforts to address the conditions they reflect. Many nations have faced similar crises—some responded earlier, and with greater honesty and discipline. Perhaps we have lagged behind in those very qualities.

We now have no choice but to initiate new collective and regional efforts to resolve these issues. We cannot continue as we are. The present moment demands that we rise to it—not with despair, but with renewed energy and purpose. We must decide: will we remain stagnant and disheartened, or will we reimagine and redefine our national presence?

The ability to engage with problems—no matter how small or large, high-level or grassroots—is now our greatest need. Earlier, I outlined challenges at every level: constitutional implementation, governance mechanisms, and areas of development.

Upon deeper inspection, these problems are rooted in multiple causes. But among them, one stands out as fundamental: the lack of sustained institutional development. And beneath that lies the critical failure of leadership development.

Today, analyzing and adopting systems has become relatively easy. We can study, critique, and select models that appear efficient or modern. But it is essential to understand that no system exists in a vacuum.

The successful application of any system depends on the context in which it is introduced: the history, geography, economy, social structures, collective psychology, work culture, and the values of the people.

This sum total is what we call a society’s social context. And contexts differ—sometimes profoundly—from one country or community to another. What works in one place may be irrelevant or even harmful in another.

In an age of globalization, originality is difficult—but not impossible. What is essential is the capacity to select, adapt, and internalize policies and systems that align with our own capabilities, culture, and aspirations.

The judiciary, overburdened and under-resourced, struggles with delays and accessibility. Other constitutional bodies—established to provide checks and maintain democratic balance—are themselves mired in politicization, rendering them weak and ineffective.

In our case, from the very beginning of the constitution-making process, imitation prevailed over introspection. Aspirations were borrowed, and realities were overlooked.

Policies and institutions were often adopted impulsively—more as a gesture toward modernity or progressivism than as tools for meaningful transformation. Little attention was given to whether these ideas could actually work within our own context.

As we entered the phase of constitutional implementation, neither the rights enshrined in the constitution were effectively realized, nor was the capacity to exercise them adequately developed. It is tempting to assume that the enforcement of rights rests solely with laws or the judiciary. However, the deeper truth is that the effective realization of rights fundamentally depends on the people’s awareness of those rights, their ability to claim and enjoy them, and the existence of enabling conditions that translate legal rights into lived experiences.

For rights to be more than aspirational declarations, there must be development achievements that make those rights usable, and there must be a sensitive, competent, and accountable state apparatus.

Additionally, the judiciary must be capable of creatively and effectively mediating the relationship between the state and its citizens. Merely inscribing rights in the constitution—where they can be seen and heard, but not experienced—reduces them to symbolic gestures without substantive impact.

Ideally, the organs and mechanisms of the state should be both organically interconnected and functionally autonomous. They must work in coordination while preserving their respective roles.

In reality, however, these institutions have often either encroached upon one another’s domains or neglected their constitutional responsibilities. In the first case, autonomy is undermined; in the second, subordination results in dysfunction. In both scenarios, the institutions fail to achieve their intended purpose and lose their public legitimacy.

Today, the relationships between constitutional organs and their levels of efficiency are deeply unsatisfactory. Parliament remains largely unproductive. The executive is marked by instability and crisis management rather than stable governance.

The erosion of legal frameworks, the personalization of legislation for self-interest, and the formation of unprincipled political coalitions have contributed to an executive branch that often fails to represent clear and consistent public interests. Increasingly, it is unclear whose interests the executive truly serves.

The judiciary, overburdened and under-resourced, struggles with delays and accessibility. Other constitutional bodies—established to provide checks and maintain democratic balance—are themselves mired in politicization, rendering them weak and ineffective.

The rule of law—central to any framework of good governance—has been seriously compromised. We lack both the confidence that laws will be appropriately formulated and the assurance that they will be implemented equitably.

Legal compliance is inconsistent, and violations occur openly from the top to the grassroots level. Selective prosecution, politicized investigations, and biased sentencing practices erode the universality and fairness of the law.

Unequal forgiveness for some and undue harshness for others has undermined the principle of equality before the law. This is one of the most serious challenges facing our democracy today.

Public service delivery, too, suffers from systemic failure. While access to public goods and services should be universal, efficient, and accountable, the current system is plagued by discrimination, inefficiency, high costs, delays, complexity, and opacity.

Complaint-resolution mechanisms are often weak or inaccessible, pushing citizens into lengthy and complicated judicial processes for even minor grievances. This dysfunction persists at nearly every level of government and across most state institutions.

Wider economic and market distortions also reflect this failure of governance. The open market has become opaque and unreliable. Economic opportunities appear artificially constructed and unequally distributed.

This lack of transparency and predictability has affected everything—from market management to development outcomes to living standards.

At the heart of all this lies the critical need for institutional development—and, most importantly, for leadership development. Especially in Nepal’s context, the disconnect between the stated objectives of government bodies and their actual performance is stark. From the central government down to local public service providers, institutions have rarely succeeded in fulfilling their foundational mandates.

Had the key actors of the constitutional system performed their roles with integrity and vision, we would not be facing today’s widespread confusion, instability, and systemic dysfunction.

While the constitutional structure may formally define the duties, rights, and powers of each institution, in practice, these organs have failed to fulfill their responsibilities in a way that generates public trust and satisfaction.

Even laws critical for constitutional implementation—such as those governing the police, civil service, and federal structure—have not been enacted even a decade after the constitution’s promulgation. Federalism remains incomplete and immature.

There is no legal framework, institutional infrastructure, or accountability mechanisms in place to guarantee rights. As a result, the promise of the constitution remains largely unfulfilled.

From the perspectives of both the separation of powers and checks and balances, ad hocism appears to have become institutionalized. Politicization in appointments and the absence of a deep, unwavering sense of public duty among appointees have significantly weakened the system of checks and balances.

Governing by ordinance has become more convenient than legislating through proper parliamentary processes. Meanwhile, the sense of independence and dignity expected from constitutionally mandated commissions remains alarmingly absent.

Parliament has struggled to maintain its relevance; the executive is unable to secure essential legislation from the legislature; and the judiciary, under pressure from capacity constraints and rising public expectations, has not demonstrated the agility or effectiveness needed to address constitutional uncertainties. These systemic failures point to an alarming void in constitutional leadership.

Leadership is not an inborn trait; it is cultivated through practice, reflection, commitment, and moral clarity. A blend of knowledge, skill, loyalty, compassion, and strategic thinking makes leadership possible.

The erosion of legal frameworks, the personalization of legislation for self-interest, and the formation of unprincipled political coalitions have contributed to an executive branch that often fails to represent clear and consistent public interests. Increasingly, it is unclear whose interests the executive truly serves.

The practice of forming opportunistic coalitions for the sole purpose of power-sharing has fundamentally undermined the spirit of multi-party democracy and competitive governance.

Across sectors—education, health, employment, agriculture, trade, and productivity—imbalanced and unproductive trends are emerging, leaving little room for optimism.

The constitutional system has failed to deliver not only because of structural and procedural weaknesses but also due to institutional stagnation and lack of resources.

Questions are now being raised not just about past failures, but about the very capacity of the current system to generate meaningful outcomes, restore public trust, or inspire national enthusiasm.

Ironically, while political actors claim ownership of the constitution-making process, they have neither demonstrated accountability for its implementation nor accepted responsibility for its failures.

The Leadership Question

Political competition continues, but the absence of capable and responsible leadership is stark. There is a shortage of individuals who possess the vision, discipline, and integrity required to fulfill constitutional mandates.

The core issue today is the failure to cultivate the leadership necessary for constitutional institutions to function as intended.

Implementing the constitution is not the responsibility of any single party or individual—it is a shared duty across institutions. Yet, those entrusted with constitutional roles have largely failed to demonstrate the competence and accountability their positions require. Too often, assuming office has become a ritual, not a commitment to responsibility.

Regardless of whether someone reaches office through election or appointment, the leadership vacuum persists. Inaction and complacency at the top are no match for the complex and pressing problems we face.

Without a well-defined vision, a clear roadmap, and the ability to inspire participation and collaboration, no policy—however noble—can succeed.

Sustainable progress is achieved through cooperation, not coercive power. This is where our leadership consistently falters. Therefore, the question of how leadership develops is more critical than ever.

Contrary to common assumptions, leadership is not inherently produced by elections, nor is it excluded from being developed through appointments. Leadership is not simply about holding authority—true authority flows from demonstrated competence. Without the capacity to lead effectively, positional power becomes irrelevant.

Leadership should be capable of engaging in meaningful dialogue, fostering cooperation, and linking policies to measurable results. Without such preparedness, the state risks falling into a cycle where people are neither properly represented, nor served, nor held accountable.

Leadership also does not belong exclusively to those in power. Many individuals lead by example through service in education, civil society, justice, and advocacy—without holding formal authority.

Leadership is not an inborn trait; it is cultivated through practice, reflection, commitment, and moral clarity. A blend of knowledge, skill, loyalty, compassion, and strategic thinking makes leadership possible.

Yet, in our political culture, we continue to label all politicians as leaders, even when they have failed to lead. We retain ineffective figures out of habit, loyalty, or resignation—and therein lies a fundamental flaw.

The notion that leadership resides only in one person or a select few is misguided. The goals of a nation or an institution are achieved through the collective work of many branches and sectors.

Each unit, each role, carries responsibility. Decentralized, accountable leadership is not just a democratic ideal—it is a functional necessity.

Those who believe in democracy must resist the temptation to glorify a single, all-powerful figure. What we need is a plurality of leaders—capable individuals who can shoulder delegated responsibilities and deliver results across institutions and levels. An expanded, more inclusive understanding of leadership is the need of the hour.

These reflections apply across all organs of the state—the executive, legislature, judiciary, and other constitutional or public bodies. The state must begin to view itself as a unified yet interdependent system, where each part complements the other rather than operating in isolation or competition.

No institution can fulfill its mandate alone, nor should any be allowed to function without accountability. Leadership must be nurtured within this framework of mutuality, complementarity, and autonomy—anchored in constitutional purpose and national responsibility.

Even though every institution or constitutional body has a designated leader, it is worth asking: how many of them have demonstrated contributions that are institutionally meaningful and a source of pride?

The notion of meaningful tenure is vanishing. Rather than evaluating their impact, leaders often measure their time in office simply by the passage of time. Power and privilege have been overvalued, while accountability has been severely undervalued. A fundamental shift in this culture is urgently needed.

No matter how often we amend the constitution, revise laws and policies, restructure institutions, or allocate resources—if the governance system remains stagnant, if progress remains invisible, and if qualifications continue to be ignored, then all efforts are in vain.

Across both the bureaucracy and the political sphere, there is a persistent absence of the right combination of competence, integrity, and leadership.

So long as the assumption persists that leadership naturally emerges from elections, or that passing a civil service exam inherently produces capable administrators, leadership will remain more rhetorical than real.

While remittance has supported the economy, it is deeply problematic to normalize the notion that emigration is inevitable or desirable. A state dependent on its youth leaving the country must ask itself hard questions about the viability of its future.

This highlights the need for a deliberate, well-planned national program for leadership development—grounded in an honest recognition of this deficit.

The Need for Strategic Human Resource and Leadership Development

We must create conditions where institutions can achieve their objectives through a workforce equipped with a minimum foundational understanding of key national dynamics: geography, history, culture, law, economics, psychology, population trends, and international relations.

Leadership should be capable of engaging in meaningful dialogue, fostering cooperation, and linking policies to measurable results. Without such preparedness, the state risks falling into a cycle where people are neither properly represented, nor served, nor held accountable.

After reflecting on current weaknesses, it becomes clear: we need bold and visionary leadership—leaders who can steer the country toward new, realistic goals and away from repetitive excuses. A person who merely cites reasons for failure cannot be expected to bring about transformative change. Therefore, the search for transformative leadership is crucial across all areas of governance.

Today, governance suffers from a top-down control mentality. Instead of striving to build a system that is transparent, accountable, and citizen-centered, there is an inclination to centralize control.

This is compounded by the fragmentation and politicization of institutions, the incomplete and uncoordinated implementation of federalism, and growing public distrust at all levels. As a result, the ideal of good governance has been reduced to mere rhetoric.

Even routine issues, especially at the local level, are met with obstruction and confusion rather than solutions. The adoption of information technology, instead of easing service delivery, has added complexity—making services less accessible, not more.

Citizen grievances are often neglected, and complaint mechanisms are ineffective. A worrying symptom of poor governance is the rising disillusionment with systems meant to simplify public service.

It is therefore imperative to develop governance systems that promote a genuine culture of service, prioritize efficiency and ease, and measure performance based on how conveniently and equitably services are delivered. Innovation and reform must be embedded in institutional development to ensure this.

Good Governance as Self-Governance

At its core, good governance is self-governance. When citizens feel empowered to participate in governance and access public services fairly and comfortably, trust grows, and conflict diminishes.

Service delivery must be inclusive—ensuring equal access for all members of society, regardless of background. Unfortunately, that ideal remains distant. One clear symptom of weak governance is the erosion of trust in formal procedures and the growing belief that outcomes are only possible through informal or alternative means.

High unemployment, internal displacement, youth emigration, and the widening wealth gap reveal a deeper malaise: our governance system has failed to offer security, opportunity, or hope.

For many, the difficult process of seeking public services may itself be a driving force behind their decision to leave the country. That people no longer see the nation as livable—or believe that change is possible—is a dangerous trend. And yet, even amid these developments, there appears to be no strategic, coordinated development response from the state.

Development plans prepared by the National Planning Commission routinely excluded the judiciary. At times, the shortage of resources was so severe that courts could not issue written verdicts because there was no paper available.

While remittance has supported the economy, it is deeply problematic to normalize the notion that emigration is inevitable or desirable. A state dependent on its youth leaving the country must ask itself hard questions about the viability of its future.

Toward Institutional and Systemic Renewal

Good governance cannot be realized by a single agency operating in isolation at the central level. It requires coordination and active participation from all relevant institutions—nationally and locally.

To advance institutional development, we must undertake comprehensive human resource planning, set achievable and meaningful goals, create roadmaps for implementation, cultivate institutional solidarity, build operational capacity, and ensure reliable service delivery.

Institution-building is not a mechanical task. It requires aligned efforts from many people working toward a shared objective. Institutional mandates, no matter how noble, do not fulfill themselves automatically. They must be achieved through the deliberate design of appropriate processes, structures, environments, and capabilities.

Far too often, institutions are treated as complete once staff are appointed and budgets secured. But an institution only justifies its existence when it delivers reliable, timely, and fair services to its intended beneficiaries.

Therefore, institutional development that supports good governance must be driven by committed leadership—leadership that understands not only the mandate of the institution but also the people it serves.

Without synergy between leadership and institutional development, institutions cannot function as the backbone of democratic governance. To move forward, we must invest in both—and urgently.

Reflections on Judicial Reform: A Forty-Year Journey

Every institution carries its own story of growth, struggle, and transformation. Before concluding, I would like to share a few reflections from my forty years of experience in the judiciary—a journey marked by deep institutional challenges, persistent effort, and gradual but meaningful reform.

The judiciary, despite being constitutionally entrusted with a critical role, long operated as an outdated and under-resourced institution. It was often overlooked in national priorities and functioned without proper infrastructure, housing, transportation, computers, training materials, books, newspapers, or even basic office supplies.

Although expected to serve as the guardian of constitutional rights, the final arbiter between citizens and the state, and the regulator of institutional balance, the judiciary lacked the fundamental tools to carry out its mandate effectively.

These responsibilities, though clearly defined in the constitution, could not be translated into action due to a lack of investment, capacity-building, proper procedures, and institutional preparedness.

A sustainable and effective judiciary requires both structural commitment and financial investment, neither of which can be delayed if we expect the justice system to meet public expectations and uphold the rule of law.

Development plans prepared by the National Planning Commission routinely excluded the judiciary. At times, the shortage of resources was so severe that courts could not issue written verdicts because there was no paper available.

In some cases, parties were required to physically write down their statements. The courts struggled under a level of physical and procedural underdevelopment that was difficult to reconcile with the standards of the modern world.

Public awareness of the judiciary’s role remained limited, and state investment in the judiciary was often perceived negatively—as if supporting the justice system meant encouraging disputes.

This perception hindered serious discussion about reform. Against this backdrop, the need to develop a comprehensive strategy for judicial reform became increasingly urgent.

When the idea of reform was first introduced, it was clear that making a plan would not be enough—implementation would require commitment and ownership.

The notion of strategic planning was unfamiliar to many in the legal field and was initially met with resistance. Even within judicial circles, the relevance of strategy was questioned. Nevertheless, a strategic plan was formulated and set in motion.

Despite the availability of several reports outlining problems within the judiciary, implementation was weak. Strategic plans prepared by the Supreme Court and sent to lower courts failed to generate much engagement or institutional ownership. As a result, the initial phase of reform did not produce the desired outcomes.

When the second plan was introduced, the approach shifted. Each court was encouraged to prepare its own annual plan within the framework of a five-year strategy.

This model proved more effective in fostering ownership and accountability. With clearer institutional objectives, courts began identifying their values, timelines, responsible officers, and implementation procedures.

Regular monitoring and evaluation were introduced, and this new structure brought momentum to reform efforts.

The reform strategy focused on reducing case delays, improving case management, streamlining work procedures, curbing irregularities, ensuring effective implementation of judicial decisions, strengthening relationships with stakeholders, and improving the management of limited resources.

Over time, the judiciary progressed through successive plans and is now operating under its fifth strategic plan. However, a persistent obstacle remains: inadequate funding.

The government has repeatedly approved only a small portion of the budget proposed in the strategic plan, which continues to hinder full implementation.

It is important to recognize that merely declaring institutional objectives and setting up administrative structures does not guarantee that an organization will function effectively or achieve its intended goals.

To address this issue and promote more equitable resource allocation, a study tour was organized for officials from the Ministry of Finance and the Planning Commission.

The tour aimed to provide comparative insights into how developed countries finance their judiciary and justice sectors. The objective was to encourage a broader understanding that the judiciary, as a co-equal constitutional institution, must be allocated a budget that reflects its responsibilities—not a token amount at the discretion of the executive.

Although this initiative contributed to some changes in the way court budgets were discussed and demanded, the actual allocations remain far from adequate.

A sustainable and effective judiciary requires both structural commitment and financial investment, neither of which can be delayed if we expect the justice system to meet public expectations and uphold the rule of law.

However, as part of the planned reform initiatives, the judiciary has seen notable improvements in its physical environment and infrastructure in recent years.

The integration and use of information technology have become more widespread, contributing to operational efficiency. There has been a marked increase in the rate of case resolution, and efforts to enhance capacity through institutional mechanisms within the judiciary have made some progress.

Compared to the past, the judiciary has now entered a more advanced phase of institutional modernization. While judicial consumer satisfaction remains a relative and evolving measure, it is clear that continued, sustained effort is required to maintain and improve public trust.

It is important to recognize that merely declaring institutional objectives and setting up administrative structures does not guarantee that an organization will function effectively or achieve its intended goals.

An organization must be empowered and capacitated to deliver services effectively. This requires strategic preparation and deliberate efforts to enhance its capability.

These transformations do not occur on their own. They demand a leadership force with the vision, dedication, and capacity to guide, manage, and coordinate change.

Only through such visionary leadership—alongside strengthened institutional capacity and effective service delivery—can the ideals of good governance truly be realized.

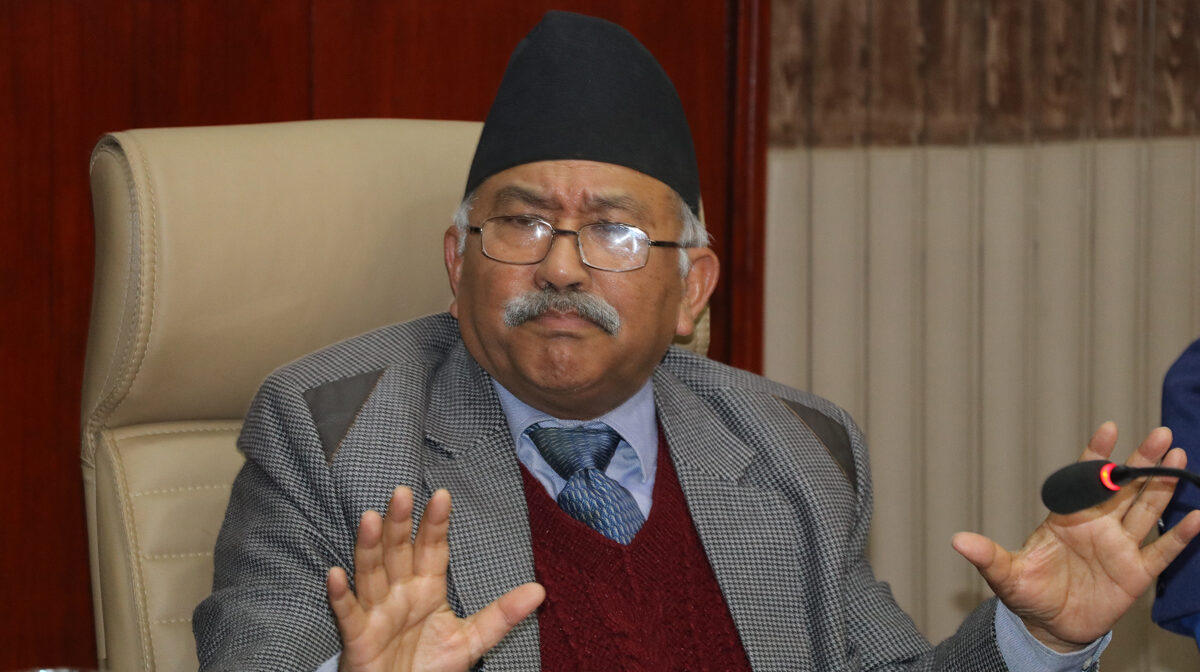

(Excerpt from the speech delivered by former Chief Justice Shrestha, recipient of the Hem Bahadur Malla Award-2080, at the award distribution ceremony held at Soaltee Hotel on Thursday.)

Comment