China’s rise is one of the most significant challenges to US influence in Asia and the world. Scholars have debated over the nature and effects of geopolitical rivalry between China and the United States, often predicting tumultuous relations between the two nations by drawing inferences from past hegemonic competition or current incompatible political systems.

Such alarming forecasts appear more realistic under the administration of Donald Trump. Along with the ongoing trade war with China, the Trump administration in its 2017 National Security Strategy document unmistakably called China a “strategic competitor.”

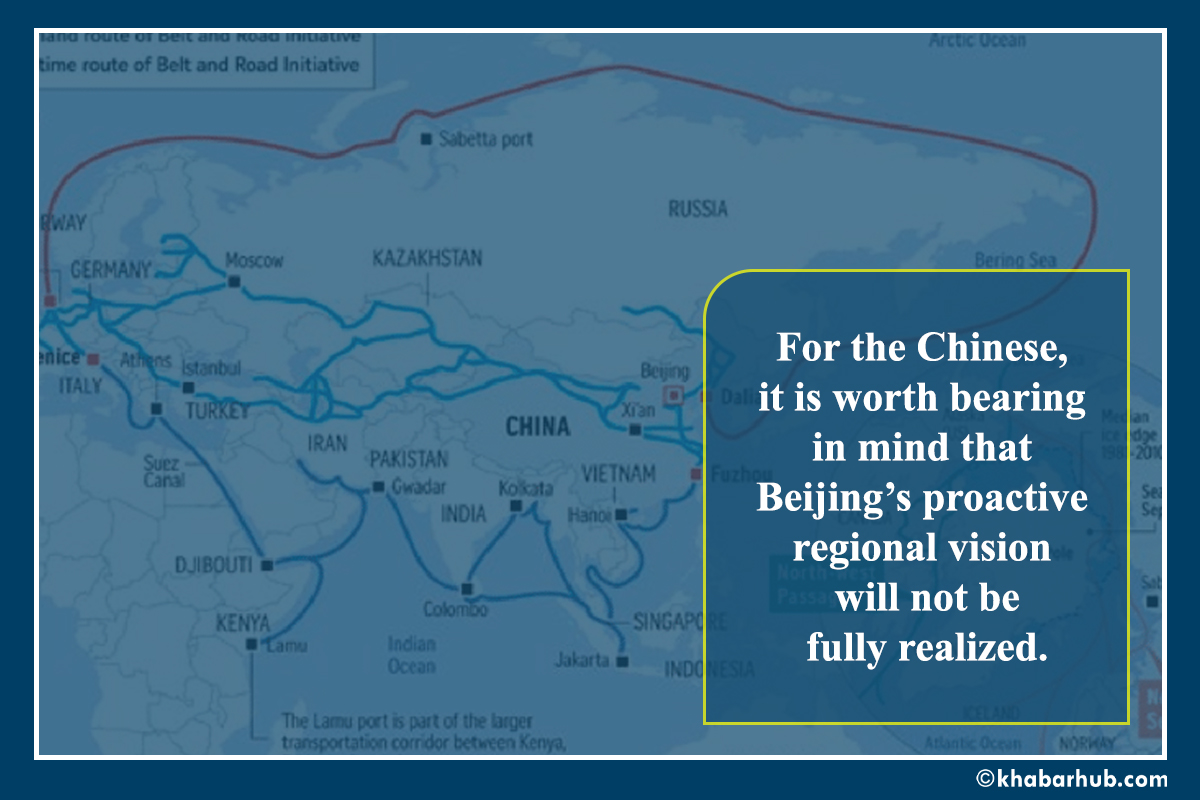

US National Security Advisor John Bolton depicted China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a primary means for Beijing to seek “global dominance.”

The Trump administration in turn unveiled the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy to counter China’s global strategy.

With the BRI, the Xi Jinping government initially focused on various infrastructure deals with nations along the Eurasian region, but in recent years, Beijing has increasingly turned toward the geo-strategic goals of securing long-term port access and enhancing strategic ties with key regional states.

Highlighting open trade and connectivity, the Trump administration has stressed the role of India and officially renamed the US Pacific Command to the US Indo-Pacific Command.

What will be the likely effects of the dueling hegemonic strategies in Asia? In addressing this question, this paper seeks to investigate the perceptions and motivations of Japan, South Korea, and India with respect to the BRI and the FOIP.

Despite their strategic ties with the United States, each of these countries have responded in various ways to the two hegemonic visions.

Specifically, South Korea, a US military ally, has not joined the FOIP despite Trump’s invitation, instead seeking to work with China on the expansion of the BRI into the Korean peninsula.

By comparing the domestic debate about the BRI and the FOIP in the three Asian nations, this paper explores the ways in which each nation comes to grips with the dueling hegemonic strategies.

The Narendra Modi government in India welcomes the FOIP but calls for greater inclusivity aimed at engaging the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China.

The Abe Shinzo government in Japan is more enthusiastic about the FOIP but reaches out to Beijing over the BRI as well.

These varied responses to the BRI and the FOIP suggest that balancing and bandwagoning are insufficient to capture the Asian realities.

While aligning themselves with Washington or China over some regional issues, the Asian nations remain hesitant to fully embrace the competing hegemonic visions.

In this paper, I contend that a key driver behind these strategic calculations is the pursuit of greater regional autonomy in a changing regional order.

Instead of following the footsteps of the two superpowers, Japan, South Korea, and India seek to carve out their own regional space and draw on the two hegemonic initiatives for their own specific foreign policy goals.

By comparing the domestic debate about the BRI and the FOIP in the three Asian nations, this paper explores the ways in which each nation comes to grips with the dueling hegemonic strategies.

As long as politicians in Tokyo, Seoul, and New Delhi stake out their regional positions on the basis of foreign policy autonomy, both the US push for an anti-China coalition and China’s drive to alter the regional order to Beijing’s liking are less likely to succeed.

An analysis of the regional responses to the BRI and the FOIP will also help us better conceptualize the evolving regional order in East Asia.

In the following section, this paper critically examines various accounts of state response to rising powers. It then advances an argument based on foreign policy autonomy considerations.

The next section briefly highlights the key features of the BRI and the FOIP. The subsequent three sections in turn delve into the Japanese, South Korean, and Indian domestic debates about the dueling strategies. The final section concludes with a brief summary of the findings and a discussion of theoretical and policy implications.

Explaining Variation in Regional Responses to the BRI and the FOIP

There are various scholarly accounts of state behavior in the face of emerging powers. A realist explanation centers on balancing behavior.

From this perspective, regional countries tend to be “more sensitive to threats from other regional powers” due to geographical proximity.

Specifically, from this vantage point, states confronting a rising power in an anarchic world are likely to turn to either internal balancing (i.e., increasing their own military capability) or external balancing (i.e., working with allied nations).

As for South Korea, in the face of North Korea’s provocations, the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye governments strengthened their alliance ties with the United States.

For instance, John Mearsheimer argues that in light of a rising China, its regional neighbors, such as “India, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Russia, and Vietnam, will join with the United States to contain Chinese power.”

In the East Asian context, this balancing perspective expects that Japan and South Korea would either revamp their own defense posture or strengthen their alliance ties with the United States.

For instance, according to Richard Samuels, the rise of China provoked “Japanese diplomacy toward balancing partnerships” with other regional countries.

Along with the launching of the National Security Council and the revision of the National Defense Program Guidelines, the Abe Shinzo government’s push for a “dynamic defense force” is viewed mainly as an effort to balance and “reinforce deterrence toward China.”

As for South Korea, in the face of North Korea’s provocations, the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye governments strengthened their alliance ties with the United States.

Many have similarly attributed India’s post–Cold War “Look East” policy to New Delhi’s effort to balance against China in the South Asian and Asia–Pacific regions.

Other scholars, however, expect that Asian states would either bandwagon with or at least accommodate China.

Pointing to limited balancing against China, David Kang argues that both material interests in the present and shared history and interaction in the past gravitate East Asian states toward accommodating China.

Similarly, Bjorn Jerden and Linus Hagstrom assert that throughout the Cold War period and beyond, Japan has been accommodating China by “facilitating the successful implementation of China’s grand strategy, and hence by respecting China’s core interests and acting accordingly.”

The bandwagon account is particularly useful given its due consideration of the perspectives of local actors. It also illuminates the limited levels of balancing dynamics in the region.

What is puzzling, however, is that neither balancing nor bandwagoning adequately captures the ways in which these three Asian nations have responded to the BRI.

While they are among the world’s most sophisticated armed forces, Japan’s defense budget of less than one percent of its GDP and South Korea’s peninsula-focused defense posture hardly suggest internal balancing against China.

India’s defense budget for 2019 is USD 49.68 billion, with a marginal increase that is far short of its modernization plan.

As shown in the empirical sections below, a regional record of external balancing in the form of a strengthened alliance relationship with the United States is also mixed at best.

As for bandwagoning as well, there is wide variation in the three countries’ approaches to the BRI (e.g., active, conditional, or no participation).

What the existing accounts miss is that systemic factors, such as changes in the power distribution among states, are filtered through the domestic political prism.

Hedging, where states engage potential enemies while keeping the option of balancing with allies, is another possibility for smaller states in East Asia.

For instance, a policy proposal by the Tokyo Foundation recommended a three-tiered policy of “integration, balancing, and deterrence” toward China.

Similarly, one scholar describes Modi’s policy toward China as “a more consolidated hedging component combined with a more robust engagement policy towards China.”

While useful in understanding the regional nations’ cautious approach toward Beijing, this account remains ambivalent about permissive conditions for balancing and engagement.

Lost in the wide spectrum of scholarly expectations is the attention to the domestic process of interpreting and coping with the challenge of a rising power.

What the existing accounts miss is that systemic factors, such as changes in the power distribution among states, are filtered through the domestic political prism.

In this regard, Amitav Acharya questions the mainstream international relations discussions of Asian security, which “treat China as if it is the only country in the region and focus more on the U.S.-China relationship than on East Asia itself.”

Instead, he argues that “it is these interactions [between the United States and China on the one hand and other regional states on the other] that are going to have the most impact on stability.”

Building on this insight, this paper seeks to demonstrate how local political dynamics in Tokyo, Seoul, and New Delhi intersect with the broader American and Chinese grand strategies.

In unpacking the domestic political process of interpreting the challenges and opportunities associated with China’s rise, I contend that we need to pay greater attention to considerations of foreign policy autonomy.

A rising power and the subsequent change in the regional power balance may affect the nature of strategic relationships among states.

Under this strategically fluid circumstance, political leaders weigh the potential values of gaining material benefits from great powers against the possible costs of ceding too much foreign policy independence to them.

It is worth noting here that hedging strategy is often pursued because official alliance ties may risk “losing their independence and inviting uncalled-for interference.”

Bandwagoning with China is also politically untenable for Japanese and South Korean leaders eager to secure greater regional autonomy. In fact, Japanese and South Korean leaders “have rarely assumed or accepted unquestioned American or Chinese leadership roles” in the region.

With its tradition of nonalignment and independence in foreign policy, India has also maintained strategic straddling between balancing and bandwagoning vis-à-vis China.

Overall, far from joining the US-led balancing coalition or bandwagoning with China, Japan, South Korea, and India focus on different aspects of the BRI and the FOIP to enhance their regional autonomy and promote their foreign policy goals.

Specifically, for domestic political actors who seek autonomy from the United States, China’s BRI could serve as an opportunity to reassert their nation’s independent regional strategy and benefit specific national interests, such as South Korea’s Northern Policy and inter-Korean relations and Japan’s infrastructure export program.

On the other hand, other domestic actors may fear China’s potential to undercut their regional autonomy in the future, pushing for their nations’ participation in the US-led FOIP.

However, the BRI is not merely a series of infrastructure projects with smaller developing nations but rather a grand strategy that serves “China’s vision for itself as the uncontested leading power in the region.”

It is the nature of the domestic contestation on regional autonomy that shapes variation in regional responses to the BRI and the FOIP.

In what follows, this paper will first examine the Chinese and US grand strategies in turn. It will then delve into the domestic debate on the two hegemonic visions in Japan, South Korea, and India.

Contending Visions: The Key Features of the BRI and the FOIP

Officially entitled “the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road,” the BRI (or yidai yilu) was unveiled in 2013 after Pres. Xi Jinping’s speeches in Astana, Kazakhstan, and Jakarta, Indonesia.

Widely viewed as Xi’s “signature project,” the BRI represents China’s long-term master plan, which “seeks to integrate Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa into a Sinocentric network through the construction of land- and sea-based infrastructure.”

According to a director of the Central Party School’s Institute of International Studies, the BRI’s main goals include “promoting better-balanced domestic development, opening up China’s inland provinces to the outside world, expanding export markets for Chinese goods, and increasing available channels for energy imports.”

However, the BRI is not merely a series of infrastructure projects with smaller developing nations but rather a grand strategy that serves “China’s vision for itself as the uncontested leading power in the region.”

For its part, the Chinese government stresses that the BRI is “in line with the purposes and principles of the UN Charter,” such as respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity and cooperation.

With more than 3,000 individual projects, the BRI has also been incorporated into the Chinese Communist Party’s Charter during the 19th Party Congress in October 2017.

Despite its promises and the Xi government’s efforts to highlight mutual benefits, since 2017 many have criticized the BRI for its lack of transparency and various risks for participating nations.

For instance, the transfer of control of the port in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, to China for 99 years “sparked worldwide alarm about Beijing’s strategic intentions, along with allegations that China was setting a ‘debt trap’ for smaller countries,” while Malaysian prime minister Mahathir bin Mohamad depicted his nation’s railway projects with China as “unequal” and a “new version of colonialism.”

As questions began to mount over China’s underlying motivations behind the BRI, the Trump administration launched the FOIP strategy in 2017.

The term, the Indo-Pacific, was first incorporated into the US security discourse during the first term of the Obama presidency by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell, with the main focus on the “Quad” grouping of the four “like-minded” democracies, namely Australia, Japan, India, and the United States.

Compared to the Obama presidency, the Trump administration has taken “a more combative approach, formally designating China a ‘strategic competitor.’”

Building on Japanese prime minister Abe’s previous push for greater regional cooperation in the Indian and Pacific oceans, President Trump, during his trip to Vietnam in November 2017, stressed the importance of a “free and open” Indo-Pacific, which was incorporated into the US National Security Strategy document.

According to the US State Department, the Trump administration has several key objectives for the FOIP.

By nature, these are both economic, “to advance fair and reciprocal trade, promote economic and commercial engagement that adheres to high standards and respects local sovereignty and autonomy, and mobilize private sector investment into the Indo-Pacific,” and diplomatic, ”partnership on energy, infrastructure, and digital economy” with allies such as Japan.

However, Chinese analysts maintain that the FOIP is an updated version of Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” policy aimed mainly at reformulating America’s “alliances and partnerships to respond to China’s rise.”

From the strategic and military standpoint, the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report issued in 2019 by the US Department of Defense calls for greater partnerships with existing allies and new partners to establish “a networked regional security architecture.”

While emphasizing “strong alliances and partnerships,” the Trump administration also insists on “sharing responsibilities and burdens.”

Another key feature in the Pentagon report is characterization of China as a “revisionist power.”

In an attempt to counter China, the FOIP promotes good governance in the Indo-Pacific region by encouraging “transparency, openness, rule of law, and the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms” and “ensuring a peaceful and secure regional order.”

However, Chinese analysts maintain that the FOIP is an updated version of Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” policy aimed mainly at reformulating America’s “alliances and partnerships to respond to China’s rise.”

According to a Chinese analysis, unlike the Obama administration’s efforts not to brand its Asia pivot strategy as targeting Beijing, the Trump administration tends to predict “an all-round zero-sum strategic competition” with China and seeks to balance China with “a strong US-anchored coalition that keeps tight grips on US allies such as Japan and Australia and brings ASEAN and India into its orbit.”

The next section investigates the three case study Asian nations’ reactions to the evolving hegemonic competition.

Varied Responses to the BRI and the FOIP

Japan

Historically, Tokyo’s diplomatic approach has been focused on Japan’s regional autonomy, rather than outright military balancing.

Japan has sought “as much autonomy in its China policy as is compatible with maintaining the cohesion of its alliance with Washington,” and since the early years of the Cold War, political leaders have viewed “Japan’s interests vis-à-vis China as distinct from U.S. interests and sought to pursue an independent China policy.”

As such, irrespective of structural changes in the region, various Japanese policy makers across the ideological spectrum have called for an equidistance approach toward China and the United States.

The pursuit of regional autonomy resurged during the rule of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ).

Even before coming to power, the DPJ’s search of autonomy was evidenced in its 1996 party manifesto, which called for reducing Japan’s “excessive dependence on the U.S.,” while improving relations with countries in the region.

After the election victory in 2009, Hatoyama Yukio, the DPJ’s first prime minister, unveiled the East Asian Community initiative.

Stressing the notion of yu-ai (or fraternal love) among regional countries, Hatoyama made it clear that Japan’s cooperation with China and South Korea became “an extremely indispensable factor” in realizing the regional initiative.

Contrary to the expectation from the balancing perspective, Hatoyama, at his meeting with Chinese president Hu Jintao, proposed “an Asian EU.”

In his efforts to gain greater foreign policy autonomy, Hatoyama also attempted to revisit the 2006 US-Japan agreement to relocate the US bases in Okinawa, worsening the alliance relations.

Japanese analysts characterized the DPJ’s move as efforts “to distance Japan’s foreign relations from the ‘domineering’ United States and to strike a better balance between Japan’s relations with the United States and with the rest of East Asia.”

Hatoyama’s vision was well received in the region. In the midst of these warming circumstances, Japanese officials agreed with their Chinese and South Korean counterparts to “begin joint research by academic, government and private-sector representatives on the possibility of forging a trilateral free-trade agreement.”

The Hatoyama government, however, did not last long, as he resigned over a political scandal and his failure to realize a campaign pledge on moving US bases from Okinawa.

His successors, Kan Naoto and Noda Yoshihiko, similarly ended their terms early amid criticisms over the government’s handling of Japan’s Triple Disasters in 2011: the earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

The three-year DPJ rule ended with the 2012 election victory of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) led by Abe Shinzo. At first blush, Abe’s foreign policy stance appeared to be balancing against China.

For instance, Abe was focused particularly on cooperation with Southeast Asian nations, visiting seven of the ASEAN countries, many of them claimants in territorial disputes with China, and seeking to “contain China’s increasing maritime advances in the region.”

It was under these improving bilateral circumstances that Abe visited Beijing in October 2017—the first official visit by a Japanese prime minister in seven years. During the visit, Abe conveyed Japan’s “readiness to actively participate in the BRI.”

In a sign of the continued salience of regional autonomy, however, Abe framed the diplomatic moves not as a direct balancing mechanism against China but as bold regional leadership.

Abe thus claimed that he “succeeded in changing the general mood and atmosphere that was prevalent in Japan” by engaging in proactive shuttle diplomacy with various Southeast Asian nations.

However, the Abe government’s proactive regional approach went beyond Southeast Asia. In May 2017, Japan dispatched a delegation to the first Belt and Road Forum in Beijing.

During his meeting with Xi at the 2017 G20 summit, Abe expressed “Japan’s interest in collaborating with China in implementing the BRI.”

It was under these improving bilateral circumstances that Abe visited Beijing in October 2017—the first official visit by a Japanese prime minister in seven years. During the visit, Abe conveyed Japan’s “readiness to actively participate in the BRI.”

In addition, Abe reportedly proposed to start a “development cooperation dialogue” for joint infrastructure projects, some of which will be funded by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and the China Development Bank.

In May 2018, Japan and China also agreed to create a “public-private sector committee” for joint infrastructure projects in third countries.

Japan’s participation in the BRI, however, is based not solely on economic incentives but also on larger political considerations.

Given regional concerns about US commitment in the Trump era, Japan’s limited role in the negotiations with North Korea, and tense bilateral ties with South Korea over the history issue, working closely with China over the BRI has the potential to open up diplomatic space and enhance Tokyo’s regional autonomy.

Moreover, some of key political and business elites, especially politicians from the Komeito party, the LDP’s coalition partner, have supported Japan’s collaboration with the BRI.

It is with these domestic and regional political considerations that Abe told Chinese prime minister Li Keqiang that “[s]witching from competition to collaboration, I want to lift Japan-China relations to a new era. . . . Japan and China are neighbors and partners. We will not become a threat of each other.”

Beyond the government, a group of Japanese intellectuals, journalists and business leaders established in 2017 the Belt and Road Initiative Japan Research Center (BRIJC) with former Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo joining as the “supreme advisor” of the center.

It is important to note, however, that Japan’s charm offensive toward China is far from a bandwagoning exercise. Instead of playing second fiddle to China’s BRI, Japan highlights the importance of seeking “quality growth” and “quality infrastructure” with developing countries.

Similarly, the Abe government launched the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure and worked closely with the United States and Australia over the Indo-Pacific Fund.

More broadly, Abe has been careful to maintain a balancing act between the BRI and the FOIP. In fact, it was Abe who during his first term as prime minster in 2007 stressed the Indo-Pacific as a regional focus and called for Japan’s greater role in maintaining “peace, stability, and freedom of navigation” in the Indian and Pacific ocean.

When he returned to power in 2012, Abe resumed his push for proactive diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific by joining the FOIP.

The Northern Policy contributed to South Korea’s diplomatic normalization with Russia in 1990 and with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1992.

However, instead of being a passive follower, the Abe government promotes its own FOIP agenda.

For instance, the Japanese Foreign Ministry pledges that Japan will “enhance ‘connectivity’ between Asia and Africa through a free and open Indo-Pacific to promote the stability and prosperity of the regions as a whole.”

Similarly, the Abe government announced Japan’s new overseas assistance strategy for its FOIP with the aim of substantially expanding “Japan’s diplomatic playground beyond Southeast Asia to a wider area that includes the Indian subcontinent.”

Although Japan has welcomed the FOIP and worked with the Trump administration, Tokyo has not always followed the US moves, reflecting Japan’s emphasis on regional autonomy.

In contrast to the US focus on the military dimension, the Abe government’s official rhetoric about the FOIP has recently changed from a “strategy” to a “vision.”

After Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Abe government also “jumped right in the power vacuum in order to lead the trade deal without the US.”

Japanese leadership was critical in bringing the remaining 11 members to sign off on the deal in March 2018. Abe’s effort to revive the TPP is another example of Japan’s constant pursuit of greater regional autonomy in Asia.

South Korea

The partition of Korea since 1945 has essentially meant South Korea’s disconnection from the Eurasian continent, turning South Korea into a de facto island nation.

As such, the BRI provides South Korea with a unique opportunity to “reconnect with the rest of Asia to escape from [its] isolation.”

The first serious effort to expand South Korea’s diplomatic space and regional autonomy came in the late 1980s.

President Roh Tae-woo initiated “Nordpolitik,” or a Northern Policy, aimed at transforming South Korea’s “relations with northern socialist countries and North Korea” with the aim of “a greater diversification of South Korea’s trading partners” and promoting a peaceful security environment around the Korean peninsula.

The Northern Policy contributed to South Korea’s diplomatic normalization with Russia in 1990 and with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1992.

In contrast to his predecessor, Chun Doo-hwan, who came to power through a military coup and thus had no choice but to zero in on strategic ties with Washington to overcome his lack of legitimacy, Roh was relatively free from the political need to highlight alliance relations with the United States.

In seeking diplomatic rapprochement with the Soviet Union and the PRC, Roh “wished to shed Seoul’s role as Washington’s loyal subordinate.”

However, it was the Roh Moo-hyun government that drastically improved South Korea’s relations with China. For instance, in March 2005 when US policy makers warned of China’s military modernization and called on South Korea to take “a more regional view of security and stability,” President Roh made it clear that South Korea would “not be embroiled in any conflict in Northeast Asia against [its] will.”

In the same month, Roh unveiled South Korea’s “balancer role” (gyunhyungja-ron) “not only on the Korean peninsula, but throughout Northeast Asia.”

Contrary to expectations from the balancing perspective, however, Roh stressed the importance of working closely with China. A key factor behind the strategic shift was “the desire to reduce dependence, both economic and strategic, on the United States.”

However, the conservative president Park Geun-hye was keen not to choose between Washington and Beijing, seeking to improve both the alliance ties with the United States and the strategic partnership with China.

Park’s signature project was her “Eurasia Initiative.” In fact, the announcement of Park’s initiative coincided with the unveiling of the BRI in 2013, and the South Korean initiative was similarly aimed at “economic cooperation in Eurasia through infrastructure projects, such as the trans-Korean railway.”

From the Eurasia Initiative’s inception, President Park observed that the South Korean initiative could be linked to China’s new Silk Road project, thus encompassing Northeast and Central Asia, Africa, and Europe and benefiting both Seoul and Beijing.

South Korea’s serious foray into the BRI, however, began in 2017 as the newly installed Moon Jae-in government stressed the economic link between the BRI and the Korean peninsula.

During his 2017 visit to China, President Moon stated that he and President Xi “agreed to actively look for ways of actual cooperation between China’s One Belt, One Road initiative with South Korea’s New North and New South policies.”

This is why Beijing has recently expanded the BRI into Northeast Asia, which could be connected to Russia, Mongolia, and the Korean peninsula.

Highlighting the importance of connectivity in Asia, Moon remarked, “If the connection between an inter-Korean railroad and the Trans-Siberian Railway that South Korea is actively pursuing meets China’s trans China, Mongolia and Russia economic corridor, the rail, air and sea routes of Eurasia will reach all corners of the region.”

Connecting to the BRI offers the additional benefit of reducing tensions between the two Koreas and promoting South Korea’s economy through land-based shipping and energy pipelines, thus replacing the far more expensive liquified natural gas.

Collaboration with South Korea has several benefits for China as well. For instance, a Chinese analyst points to the potential for stimulating economic growth in China’s three northeastern provinces and for incentivizing North Korea to adopt economic reform, “thereby creating a peaceful environment conducive for the BRI’s successful implementation.”

This is why Beijing has recently expanded the BRI into Northeast Asia, which could be connected to Russia, Mongolia, and the Korean peninsula.

In contrast to South Korea’s enthusiasm about the BRI, Seoul’s approach to the FOIP has been lukewarm at best. During his visit to South Korea in November 2017, President Trump encouraged South Korea to “participate in the ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) strategy, of which the ROK-U.S. alliance could be an integral part.”

Although South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs maintained that the FOIP “was consistent with South Korea’s diplomatic strategy to diversify foreign relations,” Moon’s chief economic advisor “flatly rejected the idea, claiming that the FOIP is a Japanese initiative to link Japan with the United States, Australia, and India.”

Instead, the Moon government has been seeking to increase its regional autonomy by reaching out to Eurasia, Southeast Asia, and India. A key focus has been its new “Southern Policy—an effort to increase economic and cultural cooperation with ASEAN, and economic and security cooperation with India.”

Instead of “simply following Washington’s lead,” Seoul appears intent on seeking “ad-hoc diplomatic support for non-controversial security initiatives,” specifically “participation in economic projects that suit Seoul’s needs, support for truly multilateral initiatives and prevention of any perceived antagonism towards China.”

At the same time, despite growing cooperation with China, Seoul is not bandwagoning with Beijing.

South Korea’s reliance on trade with China also means a growing sense of dependency and the potential for greater vulnerability in the future.

South Korea’s anxiety about its dependence on China materialized in 2016 when the Chinese government, upset about South Korea’s decision to deploy the US-designed theater missile defense system, penalized South Korean companies operating in China and limited the number of Chinese tourists to South Korea.

Another key constraint in working with China is the uncertain future role of North Korea in any of the regional initiatives.

This is why the Moon government has been eager to take a lead role in the nuclear negotiation with Pyongyang. From a South Korean standpoint, the success of the negotiation process would not only denuclearize the Korean peninsula but also expand Seoul’s diplomatic space and improve regional autonomy substantially.

India

Despite the shared experiences of starting their own civilizations and suffering from colonial invasion, India and China maintained a rocky relationship throughout the Cold War period, especially after the 1962 border war in which India suffered a humiliating defeat.

India’s tradition of nonalignment policy also affected its relations with China. Rooted in India’s independence movement, the nonalignment strategy kept India away from both the Western alliance and the communist bloc.

India’s cautious stance on China is reflected in its approach to the BRI. While not rejecting the initiative altogether, unlike Japan and South Korea, India has expressed concerns about China’s motivations behind the BRI.

Even after the US-China rapprochement in 1972, India’s ties to the Soviet Union hindered Sino-Indian relations.

However, after the Cold War, bilateral relations have turned into “a partnership of friendly cooperation and competition.”

As India’s economic growth accelerated, relations with China have gathered steam as well. As of 2018, China is one of India’s top five export partners and top import partner.

In addition, India has worked with China as members of BRICS, the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

In 2017, India also joined as a member of the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Given India’s desire to regain its great power status, these multilateral groupings could contribute to “greater parity, recognition and influence” for both India and China.

Despite New Delhi’s growing ties with Beijing, India’s strategic ambivalence toward China continues with the Narendra Modi government.

India’s cautious stance on China is reflected in its approach to the BRI. While not rejecting the initiative altogether, unlike Japan and South Korea, India has expressed concerns about China’s motivations behind the BRI.

In fact, India was “the first country to come out against the opaque BRI,” refusing to send delegates to the first BRI summit in May 2017.

Brahma Chellaney, a prominent Indian commentator, calls New Delhi’s position a “brave, principled stand against BRI,” as China’s project is perceived as “a non-transparent, neocolonial enterprise aimed at ensnaring smaller, cash-strapped states in a debt trap to help advance China’s geopolitical agenda.”

A statement from India’s Ministry of External Affairs raised the following concerns about the BRI: “[W]e are of firm belief that connectivity initiatives must be based on universally recognized international norms, good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency and equality.

Connectivity initiatives must follow principles of financial responsibility to avoid projects that would create unsustainable debt burden for communities; . . . Connectivity projects must be pursued in a manner that respects sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

Beyond its general concerns about the BRI’s overall direction and lack of transparency, New Delhi has specific concerns about the BRI’s impact on India’s security and regional interests, including “an entrenched China–Pakistan alliance that may subsume Indian influence in South Asia; mounting maritime, trade and naval competition in the Indian Ocean region; engrained border disputes.”

Among them, India is particularly worried about the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) over issues of sovereignty and territorial dispute in Kashmir.

Along with the CPEC, New Delhi has misgivings about “various points on the ‘Road,’ notably Gwadar port in Pakistan, and the Hambantota and Colombo ports in Sri Lanka.”

Among these concerns, the port in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, is “a glaring example of such unsustainable loans, which ultimately are allowing China to gain significant economic and strategic advantages in the Indian Ocean region.”

More broadly, as the Modi government seeks to enhance its regional autonomy and influence by reaching out to countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia, the BRI’s overlapping linkages to these regions alarm New Delhi.

As one analyst observes, the Modi government is “uneasy about Chinese designs for the region and how this challenges India’s own ‘neighborhood first’ approach.”

Specifically, the BRI is seen as a challenge to Modi’s regional initiatives such as the “Act East” policy. Under this policy, India has made a particular effort to promote “connectivity through Myanmar and Thailand with other ASEAN states.”

However, given its emphasis on regional autonomy, India is concerned about “open support for the Indo-Pacific, in particular military commitments to an open and free, rules-based maritime region as it could result in an escalation in Sino-Indo geopolitical tension with China.”

India also countered China’s BRI with the unveiling of “the Asia–Africa Growth Corridor, an India–Japan joint effort to support development in Africa.”

In addition, India promotes its own projects such as ports in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Iran, while enhancing its relations with ASEAN over maritime cooperation and satellite data access and naval training.

At the same time, despite concerns about a rising China, some Indian analysts also highlight the promises of working with China through the BRI.

For instance, proponents of the BRI point to possible economic benefits to India’s domestic infrastructure building, especially “the northeastern part of the country, which has traditionally been geographically distant from the rest of India and from major cross-border trading routes.”

Furthermore, India’s participation in the BRI could help New Delhi “play a leadership role in South Asia’s infrastructure and economic integration.”

More broadly, most Indian foreign policy experts “recognize the need to maintain substantive cooperation with Beijing as leverage for dealing with the West and promoting India’s own development.”

As such, when China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, India quickly joined it and led the BRICS group to “jointly sponsor the New Development Bank headquarters in Shanghai, under an Indian chief executive.”

It is against this complex strategic backdrop that the Trump administration unveiled the FOIP with India as a major counterpart.

The 2017 US National Security Strategy document welcomes India’s rise as “as a leading global power and stronger strategic and defense partner.”

The main reason for this increasing weight given to India is the view of New Delhi as an “important balancing counterweight to China’s rise.”

However, given its emphasis on regional autonomy, India is concerned about “open support for the Indo-Pacific, in particular military commitments to an open and free, rules-based maritime region as it could result in an escalation in Sino-Indo geopolitical tension with China.”

Similarly, New Delhi is not enthusiastic about the Quad grouping—not only because of its relations with Beijing but also because of its fear of being seen as “America’s pawn in power games with China.”

One analyst even calls the Quad a “strategic liability,” as it “would disturb India-China relations and could also prove unfeasible in terms of finances and logistics.”

Instead, India has approached the FOIP mainly as “an extension of its Look East policy in Southeast Asia.”

Indian analysts also raise questions about limited inclusivity in the FOIP. For instance, Jagannath Panda contends that the US regional strategic vision is “based on an anti-China shift in US security strategy,” which is at odds with “India’s vision for a regional order which is inclusive.”

As such, Prime Minister Modi, in his 2018 speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue, included China and Russia as regional partners, while pointedly skipping the US-led Indo-Pacific Business Forum in Washington, attended by Australia and Japan.

The Modi government’s effort to navigate between the Quad grouping and China continues despite Australia’s hope of strengthening ties with India as its “strategic partner” in light of a rising China.

In addition, India has “not agreed to the elevation of Quad talks to Secretary-level consultations.”

As a consequence, going beyond the US version of the FOIP, India has highlighted a “Free, Open and Inclusive Indo-Pacific (FOIIP)” policy aimed at taking “a leadership role in the region in partnership with ASEAN, while ‘balancing’ its relations with the US and China.”

After the successful reelection of Prime Minister Modi in 2019, most analysts expect that New Delhi will continue to maintain India’s policies toward Washington and Beijing, reflecting its “multiaxial nature” of foreign policy.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that contrary to the expectations from existing accounts, Japan, South Korea, and India have not balanced against or bandwagoned with China.

Instead, they view China’s BRI and America’s FOIP strategy through domestic political prisms, in particular the goal of enhancing regional autonomy.

For the Chinese, it is worth bearing in mind that Beijing’s proactive regional vision will not be fully realized without taking into consideration the pursuits of autonomy undertaken by Tokyo, Seoul, and New Delhi and meaningfully engaging the three Asian nations as equals, not as weaker counterparts for the BRI.

By examining the domestic debate about the two grand strategies in these three case studies, this paper has shown that these Asian nations have been responding to the regional visions of the United States and China in their own ways, complicating the great powers’ regional plans.

The findings of this paper have broader theoretical and policy implications.

First, in predicting state behavior in the face of rising powers, we need to go beyond structural determinism. Instead of a priori assuming balancing, bandwagoning, or hedging in response to systemic changes, one needs to devote greater attention to the local lenses through which regional power dynamics are gauged and contested.

National reactions to the shifting regional security order cannot be explained by material power considerations alone. More often than not, domestic political considerations, especially the ruling governments’ pursuit of greater regional autonomy, have influenced the ways in which Japan, South Korea, and India understand and cope with the BRI and the FOIP.

As for policy implications, Chinese and US policy makers should be more attentive to the regional perceptions of their grand strategies.

A common assumption in US policy circles that an increasingly assertive China would automatically compel Asian states to join a US-led balancing coalition is misguided.

In fact, there have been growing questions about the US role in the region. Cases in point are the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the TPP and its confusing messages to its allies over Washington’s diplomatic commitment, including the role and duration of the US military presence in the region.

The limited role of the United States was also shown in its failure to mediate tensions between Seoul and Tokyo over Japan’s trade restrictions on South Korea and the Moon government’s decision not to extend an intelligence-sharing agreement with Japan, known as the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA).

The diplomatic rift in turn has the potential to undermine the FOIP. Worse yet, given the political salience of autonomy, pressuring the Asian allies to join the US campaign to contain China would not only undercut those domestic political actors in support of alliance ties, but it may also embolden domestic actors that seek greater regional autonomy.

For the Chinese, it is worth bearing in mind that Beijing’s proactive regional vision will not be fully realized without taking into consideration the pursuits of autonomy undertaken by Tokyo, Seoul, and New Delhi and meaningfully engaging the three Asian nations as equals, not as weaker counterparts for the BRI.

\More broadly, despite the promises and potential of the BRI and the FOIP, without a fuller understanding of regional perceptions and responses, coalition building will be much harder for both China and the United States, and the resulting regional order in Asia will be far more complex than the extant accounts of hegemony and balancing typically assume.

(Il Hyun Cho is an Associate Professor in the Department of Law and the Asian Studies Program at Lafayette College, US)

(The Air Force Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA) — United States’ Air Force and Khabarhub — Nepal’s popular news portal, have agreed on a sole partnership to disseminate JIPA research-based articles from Nepal. This article appears courtesy of Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs and may be found in its original form here https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA)

Comment